Ronke and BOC’s household is what we would describe as largely patriarchal. We, their children, experienced the displays of masculinity among Nigerian men that positioned our father (BOC) as head of the family, the final say and the wielder of power. We also witnessed the imposed perceptions and understandings of subservience towards our mother (Ronke).

Of course, we recognise how the colonial project obfuscates Yoruba gender dynamics and affects how we see ourselves in this time and space. Nonetheless, BOC sees Yoruba culture through a binary and patriarchal system where, as he says: “men will always behave like men, and women will always expect the men to behave like men.”

As Ronke recalls, “When we were dating, and when we just got married, he used to say, ‘you are the wife, and this is your place to be with the children, and this is my place as a husband.’”

For BOC, this meant that “if you want to eat, you will see that it is your wife that is supposed to cook and bring you food. It has been like that. The woman will be in the house and the man will go out to work. When the man comes, she prepares food for him, he eats and sleeps.”

Notwithstanding, this dynamic did not always go down well.

BOC mentions that there was a time he felt like Ronke challenged his ideas of her role. These often played out simply as Ronke directly expressing her dissatisfaction with BOC’s views, or indirectly, as Ronke taking up prominent leadership positions in government that BOC felt took away from her duties as the ‘wife’.

He believes these allowed them to grow to understand each other in all that complexity. As he describes it, “We’ve been together almost 40 years. So you should know that kind of relationship is solid. Although, you can’t rule out a few misunderstandings, but we have grown to learn how we sort it.”

In The Will to Change, bell hooks highlights how patriarchy often forces men to understand their identities based on the power they hold. When BOC says, “men will always behave like men,” and attaches this to a clear expression of power, the identity of being a man is tied to the ability to wield that power. Often, this power breeds the terms of masculinity that dominate, subjugate and oppress women and queer people. It creates men who do not know how to love or receive love, and frankly, no one wants to love.

Creating loving men

According to hooks, “to create loving men, we must love males.” However, what does this mean in a politicised society where gender plays a massive part in how we hierarchise ourselves?

