Flags are, by their very nature, a political manifestation of allegiance. They have the ability to elicit wildly different emotions depending on the beholder: a St George’s Cross is always guaranteed to mobilise me into alertness, while the Saltire gives me a little glow of burning pride.

I know there are many older people in the Vietnamese diaspora who don’t – or won’t – recognise the yellow star on a red background. One of my favourite games to play when I visit the US is ‘count the flag’, because the sheer presence and power of the American flag as a tool of national identity never fails to amaze me.

Needless to say, I am sensitive to flags, so it stands to reason that one failsafe way to get me to support an independent business is to hang the flag of a marginalised community in the doorway. My favourite independent bookshop and local bike shop, for example, are both draped in the Progress Pride flag, a welcoming beacon that says, Hey, we have the same values. Come shop with us.

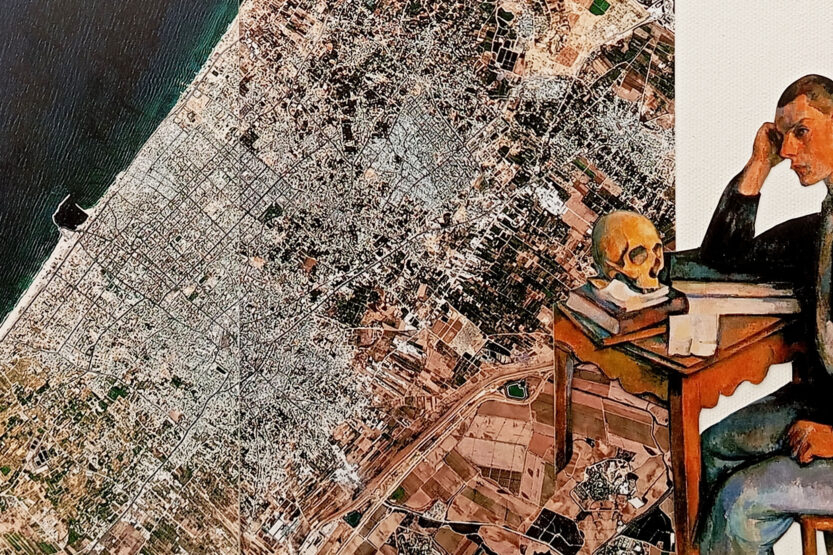

Similarly, my local West Asian supermarket is actively engaged in the Palestinian struggle; they sell Palestinian flag lanyards to raise money for relief efforts in Gaza, and there are several posters tacked to the front door to educate on and encourage participation in the BDS movement.

Like many of its kind, it’s an immigrant business, and while it stocks predominantly regional produce to serve particular community needs – notably, produce of Palestine, Lebanon and Syria – it also has the standard offering of most convenience stores, or ‘corner shops’, as we tend to call them in the UK, as well as homemade savoury pastries that absolutely slap, and some excellent loose fruit and veg, which speak favourably to my eco-but-budget-friendly values.

And yet, while the products on offer are certainly appreciated by community outsiders like myself, the stock strikes me as just one thread of a very complex woven tapestry: contained within that one, small space is a whole history of a country left behind and a new community found.

Such is the case with the gloriously detailed set for Ins Choi’s Kim’s Convenience, a play-turned-sitcom about a Korean-owned convenience store in downtown Toronto, first brought to life in 2011, but which premiered in the UK for the first time in mid January this year at the appropriately named Park Theatre in London.

Contained on set within a theatre that seats 200 people was a personal museum of history and migration, complete with Lays crisps imported all the way from Canada. Subtle touches like the modest wooden crucifix, family photos, Chuseok poster and – of course – a South Korean flag, told the audience so much that wasn’t said in the lines spoken on stage.

Paying it forward

Some may not believe that daily shopping is a political act, but subtle references in Kim’s Convenience remind us that it most certainly is. At one point, while discussing the news of a Walmart coming to the local area, the play’s lead, Appa (Korean for ‘dad’), speaks the words:

“This community needs me. Even if Walmart is moving in, people still need this store.”

A small, independent store staring down the jaws of the big, corporate beast is a common theme of resistance among small businesses caught in the waves of gentrification that have swept Western nations in the last few decades.

