In 1993, the Ogoni people forced Shell to halt their drilling practices in the region of the Niger Delta. This made them the first Indigenous group to go against a British oil company in court and win.

This landmark case forms just part of the six decade fight against continued environmental genocide in the region.

As recently as January 2024, Shell announced its intention to divest from the Niger Delta without any commitment to cleaning up the environmental devastation they have caused. Communities are organising against this, as well as Shell’s focus on deepwater, offshore extraction, continuing to advocate for sovereignty over their land and waters.

So, while the fight for the Niger Delta is far from over, this struggle exists as a powerful resistance movement that organisers and activists around the world can learn and take inspiration from.

Oil in the Niger Delta

“If you’re looking for a definition of ecocide, the impact Shell has had in the Niger Delta clearly defines that crime,” Nnimmo Bassey tells me. He is a leading Nigerian environmental activist, architect and Director of Health of Mother Earth Foundation.

Oil exploration in the Niger Delta began in 1908 during British colonial rule, and in 1956 the first oil well was successfully drilled by Shell. Soon after, other oil companies also began extracting from the region, including Mobil, Elf, Agip and Chevron. It quickly became clear that this would be a disaster for the livelihoods and environments for millions.

In 1888, the Niger Delta was described by colonial administrator Harry Johnston as having “perfectly fresh water”, an “extravagant development of vegetation”, and “every type of foliage in every shade of green.”

Now, this same water is contaminated with the carcinogen Benzene, at levels over 900 times above the World Health Organisation’s guidelines. In fact, every single year for 50 years, the Niger Delta has suffered the equivalent of a major oil spill on the scale of the Exxon Valdez disaster which devastated over a thousand kilometres of the Alaskan coastline.

Health of people and planet

The Niger Delta is a densely populated region in Nigeria, inhabited by 30 million people from 40 different ethnic groups. The implications oil extraction has on all these lives are endless. Gas flares, the burning of unwanted natural gas during crude oil production, fills the air with toxic pollution and has caused acid rain.

“I am one of the victims of Shell. My son has respiratory problems because there is no clean air,” local journalist Tife Owolabi tells me. “Because of Shell, we are all smokers in the Niger Delta, because we are forced to inhale toxic gas flares every day. Everyone is suffering from one ailment or the other.”

The oil spills also result in local people drinking and eating food which has been contaminated by hazardous metals such as chromium, lead and mercury. A 2020 report published in the International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics showed that infant death is 2.16 times higher in the Niger Delta compared to areas in Nigeria where women are not exposed to high levels of oil pollution. “Funerals have become the major festival in the region,” laments Nnimmo. He tells me that the life expectancy in the Niger Delta is just 41 years old, as these oil spills have caused cancer, bronchitis, birth defects and miscarriages.

Speaking with Maimoni Mariere Ubrei-Joe, Climate Justice and Energy Programme Coordinator for Friends of the Earth, teaches me more about the devastation to the Niger Delta’s once booming agricultural and fishing industries. “As we speak, on the coast of Ondo state, the Ororo-1 oil well is burning. Now, just imagine what is happening to the fishing economy in that place,” he says.

With food systems being decimated and farms destroyed, local people are left falling deeper into poverty and food deprivation, which furthers illness and premature death.

This is the wreckage that is left by international oil companies in the Niger Delta. Resisting these powerful companies is a matter of life or death.

Local communities are fighting two sources of power

Though 70% of people in the Niger Delta live below the poverty line, oil has generated $500 billion for Nigeria which accounts for 80% of the government’s revenue. This creates a complex power structure where the people of the Delta are not only resisting transnational oil companies, but also the Nigerian government who benefits greatly from oil.

Such resistance has posed significant risks in the past. This is seen in the extreme lengths that have previously been taken to ensure there is no threat to oil extraction, such as the Nigerian government colluding with Shell to harm and murder environmental activists and local people.

This is the complex consequence of attempting to contend with the money that comes from natural resources; money which also increases cases of theft and illegal extracting activities, adding yet another source of violence and power to contend with.

A 2022 report by Global Witness revealed that environmental activists are killed at a rate of one every other day in countries including Colombia, Brazil, the Philippines and Mexico; they are rarely protected by governments who have already granted colonial impunity to transnational companies. What we see is that violence by the state against environmental activists isn’t limited to one region, but is a widespread issue in various countries in the Global South.

This highlights that the fight for environmental justice and land sovereignty is a connected movement. Communities in Asia, Latin America, and other parts of Africa can take inspiration from the Niger Delta’s struggle and learn how to combat the violence that results from resource exploitation and lack of government intervention. It also encourages bigger conversations on how we can overcome language, cultural and geographic barriers to strengthen a collective movement against states that perpetuate their colonial past.

As Nnimmo explains, “the Niger Delta is an example of the absolute recklessness of corporations who work in tandem with governments against the interests of the people and the environment. This makes the resistance very difficult and, at times, very dangerous.”

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

Six decades of resistance is also indicative of six decades of minimal government intervention. As Maimoni says: “The Nigerian government is also our enemy. Just look at how it took over twenty years for the Petroleum Act to be passed.” This legislation means petroleum belongs to the Nigerian government rather than the oil companies. It additionally penalises oil companies for gas flaring and demands that revenue from the penalties accrued are used for environmental relief in the affected community.

However, there is a debate around the effectiveness of imposing penalties on oil companies for gas flaring. The concern is that if the penalty is not significant enough to impact the companies’ finances, they are likely to continue with gas flaring since it is a cost-effective way to dispose of natural gas. Therefore, unless the penalty costs more than the investment required to capture the gas, oil companies are likely to prioritise profit over environmental damage.

The understanding that their enemies are twofold have caused the people of the Niger Delta to focus on community unity. There are 250 different dialects across the whole of the Niger Delta, yet different ethnic groups have come together despite these differences, recognising that there is an interconnectedness to their struggle and a shared vision of their liberation.

Kenn speaks on this in our interview. “When people unite, organise and resist, people win. People put their passion, dedication and anger together and it became a powerful cannon to shoot down corporate greed and power. Other resistance movements can learn from that.”

Creative resistance

Knowing that the tools of the state cannot be relied on, the people of the Niger Delta employ innovative and courageous means to fight for change.

One of those tools is creativity. Take Ken Saro-Wiwa, one of the most well-known environmental activists from the Niger Delta. He fought against Shell and for the freedom of the Ogoni people until his execution by the Nigerian Government in 1995. Saro-Wiwa believed in the power of writing as a tool for liberation. His poetry often spoke of the environmental degradation experienced by the Ogoni people. In The Call, Saro-Wiwa wrote:

Stunted crops fast decay

Fishes die and float away

Butterflies lose wing and fall

Nature succumbs to the ecological war.

His literary work was read by people in the Niger Delta and around the world. Saro-Wiwa believed his writing had a significant role in the liberation of his people and in 1994, while he was incarcerated and suspected of orchestrating the assassination of four Ogoni chiefs, he wrote a letter to Scottish novelist William Boyd, in which he recognised that his “talents as a writer enable the Ogoni people to confront their tormentors.”

In this we see how, in the Niger Delta’s resistance movement, writing is not merely used for storytelling but as a means to shape the present and the future. Kenn Henshaw, Executive Director of We The People, tells me that writing continues to be viewed in this way. “Above all means, we have used the power of writing to speak truth to power.”

Nnimmo, who is also a poet, also sees his written work as a tool for activism. “Poetry is protest,” he says. “Without poetry, protest would be very, very dull. Poetry is the spoken word during rallies and when you have them written down it becomes even more powerful.”

Poetry beautifies our cries for justice without dampening its meaning. It makes it memorable so that hundreds of thousands of people can shout their cause in unison.

This creative resistance has also manifested in theatre production. Plays such as John Dudafa’s Mangrove in the Desert are performed in community settings and bring the stories of local people to life through dramatisation. This emphasises a sense of solidarity that these experiences and emotions are universal.

Creativity is an accessible and holistic tool that de-emphasises the importance of academia, titles, and privilege in knowing about and combating issues in the world. This is decolonisation in practice. By harnessing the power of creativity, environmentalists in the Niger Delta have been able to ignite the imagination of their communities and inspire them to take action against environmental abuse.

Community knowledge is power

A second tool of resistance is community education. Maimoni speaks to me about this. “Building community power for local people to understand the dynamics around the oil and gas campaigns was important because before, some people thought that oil exploration was necessary,” he explains.

It is community education on the importance of environmental impact monitoring that gave Niger Delta farmers enough evidence to, in 2023, win a 15-year-long court battle brought against Shell for their 2,300 litre oil spill in 2004. Shell was ruled as responsible for damage caused by oil leaks and ordered to pay compensation to the affected farmers.

With the advent of advanced technology, environmental impact monitoring has given way to local journalism. Nnimmo explains to me that, after an oil well blew up at Santa Barbara Wellhead in Nembe, “the whole world became aware of it because someone filmed it from their canoe and posted it on social media.”

Local journalism puts truth telling in the hands of the local people, and this power is harnessed to great effect to further causes all over the world. Community knowledge, in a time of heightened censorship, has never been more important.

Women are key to resistance

As has been proved by climate disasters all over the world, the climate crisis is a feminist issue. As Kenn says: “Men from the Niger Delta have the option to travel to Abuja or leave to look for greener pastures, but women have to stay home and look after the home. They are forced to stay in corrupted environments, environments no longer economically viable.”