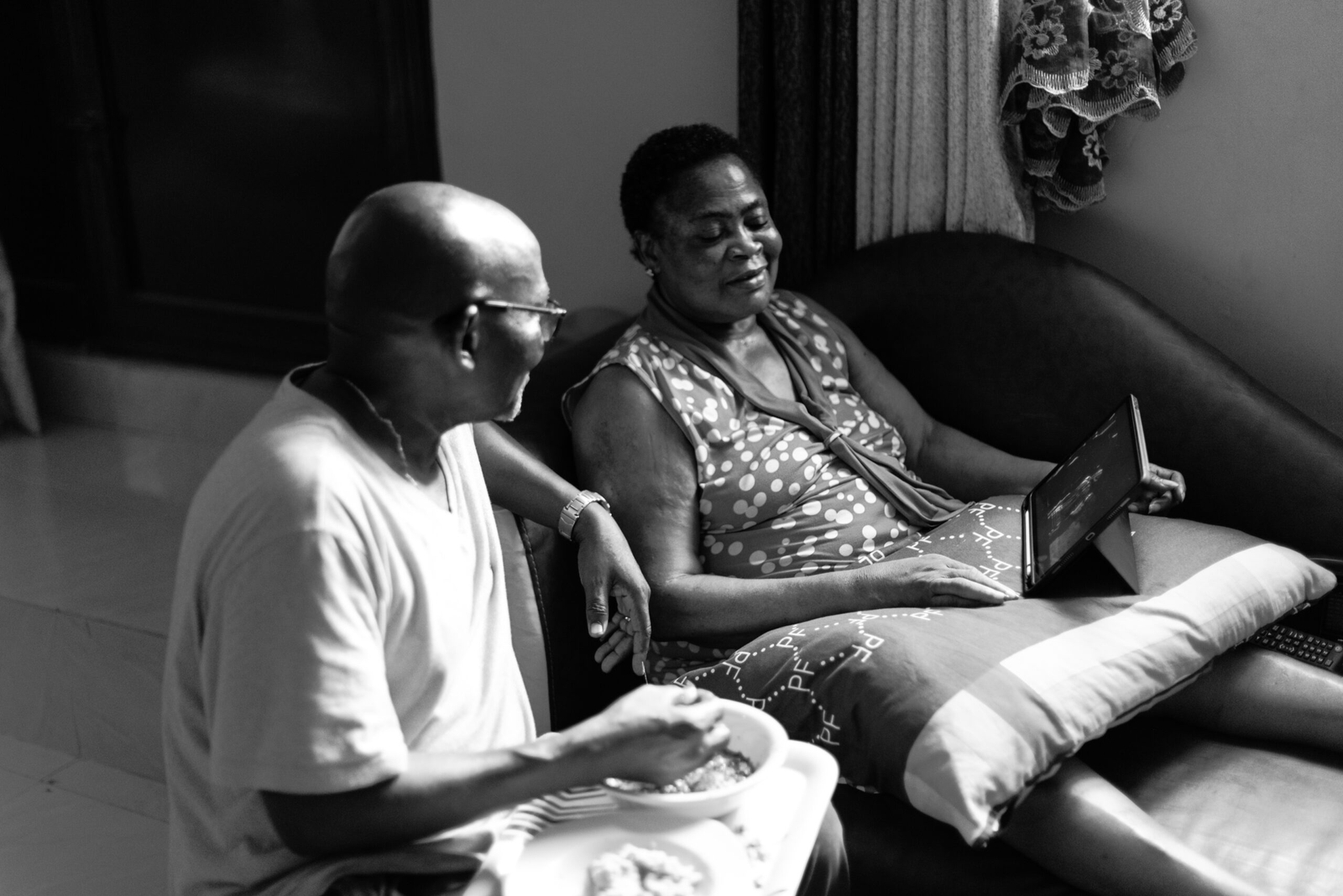

When BOC fell sick some years ago, Ronke was by his side for the entire time it took him to heal. In addition to her already established role as a ‘wife’, Ronke had to become the primary decision maker in the home, a role we had always conceptualised to belong to BOC because of the power associated with him as the ‘man’. She did these while pursuing her career and role in government. She seemed to be doing it all.

This was perhaps the first sign of how we can defer power. Except in this case, we do not believe BOC did this voluntarily; he was sick.

As children, we did not necessarily see this as an expression of love, intimacy, care and affection within complex power dynamics. We did not see this as an expression of agency, a choice Ronke made, and a form of suffering that comes from love.

As adults, we asked her why she did it, and she could not give a reason. She said, “I just did it for him.” And that was it; she did not think it was something she needed to rationalise.

Unfortunately, we exist within a culture of dominance formed through patriarchy, which often frames relationships as a constant power struggle. However, when we reduce our relationships to the inequalities fostered by systems of power, we ignore how it exists simultaneously with agency, intimacy, and tenderness, despite the inequalities. There are complex forms of love that can transcend inequalities.

Ronke showed some of this when we probed further: “When I did it then, I did it willingly. If my husband dies, who will help me take care of my children?” While the expectations placed on her might have played a part in her decision to do what she did, it sat within a simultaneous form of agency formed from love for herself, her husband and her children.

[Photography by Adebayo Quadry-Adekanbi]

[Photography by Adebayo Quadry-Adekanbi]

Olúranlọwọ lẹ je (you are helpers to each other): Reciprocity in Love

As we have grown older – some of us are married, some of us with children – we have grown to understand the complexity of love; the complexity that shifts love beyond a feeling, but an act that we must choose to commit to every day, particularly when confronted with complex dynamics of power as a result of our gender or sexual orientation.

Various incidents have tested our love as a family, and one recently came up when Ronke had a stroke in April 2022. Ronke is what we describe as a strong woman, so we never previously got to experience BOC repaying the favour of her staying by his sick bedside all those years ago.

While Ronke has a stay-at-home nurse and help, BOC has been active in her care, cooking for her, serving her food, cleaning up after her and bathing her. He has also taken the responsibility of going to the market to buy groceries.

Ronke made it a habit to do these things by herself, and he wanted her to feel like, with him there, she still had some control. He knows what she would want, he can easily identify her regular vendors – or they recognise him, and she can trust that he is getting the best after years of negotiating what they both like. Watching him haggle with people at the market and navigate the space buying rice, beans, peppers and so on has been amusing. What were previously miraculous exceptions have become the norm.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

This might seem like doing the bare minimum for someone you claim to love, and some would say it is. But it has been a revelation seeing that love in action because many of the activities BOC is performing are those that we believe are antithetical to his belief system of what he should be doing as a “man.”

