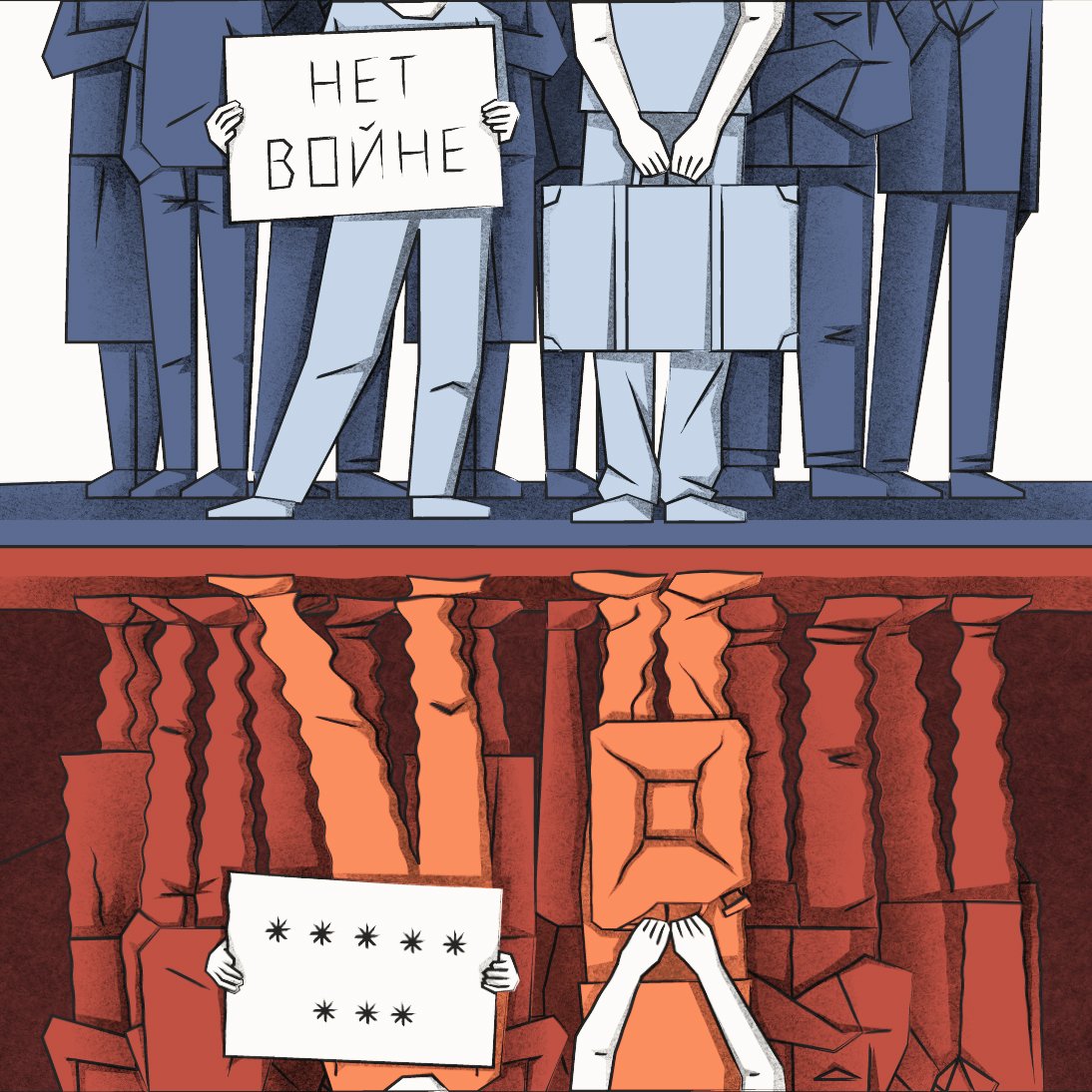

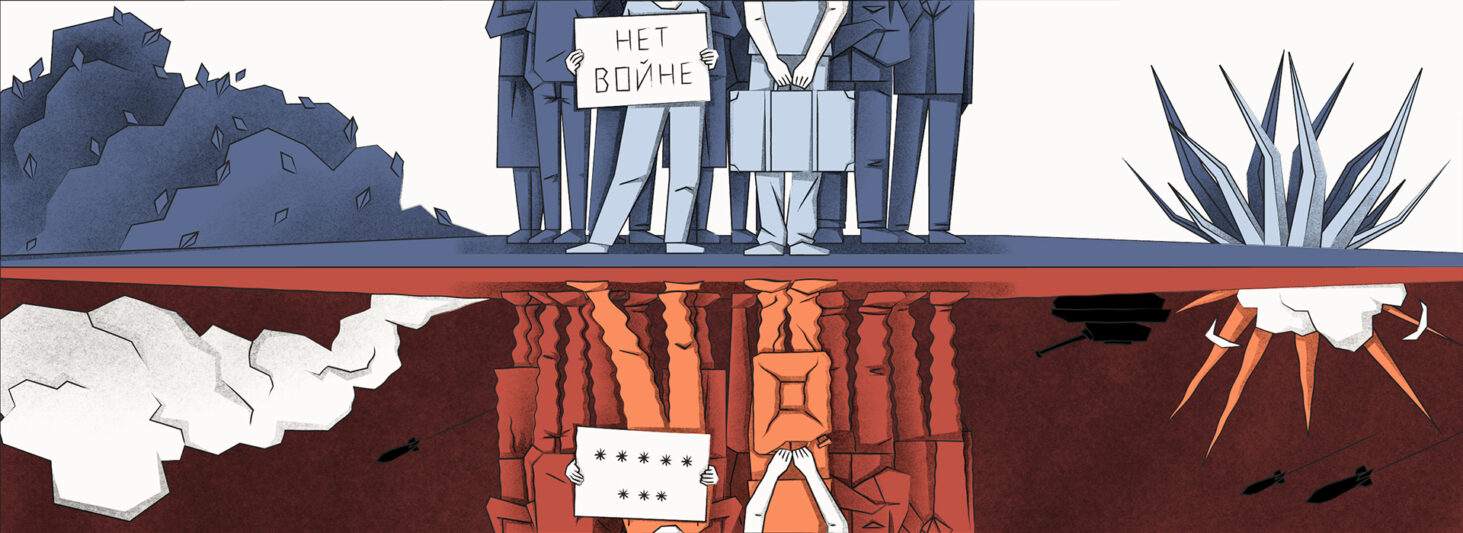

The words ‘Russian’ and ‘activist’ are not frequently seen together in the English-language press, unless to identify those imprisoned, forced into exile, or worse.

But Russian activists do exist, and not simply as victims of state repression.

Indeed, a complex web of anti-war, feminist, environmental and social justice campaigners have been active throughout Putin’s 23-year rule, with a variety of tactics at their disposal, from demonstrations to direct action. The ongoing war in Ukraine and subsequent state crackdown on free speech in Russia has forced activists to adapt to a more amorphous, and cruel, political landscape.

But within this huge challenge, there are glimmers of hope in the kind of decentralised, horizontal organising which is being coordinated by those in and outside of the country, in tandem.

The Great Russian Exodus

Though the Ukrainian people have undoubtedly been the greatest victims of Russia’s ongoing war on their nation, the situation for ordinary Russian citizens has also catalysed since the full-scale invasion of February 2022.

The very limited freedoms that Russians have are deteriorating fast. Independent media outlets have been outlawed: being publicly anti-war can lead to 15 years in prison, and even calling the conflict a “war” or “invasion” is essentially illegal.

Many of those most likely to be targets of the regime – young, outspoken activists and journalists – have been pushed out of the country for fear of political prosecution or violence, which can remain a real threat, even with the geographical distance. Plenty have fled to neighbouring countries with cultural ties, or European cities with established or growing Russian diasporas. Georgia, Armenia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Finland, Serbia, Czechia and German cities such as Berlin remain likely destinations.

Various groups were set up in Europe to educate and inform from the perspective of progressive, anti-war Russians. This coalesced around the idea of recent and veteran Russian émigrés using their status as outsiders to the internal political system. They wanted to demonstrate that many of their compatriots are in fact not in step with the state, and have a range of misgivings about the direction of their country.

One example is After Russia, a volunteer-run platform that was formed to encourage cross-country dialogue with Russians and platform anti-war voices. Their website has stories of ordinary Russians in and outside the country, including activists who have faced persecution, and a ‘Russia explained’ section, which details recent Russian political history to provide important context to the ongoing situation.

Its writers do not mince words about Russia’s ultimate culpability for the war:

“The war was started by Russia, almost 10 years ago, and ended up in a massive intervention on 24 February, 2022. There are no grey areas – Russia is to blame…what can be done now? We look for no easy answers, nor do we want to fool our readers with simple solutions. The more opinions and views we gather, the better.”

In this, platforms like After Russia also function as informational resources – archives of opinions from Russophiles and the Russian diaspora, away from unhelpful stereotypes which can be perpetuated by western commentators.

Ins and outs

The exodus of many Russians has had a profound effect on the state of Russian activism. Part of the work of those that fled has included mobilising and supporting the work of activists still in-country. A symbiosis has developed between those who left to operate more overtly, and those who remained to fight covertly from within.

Activists who have settled in less restrictive environments have the advantage of access to more resources, and the chance for greater cooperation with foreign allies and international activists. They have been filtering this back into Russia, bypassing the tightly controlled media, to plan and assist actions in-country.

Feminist Anti-War Resistance (FAR) is a grassroots, horizontally structured activist group which operates both in and outside of Russia. Created the day after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine by uniting many feminist activists and groups, its original function was to help coordinate the flurry of anti-war protests which erupted across Russian cities in the days and weeks that followed, alongside other oppositional movements.

I spoke to one of FAR’s organisers Lölja Nordic, a Russian eco-feminist, anarchist, artist and DJ. Born and raised in St. Petersburg, her early activism involved taking part in liberal oppositional rallies, but she quickly realised these structures had toxic dynamics, gender inequality and discrimination within their own ranks. Instead, she started joining local feminist groups, self-educating, discussing radical texts with other activists, and organising more inclusively. This would lead to her being targeted for harassment by the authorities and eventually forced to leave the country.

“In 2021, there was an intense shift in the repression I was facing for organising and taking part in rallies and protests,” she begins. “I was arrested four times within a year and a half before leaving Russia. It escalated after the full-scale invasion – the authorities started a terrorism case against me which was fully fabricated. The special police squad raided me – they broke into my apartment with automatic guns, made a mess and arrested me as a terrorist suspect.”

This show of violence and force from the Russian police is sadly not uncommon – sometimes even escalating to the physical abuse of detained protestors.

“They didn’t find any evidence to convict me within 48 hours, so had to free me. Some laws in Russia still work, even now,” Lölja adds wryly.

“When I was released, I hid in a secret apartment for a day. With help from international activists and NGOs, I was able to get an emergency visa for Estonia. Since then, I have not been able to return to Russia. I think I would get arrested almost immediately.”

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

In the chaos that followed the invasion, many activists and protestors were either arrested en masse or forced to flee like Lölja. It was becoming apparent that FAR’s initial tactic of agitating for street actions had to evolve.

“Peaceful protest doesn’t work in authoritarian regimes where police have all the freedom to beat the shit out of you, rape, murder or torture you,” she says. “The amount of police in Russia is insane. It is impossible for unarmed, inexperienced people to fight soldiers trained for years specifically to put down grassroots oppositional protests. We basically have a regular army inside the country – the only purpose of this police force is to block any protest activity.”

“It felt impossible. Thousands of people got arrested, and others faced police brutality, violence or torture. We realised it was not sustainable anymore: the protests had to transform into something more anonymous and partisan.”

The crackdown on protest from the state prompted the anti-war movement to begin to take more covert forms.

Under the cover of darkness

As the war dragged on, underground actions became more dominant and widespread. It helped that FAR was spreading to many cities with Russian diasporas and freshly arrived anti-war activists. Its approach became both on and offline, in and out of Russia.

Like other Russian activist groups, FAR began focusing on the informational war, reaching citizens beyond the narrative of state propaganda to agitate anti-war sentiments. Popular methods included the mass writing of anti-war messages on Russian banknotes, supermarket labels, graffiti, and even targeting viral memes and WhatsApp greeting cards, shared by teenagers and babushkas alike. This had the intended effect of educating misinformed or apathetic Russians with facts about the true nature and brutality of the war, including the real number of Russian casualties – something the state tends to downplay or refuse to acknowledge.

FAR have attempted to slow down the mobilisation of new Russian army trainees by teaching people how to escape recruitment or recall relatives back home from the front. There are hotlines and Telegram bots to contact lawyers and NGOs who specialise in resisting mobilisation, but most civilians are simply unaware these options exist.

FAR have also been publishing their own Russian newspaper, with a twist. Titled Women’s Truth, it is designed to imitate the free local newspapers found in neighbourhoods across Russia, so as not to gain the attention of the authorities. Only instead of light entertainment, its pages are filled with radical anti-war and feminist content. The newspaper is freely available online as a PDF, and Russian activists in-county are encouraged to print it at home themselves to distribute locally in a safe manner, usually at night, on university campuses, libraries, in parks or other public spaces.

Lölja’s account of this newspaper’s dissemination was encouraging: “We received feedback that Women’s Truth was spread in almost 100 cities across Russia.”

A distribution of radical literature across Russia’s vast land is no small feat given the current political climate, and demonstrates the hunger that exists to educate and oppose the war, without many more livelihoods being sacrificed needlessly.

Beyond the informational war

Another key part of FAR’s activism has been supporting displaced Ukrainians. Millions of Ukrainians who found themselves in occupied territories have been transferred to Russia, without being given a choice to leave to the Ukrainian side. Lölja explains to me that authorities tend to spread these Ukrainians across Russia, not grouping them in case it leads to people mobilising or organising. Many were placed in terrible conditions without being given another option.

Lölja tells me how activists and ordinary Russian citizens began to build an underground mutual aid network to support displaced Ukrainians. FAR works with volunteers on the ground who help these forced refugees that have often lost everything and may even be wounded. Humanitarian aid has been arranged for recent arrivals in Russian towns and villages, and assistance given to allow Ukrainians to leave more remote areas safely, and even the country.

“Most try to first get to Moscow or St. Petersburg somehow, then to nearby borders,” Lölja explains. “Estonia is one of the most popular routes. After escaping Russia, I joined the local grassroots refugee initiative in Tallinn. I took shifts at a bus station to provide help for new arrivals who did not know what to do next.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, many deported Ukrainians desired to return to their home country, even with the current dangers.

“A lot of people I worked with had made this terrible journey across Russia but still felt more comfortable to go to western parts of Ukraine rather than become a refugee elsewhere. We heard terrible stories of Europeans mistreating and abusing Ukrainian refugees. At FAR we also raised awareness of human trafficking – any war is a magnet for exploiters. Many Ukrainian refugees fell victim to this.”

Indeed, human traffickers have a sordid history of taking advantage of populations that face escalated social and economic pressures due to conflict. The situation that Russia has enacted in Ukraine tragically follows the same patterns. Trafficking can even end up functioning as a weapon of war, where those that are ‘othered’ are punished and exploited, as was observed in the Second Sudanese Civil War.

In addition to refugee support, some Russian groups have also been taking more direct action in-country to resist the war machine.

Significantly, the Stop the Wagons (STW) movement has been working to slow down the rail transportation of military equipment, weapons, ammunition and fuel to the front – in both Russia and neighbouring ally Belarus. The work of these ‘rail partisans’ has included acts of sabotage – dismantling and destroying rail lines so freights cannot pass.

All activists partaking in these actions remain strictly anonymous, not even taking photos of the trains they’ve overturned. Before their Telegram channel was blocked, it was approaching 3,000 subscribers, and contained detailed instructions on how to safely sabotage trains without hurting anyone. They had also posted a map showcasing successful railway resistance actions covering 30% of the territory of Russia, and coordinated by at least 20 direct action groups.

Other forms of direct action from a variety of activist networks have included throwing Molotov cocktails at Russian military conscription offices, setting them alight to physically, if temporarily, prevent the recruitment of new soldiers for the war. These actions are mostly done by anarchists and on weekends or at night where no staff are present – the aim is not terror, but to obstruct the recruitment process, which is a substantial way that Russia continues its war, particularly targeting its poorest regions.

Always safety first

All these tactics have culminated in a multi-faceted protest movement against Putin’s war, where brave anti-war Russians still under his thumb are supported by a more flexible outside network. This has created a unique situation for organising in one of the hardest countries to do so.

Political action in Russia has been difficult for decades, but the new era of censorship and repression that Putin has pursued since 2022 has meant activist safety protocols are vital – even life-saving. As an example of the measures that need to be taken, FAR have specific systems to verify those joining their groups in Russia, and all contact is made using decentralised communication networks. Crucially, it is forbidden to de-anonymise oneself.

“No-one uses their real name or shows their face,” Lölja explains. “The whole system of communication is built up with different levels of access to certain sensitive information, using different names. One person may have multiple aliases if they work across different working groups. It is another tool to make it less easy for the Russian FSB to intercept.”

Lölja also explains that it is necessary for FAR and other activist groups to emphasise how to take action safely, since doing anything anti-war has become so much more dangerous. Precautions that seasoned activists may take for granted – such as hiding one’s face at demonstrations or practising digital security – needed to be articulated to people who were radicalised by the war but not previously active. Thus, a more sustainable and less impulsive approach to taking action has developed, stressing safety protocols which can help swathes of people to remain free, and therefore active, for as long as possible.

Resistance takes many forms

The way Russian activism has morphed and shaped itself in such a short time shows the resilience of many anti-war Russians and their commitment to taking action. But they have to do it smartly, and safely – which can be psychologically draining.

It is complacent to assume all Russians are pro-war – just because anti-war protests are not seen on the scale they have been before, it does not mean resistance is not happening. It is in the underground, it is being discussed in encrypted chats under aliases right now. It lives.

“When FAR started, we were only thinking about street protests,” Lölja tells me. “Now, a year and a half later, we are a bigger movement, a network of working groups with very specific aims. Agitation is one, supporting refugees another, as are helping political prisoners and activists who need to self-exile because their lives are in danger. We advocate for those who can’t be as public as me and speak for themselves because they are in Russia.”

She continues: “We as a movement are trying to build dialogues with other political initiatives, but we also have criticisms of liberal Russian opposition groups. We try to call them out and raise some issues about making them more inclusive. But our priority as FAR is to use our platform to raise the voices of those who have less possibilities than we do. This includes supporting the decolonial movements in Russia, where Indigenous communities and people from different national republics are fighting, not only against the war but for independence and the preservation of their identity, language and culture. These people are the future of Russia.”

Though organising against the Russian war machine and other injustices has huge challenges, its future is not as bleak as one might think. Perceptions and circumstances change. Putin’s stability as a leader has seemed less certain than ever in recent months.

The creativity and variety of tactics practised by Russian activists, adapting to massive restrictions on their ability to organise and even being pushed out of their country, signals a steadfast willingness to fight – even in the most dire of circumstances. The input of exiled Russians, working alongside anonymous disruptors in-country, provides a ray of light to an otherwise grey forecast of war, and serves as a useful lesson on flexibility to activists worldwide.

As Lölja puts it, “Our work is only possible because we have activists, organisers and coordinators currently in Russia and not able or willing to flee, and those of us in exile like me. Anti-war resistance in Russia needs people inside and outside the country working very closely together.”

What can you do?

- Support independent Russian media:

- Support activist initiatives and independent NGOs in Russia

-

-

- Зона Солидарности (Solidarity Zone) – Russian activist project providing help for political prisoners in Russia.

- Вывожук (Vivozhuk) – grassroot initiative helping with emergency evacuation to Russian activists in danger and political prisoners.

- Идите Лесом (Go by the forest) – initiative that helps Russian citizens escape mobilisation and conscription.

- Movement of Conscientious Objectors to Military Service in Russia.

- Center T – legal and psychological help for transgender people in Russia

- Internationally, support Квiр Свiт (Queer Svit) – a Black queer-run independent team of volunteers from all over the world helping LGBTQ+ and BAME people affected by the war in Ukraine and/or political repressions get to safety by providing consultations, purchasing tickets, finding free accommodation and providing humanitarian aid.

-

-

- Sign this petition for abortion rights in Russia, started by Feminist Anti-War Resistance

- Watch YouTube channel 1420 by Daniil Orain, to hear the opinions of ordinary Russians being interviewed on the streets of Moscow and other cities about ‘controversial’ subjects to speak out about, like the war and press freedom

- Ask a Russian a question on the After Russia platform

- Read personal stories of Russians and Ukrainians since the invasion on the platform ochevidcy 24/04/2022

- Read ‘How the Indigenous people of Russia are reclaiming their land and the climate narrative’

- Spread the word that Russian activists do exist – just because we don’t see protests taking place on the streets of Moscow, it does not mean other forms of resistance are not happening.

- Other related articles on shado: