Mei Yuk Wong is a UK-based artist, whose installation Fragments opens this Thursday in Manchester. Fragments operates at the intersection of arts and academia, and sees a collaboration between Mei Yuk and scholars working at the University of Manchester on their Reckoning With Refugeedom project, to create an installation commenting on the global experience of displaced communities in modern history.

The topic began to resonate with Mei Yuk on a personal level following the wave of protests in Hong Kong. “I was born in Hong Kong. My father was a refugee who escaped from China to Hong Kong when he was fourteen. Though I have lived in the UK for over twenty years, the current situation in Hong Kong urged me to do something; making art was a way of showing my concern.”

shado sat down with Mei Yuk and lead researcher Professor Peter Gatrell to find out more about the installation and the parallels that can be drawn from the archival material, which documents historical materials from 1919-1975, and current experiences faced by refugees today. Mei Yuk’s personal attachment to Hong Kong aligns the artist with other forcibly displaced communities. ‘Refugeedom’ is circumstantial; “it could happen to anyone”, she says. It is precisely these parallels, and “the relevance between the past and the present” Mei Yuk explains, which makes the installation so important – and one not to miss.

History follows a pattern which has left stories from refugee communities excluded from the mainstream narrative.

This lack of self-representation has created a culture of victimisation and homogenisation where the individual voices have been excluded or hidden amongst the numbers we are shown in the news. This is true not only for the communities reflected in Mei Yuk’s work but also for groups today who are facing displacement.

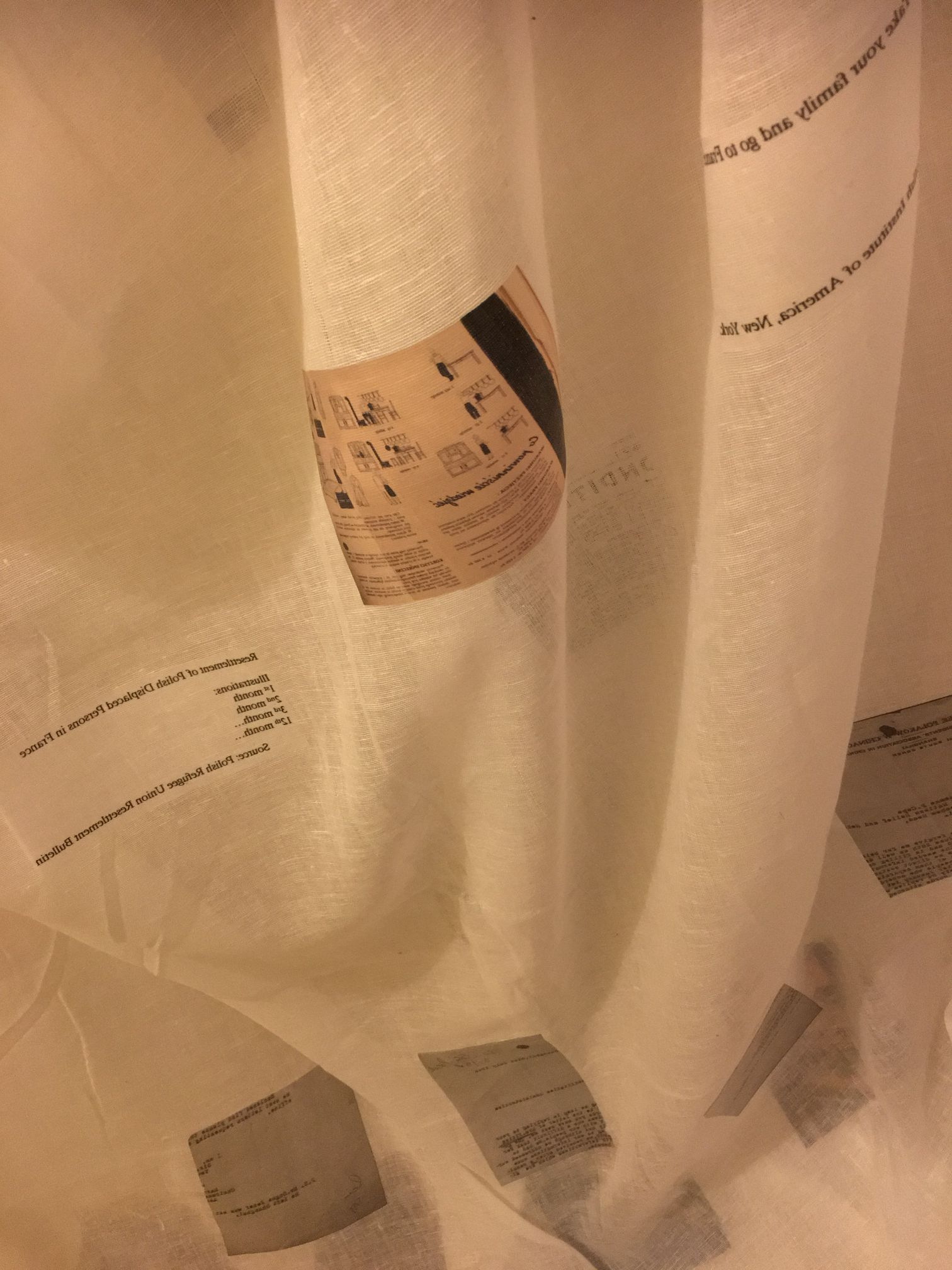

By including archival materials from a range of communities over the period of 1919-1975, including Russian and Armenian refugees in inter-war Europe, Eastern European Displaced Persons after 1945, and refugees in South Asia in the aftermath of the Partition of India in 1947, the installation exposes these stories as being part of a shared and global history. This is important in recognising that these experiences are not confined to specific periods of time in history or certain communities but have been experienced and are still being experienced by communities all over the world. It is this shared experience of movement, displacement and persecution which weaves together the fabric (literally and metaphorically) between these narratives and encourages the viewer to look not only at stories from the past but to recognise and reflect on the realities that are being faced today for groups globally.

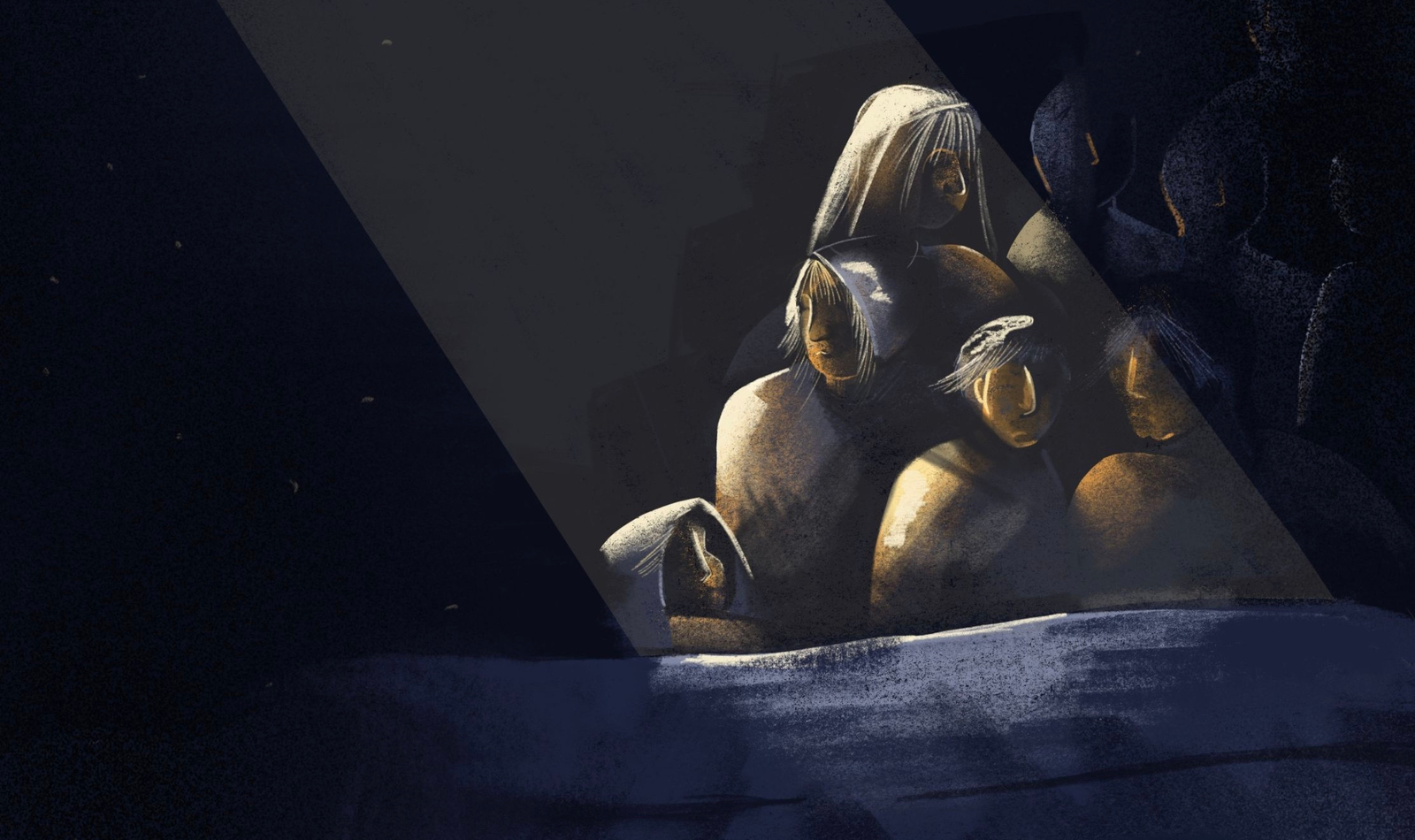

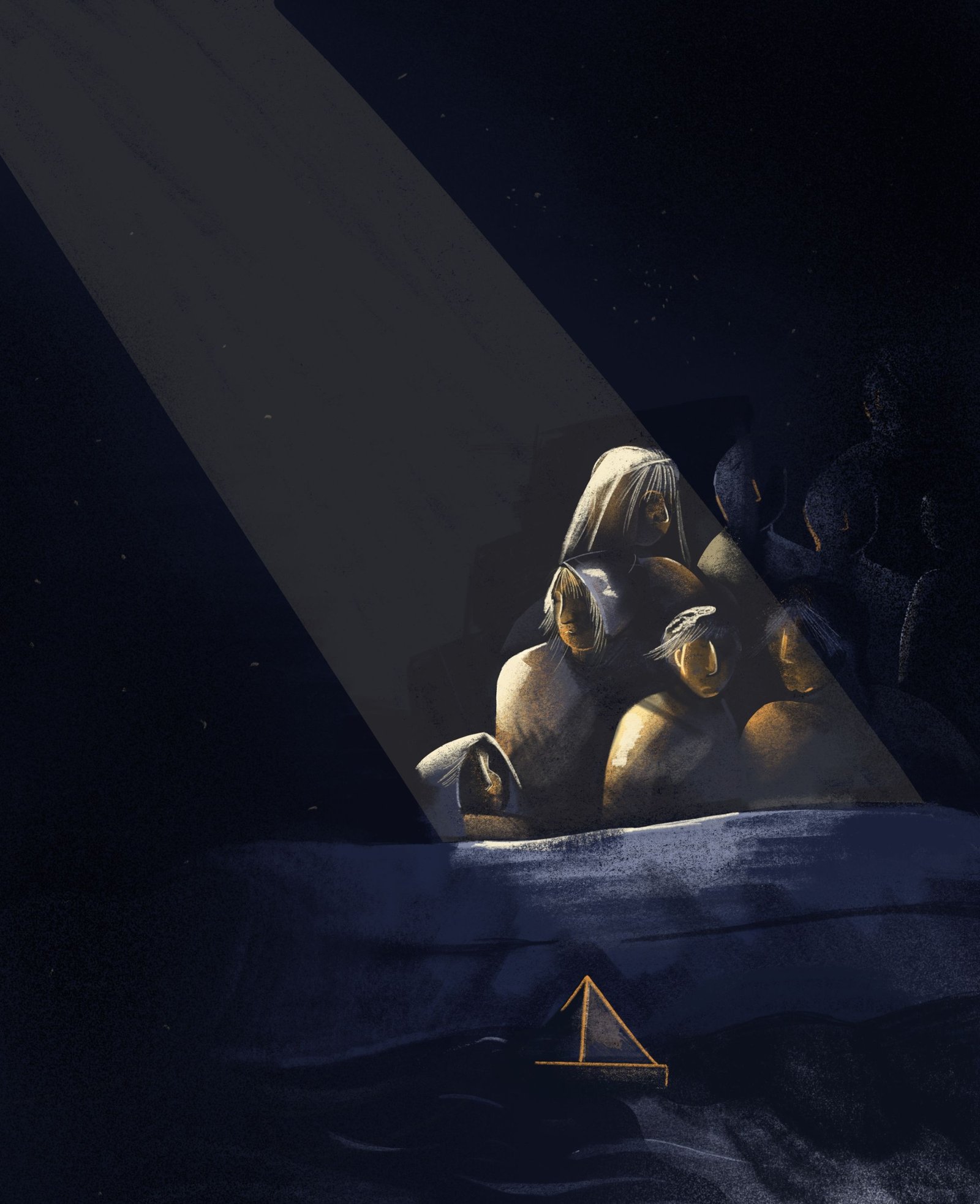

“History has made refugees voiceless,” says Professor Gatrell, whose own work with the files of UNHCR in Geneva aims to insert displaced people back into the historical narrative, and to move away from “lumping [refugees] together as a single mass of suffering humanity.” However, what is clear is that we will never know the full story – we are only afforded whispers of personal stories, through a personal letter or a polaroid picture, which we can stitch together to try and learn about a shared experience of displacement. This is what Mei Yuk’s installation physically embodies.

There is a large storytelling element to Fragments which involves the weaving together of letters, pictures and petitions created by individuals in the times and places mentioned above. By sewing the work into muslin – a thin, almost transparent cloth – Mei Yuk encourages the viewer to see the installation as a window into these individual experiences. As she explains, “We don’t know the whole stories or the whole picture”. The fragility of the muslin creates this atmosphere; incomplete and ethereal. Looking back today, we can never fully understand the stories lost to history – all we get is fragments. But fragments themselves can tell us a great deal.