However, when confronted with the question of why he is doing all this, BOC said: “When there is a storm in the family, you need to find out how to stop it. What I am doing now, I am happily doing it. Because I need to do it, I must do it.”

He proceeded to sing a part of an Ebenezer Obey song, ‘Eto Igbeyawo’, that roughly talks about how a couple should help each other in the name of love:

To’kọ Ta’yà ẹ máa jáa (husband and wife, do not fight)

Ta’yà to’kọ ẹ máa jáa (wife and husband, do not fight)

Nítorí Olúranlọwọ, Olúranlọwọ (because you are helpers to each other)

Olúranlọwọ lẹ je (you are helpers to each other)

Ẹ fárá yin mọ́ra o (pull each other close)

Olúranlọwọ lẹ je (you are helpers to each other)

He continued, “So, I must be a good husband to my wife. Because she has done it for me so many years ago, and I know she would do it again if, God forbid, it happens again.”

Ronke created a loving man

This was when we saw how Ronke’s actions those years ago were acts of love, and how they showed BOC his capacity to love. By loving BOC, Ronke showed him he could also love her, and she showed him how to let down his ideas of masculinity to show love to her when and how she needed him to.

We see this love in the gentler moments where he encourages her not to feel bad for her illness, holds her hands, prays for her, stands to watch her eat to make sure she has everything she needs, or dances to her favourite songs and tries to make her laugh.

At a time when ableism is rampant, particularly towards Black women and their healthcare, we got to experience BOC dealing with Ronke with care, patience and understanding.

Ronke made a similar statement: “what I did then [when BOC was sick] is what I am enjoying now. He saw that, ‘a wife that has done this for me, I need to do it back.’ And I am happy because he is doing it.”

To us, it seemed an act of love expressed by Ronke created the loving man that could love her. A man that can express his feelings more and be more open to receiving love.

In the middle of our conversation with Ronke, BOC called her to check in on her, and all we could see was a big smile on her face. We asked why she was smiling when she got off the phone, and she said, “he said he liked how my voice sounded on the phone.”

How we defer power voluntarily sometimes because we love

So, can love fix our complex dynamics of power? If we chose love, could we overcome complex dynamics of gender and sex, sexual orientation and class, especially on an individual level – in our homes, office spaces, etc.? Does an illness have to happen for us to choose to love in ways that crumble power dynamics?

We think this dynamic is a more accurate expression of how we can often voluntarily defer power because we love. After all, this incident does not exist in a vacuum and does not remove BOC from a society of complex gender dynamics where his gender allows easier access to power.

Therefore, he is not letting go of his power completely; he is simply deferring it.

The constant tension between the aspiration and the execution

The discussions here can be seen as largely aspirational, and that is in constant tension with the execution. Is it genuinely possible for men to become loving members of society?

Growth is not linear, and BOC’s growth has not been linear. His expressions of masculinity have not entirely changed from his previous understandings of it, and we see signs of that sometimes.

However, if at times men behave in line with our aspirations and other times they relapse to primitive socialisations, that doesn’t make the project of creating loving men a complete failure. It is simply realistic to the moment we live in.

Unfortunately, we can often never fully arrive at the aspirational place because primitive socialisations are deeply ingrained.

We have presented evidence of what is possible and want to keep aspiring to that. After all, what do we achieve if all we can say is that “all men are shit?”

Because the truth is yes, they can be shit, but it’s possible for them not to be, and we have to start looking at the ways that can happen.

Ronke is recovering amazingly, and BOC is right there by her side. We are grateful for their love and cannot wait to see other beautiful things that can come out of a dark moment.

Written by: Adebisi Akinwunmi, Adebola Farinmade, Adebanke Bolade and Adebayo Quadry-Adekanbi

What can you do?

- Read All About Love by bell hooks

- Read The Will to Change by bell hooks

- Read Introducing Love: Gender, Sexuality and Power by Deevia Bhana

- Listen to a playlist of some classic Yoruba (mostly) love songs curated by BOC and Ronke

- Read more articles by Adebayo HERE

[Photography by Adebayo Quadry-Adekanbi]

[Photography by Adebayo Quadry-Adekanbi]

[Photography by Adebayo Quadry-Adekanbi]