Still, however, the mighty British corner shop clings on, ‘like a cat with nine lives’, although the current cost of living crisis and surge in energy prices may prove to be its greatest test yet. Supporting small, local businesses during times of economic crisis has become normal for many socially-minded people – and increasingly, that support has extended to times of social crisis, as we’ve seen in past years with the rise of Black Pound Day in response to the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, the drive to support ESEA (East and Southeast Asian) businesses during COVID-19 lockdowns (and subsequent rising anti-ESEA racism), and now with the genocide in Gaza.

A common theme has emerged through all these crises: the mission of white supremacy, peppered with colonialist legacy. And yet, Kim’s Convenience reminds us again of the importance of cross-community solidarity in the face of such common struggles, with Appa relaying an anecdote from a fellow Korean supermarket owner, well established in a Black community in Los Angeles, who found their store protected from looters by it Black customers during the LA riots in 1992.

Given the true historical context of the riots, also known as the King Riots (following the killing of Rodney King by LA police) or sa-i-gu (to Korean Americans), in which 63 people were killed and which caused deep fissures between Black and Korean communities, it feels like Choi is issuing an important reminder: the times of greatest conflict are those in which we need each other the most.

The supermarket as a space of cultural importance

Like many others, I believe that if I am obliged to exist in a capitalist society that over-values commodity and productivity, I might as well spend my money in ways that align most with my values.

Last year, I moved back to the UK after eight years in Senegal. For nearly a decade, my local buutik (Senegal equivalent of a corner shop) was my go-to for all my everyday purchases; it’s also where you are socially obligated to do the “salaam aleikum”, the “nanga def?” or the “waali jam” before requesting your purchase. Finding that the closest shop to my Edinburgh flat is a Sainsbury’s Local, where I can complete my entire shopping experience in total silence at a self checkout machine, was something of a reverse culture shock.

Of course, I must acknowledge that living in a city makes it easier to access various different independent supermarkets without travelling too far – many people are forced to rely on big chains like Asda or Tesco for their shopping. But when we are able to access independents and spend our money mindfully, we discover so much more than the products we come away with; we are privy to other, more important community transactions, and we support people we can actually get to know, rather than nameless, faceless CEOs with more money than they know what to do with.

However, try as I might, it became all too easy to nip to Sainsbury’s for things I could definitely get at smaller locals if I could be bothered to walk further than 70 metres. And so my New Year’s resolution for 2024, among many others, was to support predominantly local businesses, and rely on big chains for the occasional thing, rather than the other way round.

Newly convinced that solidarity with immigrant supermarkets would save us all, I spoke to a few politically engaged people in my social and activist circles about their shopping habits, including Vicky Bellman, therapist and perpetual chef, who shares: “As a white person who cooks predominantly ESEA food, it’s where I source my ingredients that helps me figure out the line between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation. It doesn’t bypass the communities that I’m borrowing from; it’s a give-and-take transaction that doesn’t feel one way.”

She adds: “Even if I’m not sure of the social or political values of the stores I shop in, me shopping in them is a political act.”

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

Local convenience stores are also important community focal points for conversation and knowledge exchange – Vicky is always asked by her local Chinese supermarket owners what she’s cooking that day – and they provide grounding spaces of comfort for people in diaspora.

Alix Homfrey, a case worker for an ESEA hate crime reporting service, project coordinator for ESA Scotland and member of the group ESEA Outdoors, grew up just outside Glasgow. She speaks fondly of a Chinese supermarket that’s been part of her life for as long as she can remember. “I would often pass by Mr Lim’s for some snacks after Saturday Chinese school when I was a kid, and when I was in uni I lived nearby so I could pick up wee bits to cook in my flat, and share some of my heritage and my mum’s cooking with my flatmate,” she shares. “It’s a small and packed wee place and it was a comfort while at uni and therefore less often fed by my mum’s Cantonese style cooking.”

At this, I thought of Appa’s insistence that Kim’s convenience store was needed by his community, even in the shadow of a superstore. Alix’s next words confirmed my thoughts. “There’s just comfort in its constant-ness,” she says. “I’ve visited on and off for so many years and have memories tied to it. So a selfish part of me wants to support and help keep them going to keep my own memories and comforted feeling of always seeing it there. Seeing it stick around for so long feels like a reflection on our ESEA community also being able to stick around and really settle into place and home here, too.”

