In 2017, I started a campaign to make upskirting a sexual offence after a group of men took photos of my crotch at a festival without my consent.

I did everything we ask victims of sexual harassment or sexual violence to do – I got the evidence by grabbing one of their phones with the picture on and handed it in; I had witnesses; I reported it instantly to both security and the police – yet I was still let down and told I wouldn’t “hear much from them”.

This didn’t shock me.

It’s important to caveat here that many women and marginalised people don’t feel they can turn to the police in cases of sexual harassment, especially in light of the attention drawn to police violence after the recent murders of Sarah Everard, Sabina Nessa and a long list of others.

Yet even though I did go straight to the police that day in 2017, I shouldn’t have expected much more than I got. Back in 2014, I had a two year case out against a man from school who was cyberstalking me. I learnt, during that experience, that the police had, quite honestly, zero clue what to do about the harassment I was receiving. Only now, the week I am writing this, has he been sentenced to jail.

When I reported the upskirting incident, I was again met with derision and ineffective action. So, when I headed home from that festival, I decided to take matters into my own hands.

I started by uploading photos to Facebook. They were selfies of me and my sister, with one of the perpetrators in the background, and I asked my followers to share and identify the man. However, Facebook quickly censored me, citing that I was ‘harassing’ him. How ironic.

Once again, my experience of harassment had been dismissed and I was left exposed to the realities of institutional sexism. I remember thinking at the time that I couldn’t change the system as a whole, but that perhaps I could change a part of it. So, I decided to try and add upskirting to the Sexual Offences Act 2003.

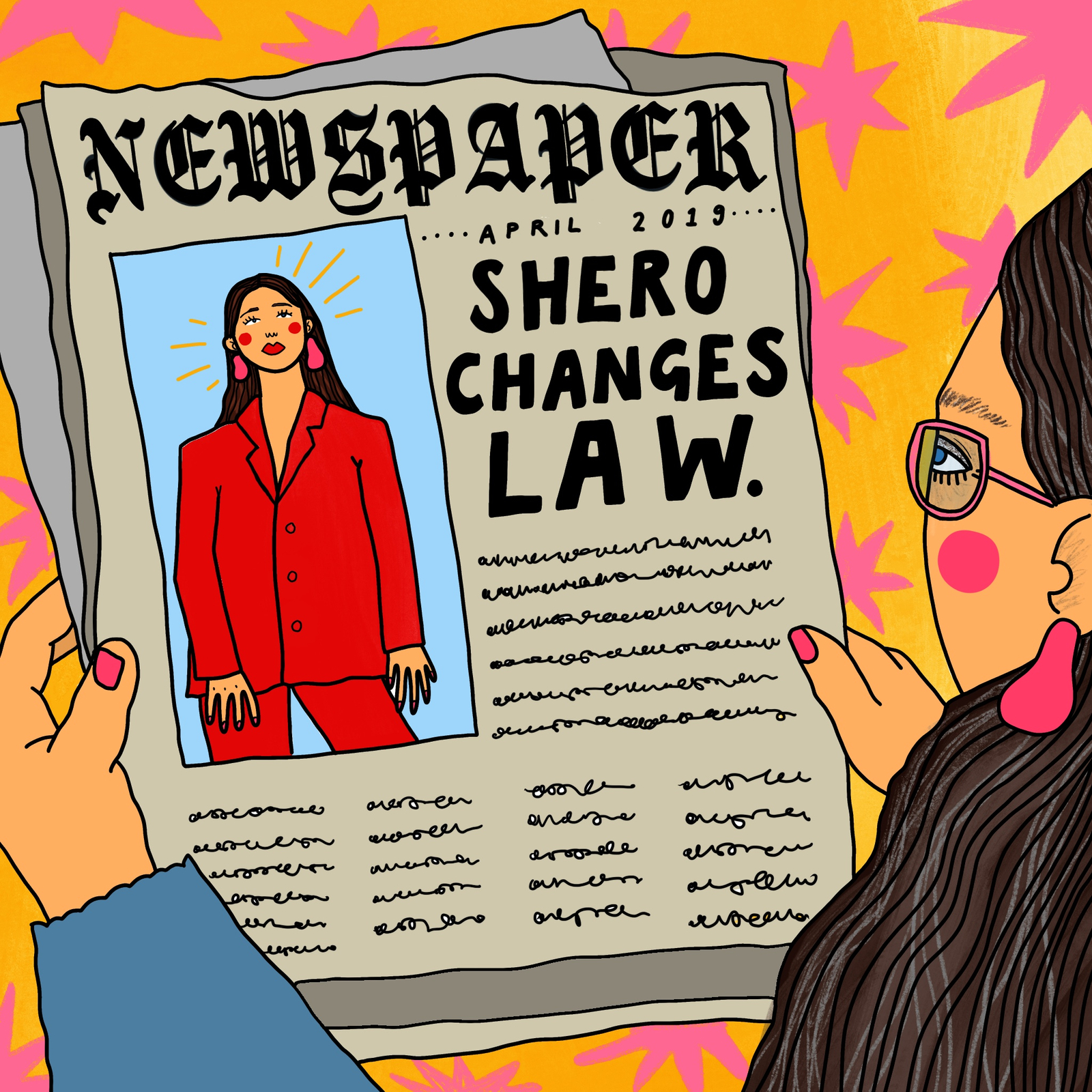

I spent two years campaigning and working with parliament and my lawyer to change the law. In 2019, we won our case and upskirting was made a sexual offence. The first two men to be prosecuted were convicted paedophiles, one with 250,000 photos of children on his devices. It’s been a recurring theme in upskirting prosecutions, which often catch repeat and violent offenders.

While this was an undeniable success – who doesn’t want to root out and put an end to men preying on women and children? – the subsequent media attention began to turn me into the poster girl for carceral feminism.

Carceral feminism is a critical term for a type of feminism that frames criminalisation as the answer to sexual and gendered violence. It often cites solutions like ‘harsher and longer sentences’ for perpetrators, and rarely delves into prevention.

It is particularly prevalent within white feminism, which can be recognised by its exclusionary focus on the struggles of white middle class women. This elitist and racially prejudiced ‘feminism’ largely excludes and dismisses the realities and struggles of other women, and betrays the intersectional principles which founded the movement.

Koa Beck says that “white feminism is enduring because it’s so palatable.” It goes hand-in-hand with this carceral feminist mindset – upskirting is bad, paedophilia is abhorrent, so criminalisation is the simple solution. But what about the Black women, the trans women and the sex workers, whose bodies are already policed and have a well-founded distrust of the police and prison system?

Indeed, carceral feminism is so often an iteration of white feminism due to the fact that it overlooks the harm the prison system perpetrates against people of colour and other marginalised identities. It looks for solutions within existing police structures, because these structures have historically worked in favour of (and were created by) white people.

I didn’t know the term ‘carceral feminism’ when I was just journeying into intersectional feminism at age 25. I also didn’t know about the perception of me and my work. I’d been campaigning behind the scenes every day for a year without any significant platform. I was learning as I went; I was hurt and angry and didn’t do a lot of reflecting.

The momentum was outrageous. I spent every day planning, reacting and putting out fires. But when I started getting on the news, being plastered over papers and being dubbed as a ‘changemaker’, ‘girl boss’ or ‘shero’, I began to feel deeply uncomfortable.

In 2019, I suddenly saw what I was being portrayed as; I was being held up as an aspirational white feminist figure in a red suit.

Comments in interviews where I would disclose how much I’d taken on were tweaked to remove the mention of how hard I was finding it all. Instead I was offered up as a shiny example of how you can “have it all”. I wore a beret and a journalist wrote about my outfit as if I was trying to dress like a revolutionary. It was so contrived.

A year into the law change, a peer of mine pulled me up on how my work, and some of the things I’d said during the campaigning (which I’d kept moderate to keep the Government on side) had buoyed up carceral feminism. So I started to ask myself: “was I the poster girl for it?”

The answer was short: yes.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

When I was fighting to change the law, did I believe criminalising people was the solution to the problem? Absolutely not. Prevention is always better than cure. That’s why I talked about upskirting as part of a continuum of violence and discussed how we get to this place and how to prevent it as much as I did the law. But that didn’t matter. I was literally working for criminalisation.

When I started this campaign, I didn’t think a system could be changed. I thought the only way to create change was by working within it and so criminalisation felt like the biggest and only possible solution.

But as I continued to work in the activist space, met people, read more, educated myself about abolition, I began to understand how the successes we have achieved throughout history have been led by people with enough imagination to fight for a different society, not just a slightly different system.

I also started to realise that criminalisation didn’t prevent anything. I wanted to erase the campaign and undo the harm I might have caused by making hundreds of white feminists believe criminalisation is all there is. I wanted to move away from it completely and spend the rest of my career working towards prevention, education and facilitation.

However, to hide my journey and not sit with my privilege and the harm it may have caused is also wrong. Feminism is a living and breathing movement; I needed to grow with it.

I remembered a tweet by Kelechi Okafor, “I want prisons to not exist *but* I also want Derek Chauvin to serve 15 million years. I will unpack this in due course.” I felt similar about the men who had hurt the women and children that my law had caught; criminalisation doesn’t solve this problem. It never has.

The police solve just 7.8% of all recorded offences and prisons don’t rehabilitate people. But, I also don’t want those men on the streets. So, here’s my answer (for now). I’ll no longer promote criminalisation as the answer to sexual violence.

One day, the poster of me in the red suit changing the law will be tattered and peeling, and the woman staring at the poster will be me. I’ll be 50 years old (still hopefully wearing red) working with people to prevent this harm outside of existing harmful and racist structures, not with the system to criminalise it.

In this image, the artist has attempted to playfully illustrate the complex nature of the relationship between Gina Martin and her younger self – a self that was touted as a hero of carceral feminism, as well as her older self, a self who is more focused on societal upheaval and system abolition. The line “the poster of me in the red suit changing the law will be tattered and peeling, and the woman staring at the poster will be me, 50 years old (and hopefully still wearing red)” is the imagery that sparked the idea for this piece, and inspired the artist to create this particular illustration for the article. Bee’s artwork hints at an older, more reflective and pensive Gina, looking wistfully back at newspaper headlines from the time when she was campaigning for upskirting to be made illegal.