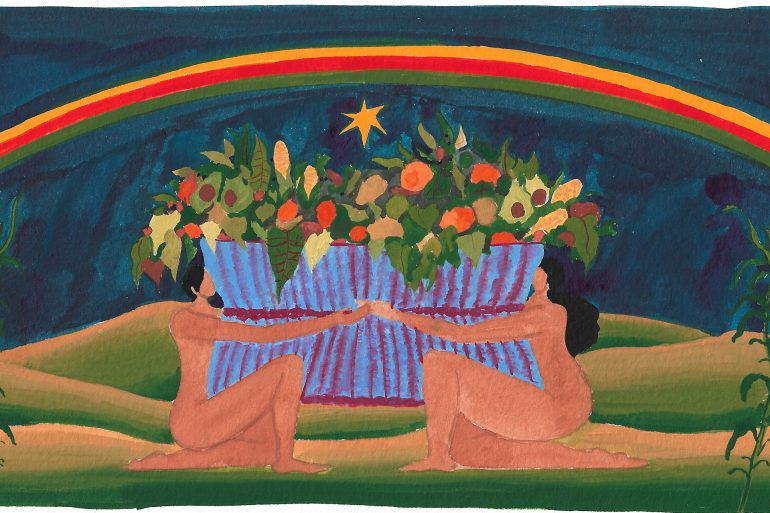

However, feminism also characterises resistance in the Niger Delta. As Kenn says, “women have been instrumental in fighting oil companies. They have used dance, songs, and even nudity.”

One example of this is the action which took place in 2014 in the Peremabiri community in Bayelsa State, where a group of half-nude women protested against workers at a Shell factory. More than just a statement, their undress referenced the ‘curse of nakedness,’ an Indigenous belief that when a woman exposes her nakedness to a man who has angered her, it can cause his ‘social death,’ which in turn can become a physical death. Men therefore didn’t enter the factory to avoid this fate.

Collective vision

From speaking to the environmental activists in the Niger Delta, it’s clear that the tone of our resistance is important. As Nnimmo explains to me, “Organised, non-violent resistance can endure for a long time.” Non-violent resistance is guided by love and seeks to liberate people from oppression in a peaceful way. Nnimmo believes that, in this way, justice is served. “Organising can be dangerous and difficult, it takes a lot of time and resources but in the end, the truth prevails.”

More than tone, resistance movements need to have a clear vision of what justice looks like. As Bassey says: “What do you want to see? What is the future you’re dreaming? Once people collectively embrace that sort of vision and understand it is a destination we’re travelling to, then the inconveniences and harassment will be worth it.”

It is clear that people in the Niger Delta share a collective vision of what environmental justice looks like and that this vision has been the cornerstone of their resistance work. As Tife says: “Environmental justice is not just about compensation: it is about bringing the land back to the way it’s supposed to be, so somebody can go to the water and catch fish like they used to do. It is about people being able to go back to their normal life and the stories their fathers told them about the environment will still be true.” A clear vision facilitates international solidarity among environmental activists, the diaspora, journalists, and many others who are able to spread the common goal.

Despite the prolonged struggle for justice faced by the Niger Delta community, it’s important to recognise the victories that have taken place. These victories signify that change is possible. Transforming the world takes years of inspiring others to first imagine a just future, to then be able to believe that the powerful structures that inhibit such a future can be brought down.

As oil companies like Shell focus on deepwater extraction in Nigeria, it is important to recognise that even this form of extraction poses its own environmental risks. Extracting fossil fuels offshore is not a way to avoid human politics, resistance, and violence. Even deepwater extraction can cause harm to local people. This means that the struggle for environmental justice does not cease when onshore extraction ends or clean ups take place. Environmental justice is fully achieved when oil remains in the ground and exploitative fossil fuel extraction ceases entirely.

Through the Niger Delta, resistance movements can learn that liberation is obtained through daily, organised, community-centred action. That liberation is creative just as much as it is legislative, that it is rooted in the love and desire for the freedom of all people and land. In the words of Saro-Wiwa: “If they do not succeed today, they will succeed tomorrow.”

What can you do?

- Read The Bayelsa State Oil and Environmental Commission to learn more about what oil companies have done to the Niger Delta.

- Read about other battles against oil giants.

- Amplify the voices of environmentalists and organisation on the ground who are working to resist oil extraction in Nigeria. Including: ERAFOEN, Health of Mother Earth Foundation, We The People

- Journalists, writers: Write about what is happening in the Niger Delta so that people in the Global North can learn about the communities impacted by resource extraction.

- Support the Don’t Gas Africa campaign which calls for an end to fossil-fuel-induced energy apartheid in Africa. You can support by signing the petitions on their website!

- Follow and support: Stop Cambo and Fossil Free London to push forward campaigns that seek to end fossil fuels and exploitative resource extraction. Support looks like: volunteering, donating, joining pickets and spreading the word!