Local businesses have a huge role to play in supporting individuals in their communities. For example, Edinburgh’s Typewronger bookshop and this Twickenham corner shop both host customers on Christmas day – offering everything from soup, tea and hugs – to combat loneliness. These acts of – and for – community make the independent business so much more than a place that provides goods and services. They provide the meaningful connection, not just with the business, but with community and, indeed, with yourself, that I was missing when I left West Africa.

Aileen Lees, a community organiser also working with ESA Scotland and ESEA Outdoors, told me about the importance of her local ESEA supermarket when working in Milton Keynes. “The unique part about the supermarket was that it has a restaurant inside. The no-frills Mii & U was like a canteen, serving delicious dishes at reasonable prices. This was such a haven for me, living and working in an area with a dearth of ESEA-owned restaurants that also catered to ESEA people,” she shares. “It would transport me out of Southeast England and back to Southeast Asia. Everything about the place was nostalgic. It brought back childhood memories of making the ‘big trip’ to the city just to get supplies from the Chinese supermarket. But it’s also the feeling of having to travel to a dedicated place in order to access your culture, to feel like the majority. It’s why Asian supermarkets today still give me a sense of home and belonging.” This last point resonated strongly with me. Living abroad at the dawn of my ESEA community activism, it was easy to feel isolated, so Asian supermarkets, which provided the ingredients I needed to bring community joy to the kitchen, gave me something to grasp onto.

A space of cultural mediation?

Kim’s Convenience is a dedication to immigrant businesses exactly like the above. It’s also a story that shines a light on the challenge of raising children in a different country to the one you’ve left behind. We see, through the interactions between fiery daughter, Janet, and estranged son, Jung, the weight of parental expectation and sacrifice grinding against the overwhelming desire to fit into Canadian society.

The play also reminds us that many tensions between diasporic communities are alive and well. Although hilarious on stage, grudges such as Mr Kim’s suspicion of Japanese manufactured cars mask deep historical friction between Koreans and Japanese, following the 35 year occupation of the former by the latter.

We might draw parallels to the gastro-diplomatic disagreements between Algerians and Moroccans over couscous, or Ghanaians and Nigerians over the origins of jollof (although I’ll draw my own line in the sand there and insist that jollof was invented in Senegal). An amusing feud on the surface, but the scars of social and political conflict between these respective countries of origin run deep.

I asked myself: how does that friction manifest itself when these communities are “away from home”, when they are transplanted into a new, third country, one which is more likely to see them as a monolith, of Asians, Arabs, or Africans? Does the immigrant-owned supermarket serve as a place of informal cultural diplomacy?

Perhaps it is an investigation for another day – and one that might see me well fed and sent home with more than just a few ingredients. For now, we cannot escape the fact that, today more than ever, it is important not only to support independent, immigrant businesses, but to champion and celebrate them.

Saddened to hear of the closure of Stratford’s Market Village, home to many small and immigrant-owned businesses, in 2024, I demand to see more exhibitions like the Migration Museum’s 2023 “Taking Care of Business”, an immersive space that paid homage to the immigrant entrepreneurs who shaped modern Britain.

As we show up for global social justice with our bodies, our words and our wallets, in a world that grows increasingly dark, may we take the lessons of community care, learned from our local independents, and apply them throughout our daily lives. As the great Angela Davis wrote in Freedom is a Constant Struggle, “it is in collectivities that we find reservoirs of hope and optimism.”

Kim’s Convenience is on at the Park Theatre, London, until 10th February 2024

What can you do?

- Support businesses run by people of colour or other marginalised groups. Consult directories such as Black2Business or British Chinese Biz.

- Actively seek out independent business and brands through online research, social media and word of mouth. If we don’t seek out small businesses, they will cease to exist. Small businesses often have the added benefit of being less implicated in systems that may conflict with your values, such as environmental or political.

- Buy gift cards! Gift cards are a great way of introducing your friends – potential new customers – to a business you love.

- Join local community initiatives and collective action to protect businesses at risk of closure, whether via fundraising, protest or writing to your MP.

- Articles to read: