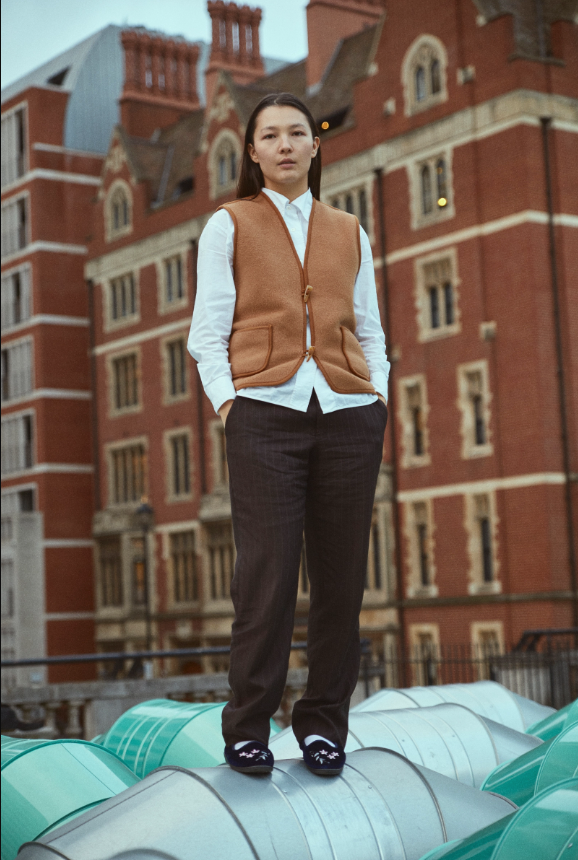

A wonderfully talented musician with mixed Mongolian and French heritage, Céline Dessberg writes songs that touch the soul, connecting with listeners through her own emotional vulnerability.

At the end of last year, I had the opportunity to meet with Céline after her very first live show in London – an evening which also served as a powerful display of solidarity with Palestine. I recall the strong emotions I felt during her performance, and the effect that her music had on the audience. Céline’s emotional vulnerability created a powerful sense of togetherness between everyone, in a way that connected us to the events and people beyond the space.

Over cups of tea a few weeks later, we spoke about Céline’s journey into rediscovering her identity through music, and why she particularly feels a strong sense of involvement in the decades-long plight of Palestinian people and their cultural erasure.

Childhood and musical beginnings

Céline was born in the French countryside, growing up in a forest environment where she spent her time surrounded by greenery and playing in the trees. This closeness to nature during her childhood instilled a sense of Mongolian identity early on, and she recalls her mother bundled her up in covers – “like a real Mongolian baby!” she laughs, describing the way babies are traditionally wrapped up in layers of blankets to stay warm in the harsh climate.

I was fascinated to learn about what Céline describes as the ‘blue stain’, also known as slate grey nevus – the distinctive birthmark prevalent among the people in the central Asian region, which appears on one’s lower back at birth, but later fades over the years. Céline was born with this stain, and sees it as a physical marker of her Mongolian identity.

Moving from her house in the countryside to an apartment in the city was a difficult transition, facing discrimination from her peers and feeling the pressure more and more to assimilate with her French surroundings.

“The town where I grew up was not diverse nor open minded, and as a result I started ‘killing’ the Mongolian side of me,” Céline explains. “My Dad is French, so I tried to become ‘more French,’ not responding to my mother when she spoke to me in Mongolian.” She continues: “I felt the social pressure to be like everybody else.”

As a fellow child of mixed parentage who grew up moving around, I deeply resonate with Céline’s story in negotiating heritage and cultural identity. Although I am lucky to not have experienced as much anti-Asian racism, my upbringing in different countries sometimes left me feeling rootless, and forced to constantly assimilate to my surroundings in order to feel like I belong in a community.

Music appeared as a solace to Céline in her teenage years, picking up the guitar first and beginning to write songs at around age 13. However, not seeing any other Mongolian singer-songwriters in the western media, she found it hard to imagine that she herself could follow a career in music.

“I was studying to get a ‘normal’ job in an office, which was what I thought I was meant to do. Like, I thought I was going to be a judge!” Céline grins, making the gesture of a judge hitting the bar.