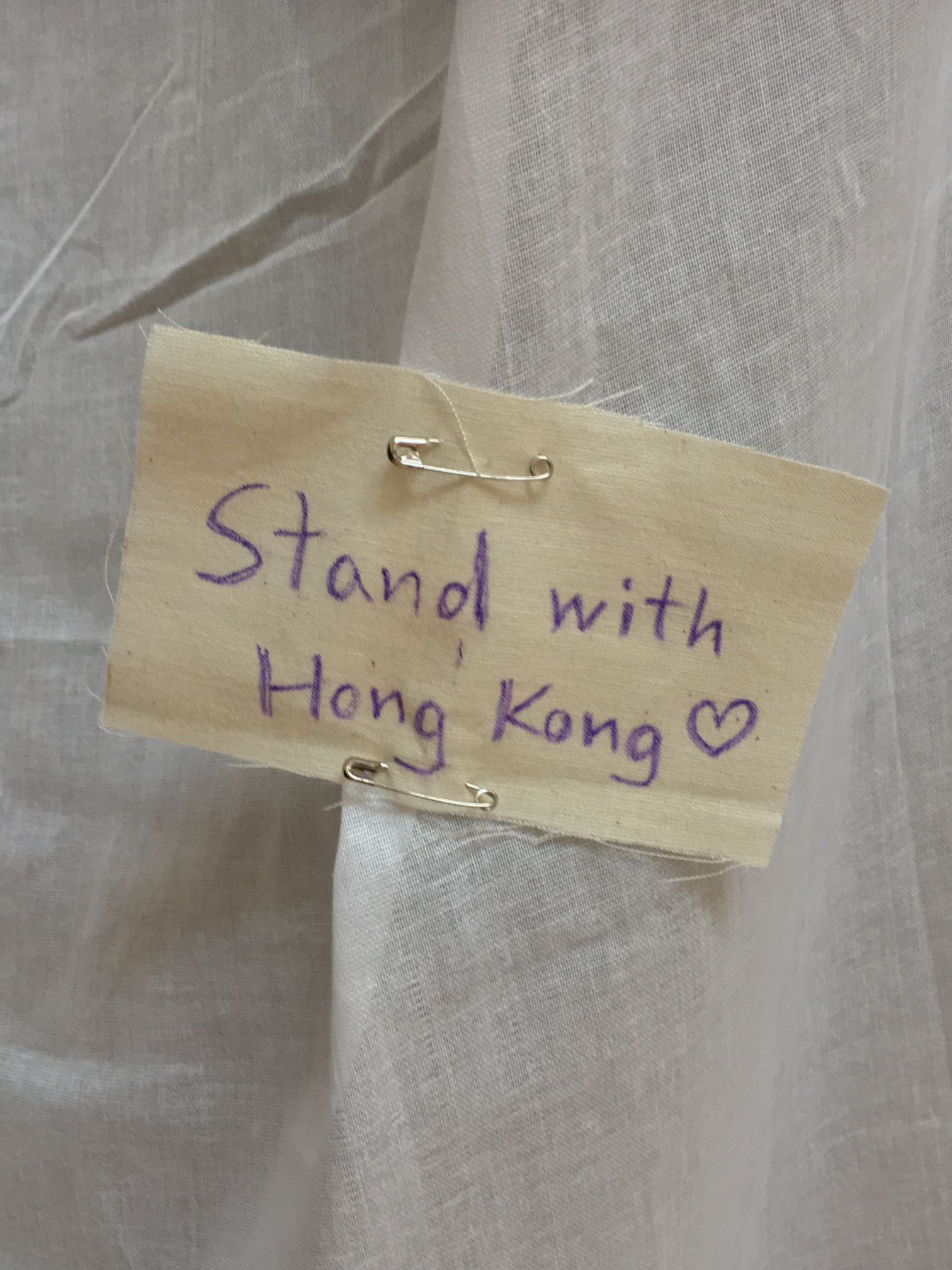

Because the voices of displaced communities have been historically silenced, little has been shared of the agency of these groups, and the important resistance and protests that were made in relation to human rights, justice and accountability voiced at the time. What is exciting about the archival material used in Mei Yuk’s installation is that they document just that: different petitions, calls-to-action, and modes of defiant self-expression adopted by displaced people around the world, throughout time. These snatched narratives are patched together, but still leave gaps – which is where audience participation comes in. Visitors are encouraged to write their own thoughts and messages on fabric pieces and pinning them to the hanging work: this is its own miniature form of resistance; a show of solidarity, which inserts the viewer’s voice into the installation alongside the accounts of refugees throughout history. Ultimately, the gaps in the facts found in the archives can only be filled in the minds and imaginations of those encountering them.

The installation is Mei Yuk’s effort to offer a new way of storytelling and to give a new life to the documents, which make up parts of human stories that have been stored away in archives. “Apart from the researchers,” Mei Yuk says, “who else is going to see the archives and know the stories of refugees? I felt like I needed to reveal the hidden material and ghostly stories. Otherwise, they will only be stored in boxes forever.”

This transfer of knowledge from academic to artist provides an important collaboration – and one we hope to see more of – not only in working to insert narratives back into history but in providing accessible platforms for these stories to be shared.

The installation opens on Thursday 26th September at PS Mirabel 14/20 Mirabel Street, M3 1PJ, as part of Journeys Festival International in Manchester and will run to 19th October. For further details please visit: www.journeysfestival.com.

Scholars include:

Dr Alex Dowdall, Research Associate, University of Manchester

Dr Kasia Nowak, Research Associate, University of Manchester

Prof Anindita Ghoshal, Associate Professor, History Department, Diamond Harbour Women’s University, Kolkata

Prof Peter Gatrell, History Department, University of Manchester

Written by Hannah Robathan and Isabella Pearce