Neha Vaddadi is an illustrator and graphic designer based in Hyderabad, India. Inspired by her time spent studying as an architect, Neha’s work focuses largely on the urban, doing immersive sketches for months at a time. She’s fascinated by what makes up a city, and how our city spaces can better serve those who live within them.

We caught up with Neha to discuss how she came to her practice, how she incorporates the issues she cares about into her work, and how she keeps herself inspired in spite of the demoralising state of India and the world at large.

Let’s get straight into it! Your practice seems so unique – what life experiences helped develop it?

Growing up, like countless others, I was a misfit. A frizzy-haired quiet weirdo, a barely-noticeable fly on the wall. But this invisibility allowed me to observe and witness everything with a strange sense of non-attachment. Because there were no eyes on me, I felt completely free to notice and take in everything as it was. I think this observer role is something that continues to shape the work I produce. Whether I am drawing people or places or even myself, it is almost always from this non-attached observer’s point of view.

I think this ties into the very fundamental understanding that we are all the same. Human experiences, although they seem deeply personal to each of us, are actually universal. Our particular contexts and life details might differ, but at the core of it, the sadness you feel is the sadness I feel. My pain, my happiness, my anger, anxieties, are what you feel too. And here is where I think words are limited in scope. Very often, we find ourselves unable to communicate exactly what we feel through words. What interests me is communication that transcends this: the world of feeling and understanding that comes from quiet observation and attention to something beyond oneself.

This seems like such an amazing understanding to reach. How did your journey with drawing first start?

As a child I was sent for ‘drawing classes’ (a common trend amongst many urban Indian parents, at least in the 90s) which bored me to death, quite honestly. The drudgery of having to draw a jug or a bowl of fruit over and over wasn’t exciting to me at all.