While studying, Céline continued to create music, and eventually realised that this was what she was meant to do. “It’s the only thing I can be a perfectionist about!” she explains. “I didn’t really care about anything else.”

Céline also tells me that, since pursuing music professionally, her eczema which was caused by stress from her intense studies has healed. Music has spiritually and physically served as a healing source for Céline, and now she is working to pass this power on to others.

Reconnecting with Mongolian identity through music

In 2020, around the same time that Céline started pursuing music full time, she received a yatga (Mongolian harp) from her family. The instrument is a variant of the Box zither, whose body is a long wooden box, the performer plucking the strings with the fingernails of the right hand while the left hand puts pressure on the strings to change the pitch of the note, producing soft delicate sounds.

“It was the best present ever!” Céline says, explaining how this gift allowed her to grow closer to this side of her musical heritage. In combining her playing technique for guitar with traditional teachings of the yatga, she was able to use music to “mix her two cultures” – which she’d previously tried to separate.

In Céline’s song ‘Yatqa’ from her first EP DO NOTHING, the ‘Eastern sounding’ pentatonic tuning of the instrument is combined with the western picking technique on guitar, accompanying her lyrics in English.

She describes this song as an “ode to the planet,” inspired by traditional long song Mongolian style of singing, in which each syllable is extended over multiple notes. Through her skillful vocal movement techniques, the music blurs physical and metaphysical boundaries, and the individual words evoke a sense of loss in an increasingly grey urban landscape, with the opening lines, ‘Glass, concrete and stone, that’s what our city is made of.’

The song raises awareness of the loss of nature and wildlife, and makes me think about the other forms of natural and cultural erasure in Indigenous lands in Mongolia and other parts of the world. I think about the transition she must have faced when moving from the French countryside to the urban suburbs, and seeing much less of the beauty of the natural world that she had been used to growing up. With her soft piano arpeggiated patterns, melancholy reverb of plucked guitar combined with the distinct sound of the yatga, I feel a sense of this struggle, and connect with the story shared by Céline.

In particular, reconnecting to cultural heritage in tangible ways through musical instruments is something I relate to deeply. I am reminded of my own Japanese grandmother, who taught me how to play the shamisen – a three-stringed Japanese instrument which is plucked using a spiked paddle called a bachi.

The shamisen is traditionally played by the Geisha – a class of female entertainers and the profession of my great grandmother. I remember feeling an overwhelming sense of connection with my grandmother, as well as to my Japanese roots, through these simple acts of practice and sharing intergenerational musical and cultural knowledge passed down from my family.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

In addition to the incorporation of the Yatga in her music, Céline found that marketing her identity as an artist indirectly aided her journey into embracing this Mongolian heritage.

“As an artist, your image is so much of your brand,” Céline says – particularly when you’re emerging in a Western musical circuit. She explains that if Mongolian ‘appearances’ can be harnessed on the artist’s terms, rather than for the onlooker’s gaze and profit, it can be a powerful tool to raise awareness and increase representation of Mongolia to wider audiences.

Céline tells me how she was naturally drawn to the “delicate, beautifully patterned and colourful” Mongolian clothes. I remember being captivated by her outfit at the concert, the traditional designs and colours leaving a lasting impression. This presentation seemed like the perfect way to set herself and her music apart from others, and share the beauty of Mongolia to the world.

“Nowadays it’s become my aim to become a channel for people in Europe to discover how rich this culture is,”Céline explains.

She’s drawn to music that makes her feel, and she wishes to communicate this feeling to others through her own songs, without being too restricted by a specific genre or category. Céline’s songwriting transcends language and cultural barriers, to travel directly to the heart of the listener.

Connection and disconnection: ancestral identity and negotiating family ties

One of the unreleased songs Céline performed for us at her London show was written about her Mongolian grandparents. As she explains the story of this song, it taps into emotions we both share. Entitled ‘өвөө эмээ (övöö emee)’, translating to Grandfather, Grandmother, the song describes how similar yet different their lives would have been from hers today.

Written simply for piano, voice, and double bass, the stripped back feel contributes to a sense of fragility and tenderness, and Céline explains that writing this song as well as others from her new unreleased album was a vulnerable and painful process. She tells me how difficult it had been to sing the song to her mother for the first time. “I had to dig deep into my memories, my ancestors, genes, in my body,” she explains.