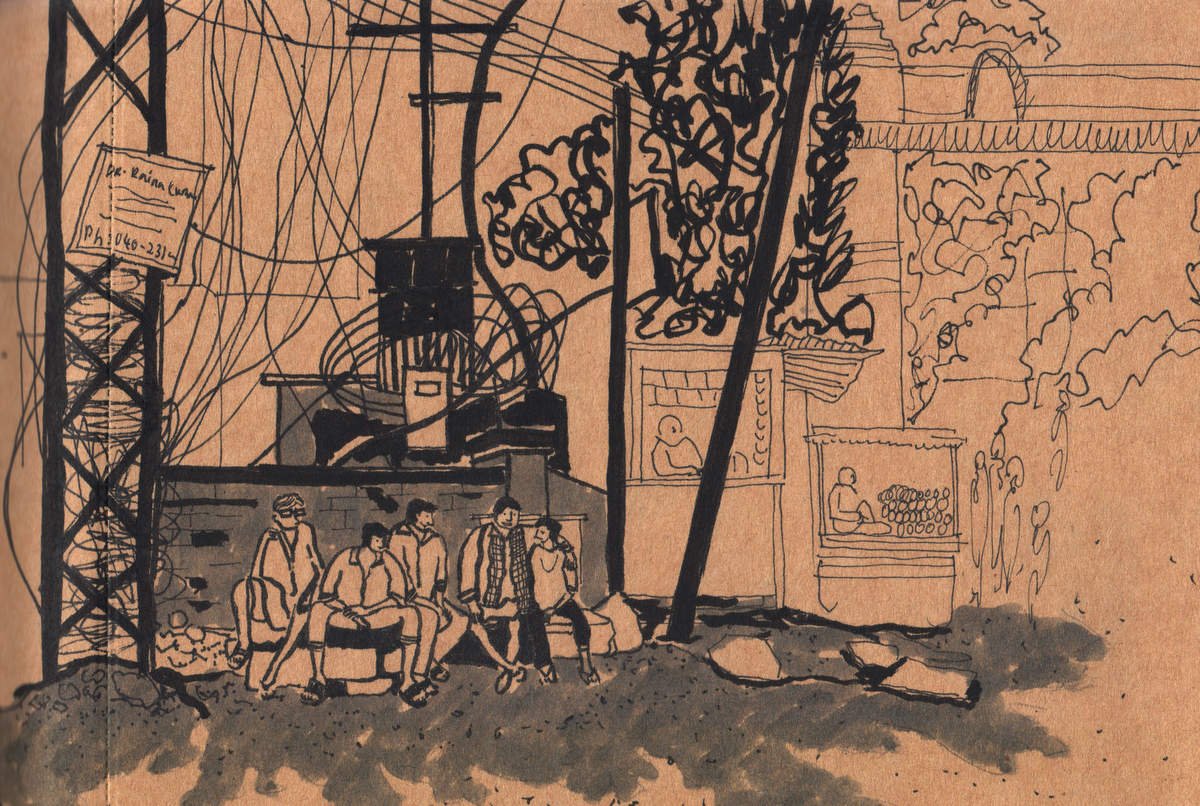

I think it was through architecture school that I started to take to drawing, probably because we were trained to draft all our architectural drawings in studio class by hand. Most people in my class soon migrated to digital software such as AutoCAD, but I found myself sticking to the traditional way. There was a sense of calm in drawing really crisp, precise lines of varied thicknesses or in filling large expanses of white with inky black or in stippling the sheet in an endless sea of dots… come to think of it, this is probably the reason behind my tendency to keep gravitating towards pen and ink/black and white.

It’s so interesting to hear about how architecture informed your practice. Do you think this is also why you’re so interested in urban settings?

So, it’s partly due to studying architecture and partly because I’ve lived in cities for major portions of my life. I’ve had an unrealistic urge to leave everything behind and move to a forest, like so many of us would like to, but subconsciously an optimism concerning my urban environments has held me back, the feeling that somehow all is not lost and that something beautifully nurturing could yet be done with our cities.

I would also attribute the prevalence of cities in my work to the time I spent working at Hyderabad Urban Lab. Working there jolted me awake to this urban reality; I learnt to see how interconnected everything is, to see this pulsating web of networks that form our cities. It was like a series of ‘a-ha’ moments; something one can never unsee, and it continues to inspire me.

What are some of the other subjects and issues that you’re keen to incorporate into your work?

I don’t think I could single out a few issues in particular but anything that is disruptive to humanity in general is something that will always always have my attention. It is deeply disturbing to come to terms with the kind of world we have created as an outcome of the kind of people we are. From seemingly subtle imbalances, like many cities in the so-called ‘developing’ world not having the infrastructure for ordinary people to take breaks, to something larger such as the migrant exodus that happened in India because of the first COVID-19 lockdown. I’ve tried to encapsulate both of these issues in two separate series, ‘Urban Break’ and ‘Migrant Series’, but the list of issues and outrage is endless.

I think when I draw something centered around issues such as these, it’s first important to look at it, without turning away, and try to fully come to grips with the reality of the matter and experience the pain of the subject. Then, I hope that feeling translates and makes other viewers and observers understand the depth of the reality that these drawings are trying to capture, even for a short time.

Can you tell us a bit more about ‘A place for her’, the gender-based project which you have worked on?

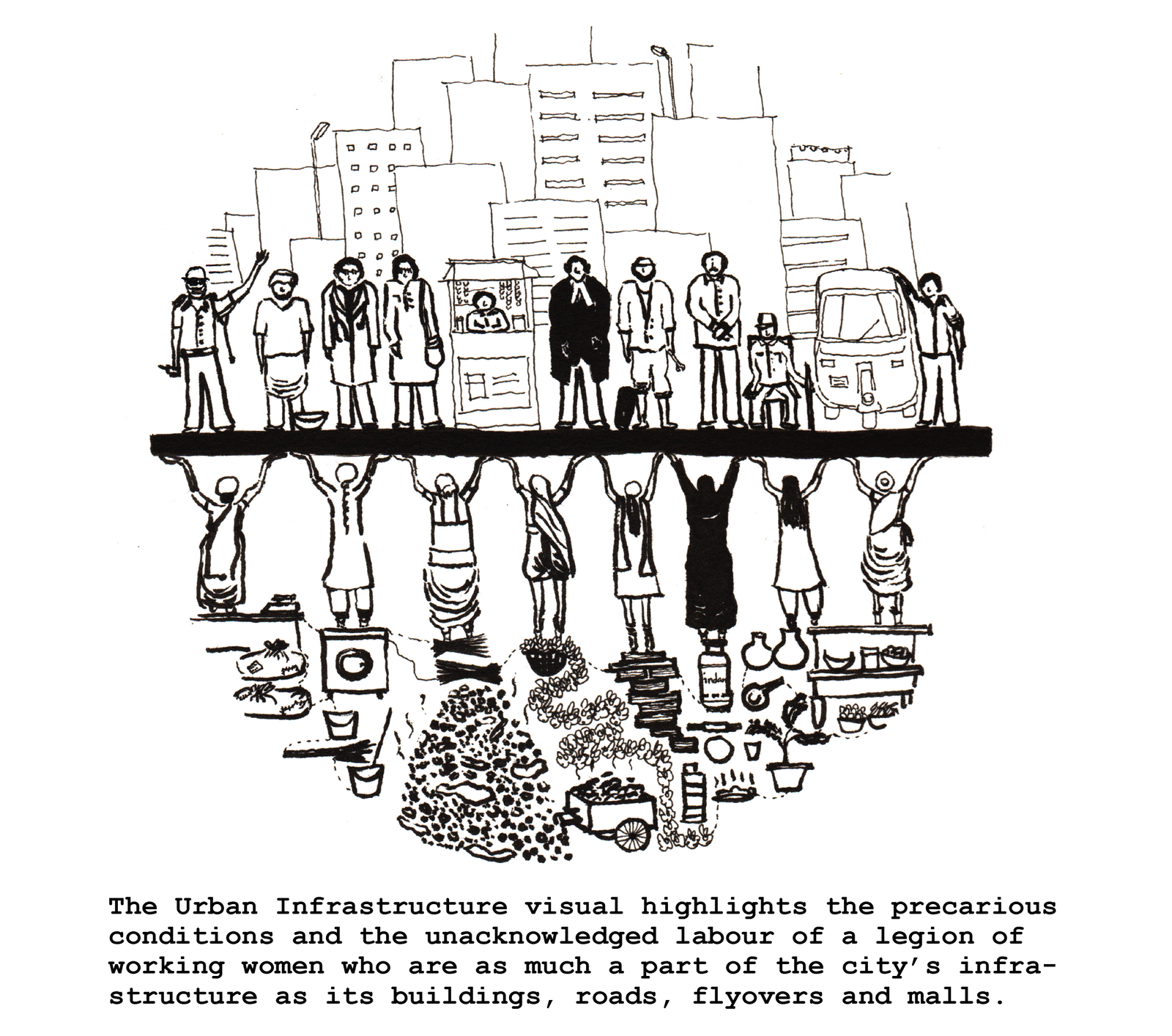

‘A place for her’ is a project started by Hyderabad Urban Lab to explore the role of women in city infrastructure. It has since grown into a physical space for the women of Hyderabad.

The project required us to speak to a lot of women from different backgrounds and ages – many of them constituted the ‘informal’ economy – to understand their place in the urban. The fact that women do a hell of a lot more work than men became instantly visible.

Outwardly it is as though cities are built only by men; men do the important running around, call the shots and make the important decisions. But on taking a closer look it becomes apparent that women are actually working round the clock with far fewer privileges and resources. Without women, men wouldn’t be able to do what they do. I mean, without women, men wouldn’t even be around to begin with! Basic biology.

We are well into the third millennium and it’s none the easier to be a woman. But despite the odds, women are claiming their space and just doing what they must. In Hyderabad for example, there are a multitude of women from lower income groups who have set up make-shift eating joints on the streets throughout the day. They serve home cooked meals and set themselves up on the sidewalk. It’s not easy to manage a business on busy Indian roads and streets. There are constant disturbances and regular harassment from local goons, police, random pedestrians and even some customers. And since it’s completely informal/unregistered, their place on the street is also subject to change. For any individual to be able to handle all of this on their own can’t be easy, let alone a woman who is also expected to run a household. But they’re doing it! They’re figuring it out, navigating the space and staying firmly rooted.

That’s a great story, thanks for sharing. Lastly, what else is exciting you in your community, particularly creatively?

To be completely honest, given the current state of the world and India, it is a bit hard to be truly excited about anything at the moment, as morbid as that sounds. It’s been a difficult few years for everyone, both individually and as a collective. All the systems that we are forced to live in and depend on are facing serious breakdown and people’s freedom of expression is being threatened.

But, despite this, it is encouraging to see people, especially creatives, continuing to express themselves, collaborating with each other and most importantly, making decisions with wellbeing as a priority, both physical and emotional. This pandemic in India has left a lot of people feeling terribly isolated, anxious, depressed and completely unsure of what to expect. I draw hope from the fact that many people who I know are slowing down, taking care of themselves and drawing strength from resting which will in turn fuel creative work and prepare us for what is to come next.

If I had to be excited by something, it is that we still have the wherewithal to keep creating and push through, putting work out there, despite the darkness. So more power to those resting, taking care of themselves, continuing to explore and express, and silently standing their ground!

Keep in touch with Neha’s work on her Instagram