The lyrics of the song describe Céline’s experience seeing her reflection in the mirror and imagining her grandfather’s facial resemblance. “Maybe we have the same skin, maybe the same laugh,” she ponders. “It feels so weird to be so close to someone yet be so spatially and temporally far away.”

Céline describes how her grandmother had always said she was his reincarnation, revealing a dream she had after his passing, before Céline’s birth. “‘She saw a girl from the west with long hair that was dancing and singing, and she saw me growing up, and that was exactly the kid that I was’”. In a way, Céline’s artistry is keeping her grandfather’s memory alive, sharing this heritage and his essence for audiences around the world in her music.

As we talk about this song, Céline starts to get emotional, and I find myself blinking back tears also, remembering my own Japanese grandparents and how much I miss them. I recall how I felt during her live performance, which showed me the power of emotional vulnerability in building connection and solidarity between people through musical practice. After all, thinking about someone we hold dear as a part of ourselves reminds us of who we are, as well as our responsibility to each other. After we collected ourselves again, it was amusing to find out that we were both Pisces star signs.

Divided opinions within families, and renegotiation of political self

Although her music is an opportunity to create bonds and reconnect with her family and heritage, Céline tells me about how her artistic decisions can also result in having to renegotiate family allegiances, as well as an element of sacrifice.

Referring to her gig which I attended, Céline explains that she “just wanted to talk about peace,” but it was hard for some family members to accept her decision to partake in the event. The show was intended to show solidarity with the Palestinian people to call for a permanent ceasefire to stop the genocide in Gaza.

In addition to the disgust towards the terrible atrocities committed by Israel, Céline feels heavily involved in this struggle against cultural erasure. She explains, “when people just kill, they don’t just kill bodies, they kill culture, they kill music, they kill a way of thinking, and it has already happened so many times.”

Throughout its history to the present day, Mongolia has faced multiple forces that have threatened cultural identity, from tackling modernity and urbanisation, to the oppressive periods of influence under the Russian empire, Soviet Union, and Imperial and Communist China. Tragic events in Mongolian history such as the 1930s purges under the Stalinist political model, in which 30,000 people were estimated to have been killed, underscore a sense of struggle in the face of attempted assimilation, reduction of the population, and restriction of language, culture, tradition, history, religion and ethnic identity.

“Mongolian culture is in danger,” explains Céline. Since 2020, the Chinese Government-implemented Language Campaign has restricted schools in Inner Mongolia from speaking Mongolian, with books written in Mongolian being taken off shelves, to promote the Chinese language and create a unified national identity under the Communist Party. To this Céline can relate in a sense, as she stopped speaking Mongolian when she was in France.

Although describing the very real repercussions of such moral divisions within one’s family, Céline explains the importance in staying true to her beliefs, and continues to stand in solidarity with Palestine’s struggle for freedom. These values also cross borders, and Céline believes “it’s natural to show solidarity with this from any region in the world.”

A connection to ourselves

As our interview comes to a close, I ask Céline about what she hopes to achieve with her music. After some thought, she responds: “I would love to let people know more about Mongolia, help people accept themselves, and not feel guilty for the things that they feel.” She continues: “I’m really transparent, I think if people were more earnest with themselves and with other people there would be fewer issues in the world.”

Music is one of the most powerful forces that can shape, and in turn, share one’s identity and human experience to the world in a deeply emotional way. Intensely vulnerable, through her songs, Céline is able to construct her worldview, combining the different facets of her identity through instrumentation, lyrics, and even marketing to express what is most important to her as an individual, such as cultural heritage and family bonds.

As listeners, we can share this experience, and deepen our connection to ourselves, each other, and beyond. In a way, we all have different mixed musical identities, drawing from our own personal stories and experiences. In being open and vulnerable to ourselves, and being exposed to and inspired by different cultures and traditions, as Céline says, we can hope for a more accepting and honest world. I remember how I felt at the gig, and the powerful sense of collective healing shared by the audience of seeing into Céline’s world through her music and vulnerability.

What can you do?

- Listen to Céline’s music

- Follow Céline on her socials

- YouTube: @celinedessberg2068

- Instagram: @celinedessberg

- Read more about Mongolian Heritage and Natural Conservation efforts

- Follow + learn from Palestine Solidarity Campaign