In Recife, a city in the north-east of Brazil, a group of people experiencing homelessness gather in a square. As they dance, listen to music and laugh, they also confront the viewer, making their demands: for respect, food, work and housing; for an end to the epidemic of murders in transgender communities, and for the ousting of neo-fascist president Bolsonaro.

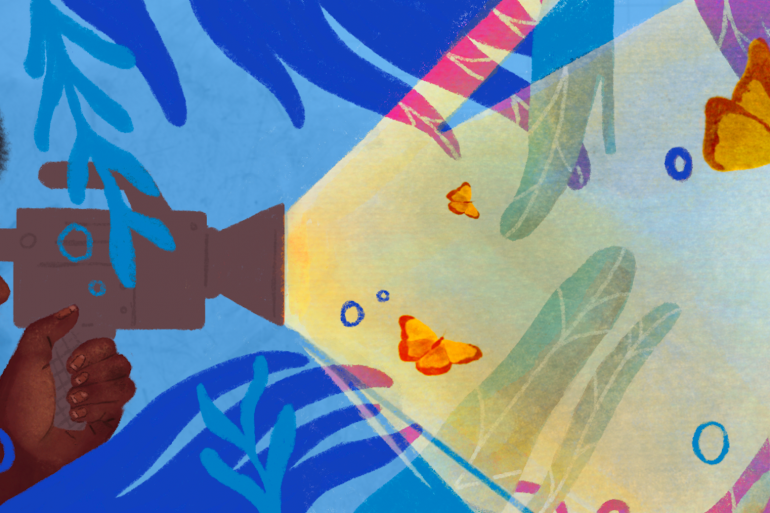

This is the opening of Out Loud, a new film by Jonathas de Andrade, a visual artist, born in Maceió, in the Northeast of Brazil. In his work, he uses installations, photographs, film and other media to discuss social issues in Brazilian popular culture and addresses questions of identity, class, race and sexuality.

The film, starring a cast of over 100, aims to reposition the stories of houseless communities. It examines the colonial gaze and the power dynamics that form life in modern Brazil, and asks the audience to consider new forms of understanding towards those experiencing homelessness.

I spoke to Jonathas via video call late last year from his apartment in Recife, an area which encapsulates the current housing and wealth inequality in Brazil. I was especially excited for the call as, since 2018, I have been studying the relationships between class, race and identity in contemporary Brazilian cinema.

Talking with Jonathas was an important exchange, especially now that I am in the final phase of my doctoral research on racial representations in the films of Kleber Mendonça Filho – a director also from the northeast of Brazil – at the Graduate Program in Cinema at the Universidade Federal Fluminense, in Rio de Janeiro.

The rising levels of homelessness in Brazil

Brazil contains conflicting realities. An abundance of food has transformed Brazil into a leader in food exports; yet in stark contrast, 33 million people are currently suffering from food insecurity.

Despite the right to food being enshrined in Article 6 of the Brazilian Federal Constitution, “Will I be able to eat tomorrow?” has once again become a question asked by millions who suffer in violent anonymity.

In Brazil, currently one in four people are either homeless or in inadequate housing. This fact, while shocking, is largely ignored by the country’s government and has been exacerbated by the global economic crisis and the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Misdirection of blame and state inactivity

When I was a child, my parents always told me to be careful with the “homem do saco”, homeless people who collected garbage. There is a whole mythology of fear about homeless people. In this case, the legend talks about a “scary man” who kidnaps children and puts them in rubbish bags.

This attitude betrays the false equation that has always been considered true in Brazil: if you are miserable or homeless, then you are dangerous. In Brazil, people who have experienced homelessness are blamed for their situation by communities around them. When in fact, blame lies with the inactivity of the state and in the ignorance of those who refuse to acknowledge this.

Within this context, Jonathas aims to promote a radical transformation of our communities, and a reimagination of what true mutual aid should look like.

“I want to believe that it is possible to make art as a place of meeting and not segregation,” Jonathas explains. “I could make a film about flowers, but dammit, Brazil is back on the poverty line, back on the hunger map, people are there in the middle of the street… it needs to be talked about.”

The use of warm colours in the film’s photography and the close-up shots of people’s faces reinforce the joy and individual personality of each person in the film. Through this, Jonathas explains that he aimed to underline the lack of humanity that the public normally affords people who experience homelessness.

Jonathas explains his own experience and journey towards confronting the realities of homelessness: “We live in violent cities and too often fear is directed towards those who experience homelessness. A decision not to make this film would have continued this attitude. It would have contributed to maintaining a pact of invisibility and silence.”

By forcing the viewer to confront these questions, Out Loud acts as a direct call-out to those who try to ignore issues of unhoused people and homelessness in their own communities.

Jonathas goes on; “People can be fantastic and fascinating, but they should not be treated as ‘other.’ If we are afraid of people, we make them invisible. It’s a very sad reality about capitalism and a society that prioritises those who have, over those who don’t. It’s a society that excludes.”

Together, we specifically talk about the changes we have seen over the past four years under Bolsonaro’s rampant regime of capitalism, which saw our government cosying up to big US corporations at the expense of both the environment and the already marginalised groups in Brazil.

Fortunately, the (third time) newly elected socialist president Lula has other plans. He’s facing the homelessness crisis head on, with a focus on unhoused populations in São Paulo, the richest city in Brazil.

And while this state action is a welcome step in the right direction, Jonathas believes it is still pertinent to show the realities and give agency to homeless populations to tell their own stories; to show that they are not just a problem to solve, but instead a community of real people who have the right to experience joy and dignity.

Art imitating life

Film can create connection: as it moves, its image helps to make social reality visible. But when that reality is one of poverty and deliberate marginalisation, it begs the important question: how do you responsibly represent marginalised populations on screen?

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

“It’s a very ethically challenging project,” says Jonathas. “I’m aware of the risks and how easy it might have been to get the tone wrong.”

Out Loud seems to reveal pathways for the construction of a dignified and powerful representation of people who are historically represented negatively. There are multiple ways in which Out Loud does this, but what struck me first is how this was constructed through a sense of place.

Because of Jonathas’ use of close-up camera angles, I initially thought that the people in the opening scene were in a forest, not a square in the city centre. This otherworldliness was reflected through the non-naturalistic way that people were organised in the frame.

This estrangement manages to shift the film away from the factual and the pre-existing biases and perceptions that come with this, to bring it to a more creative space – allowing both Jonathas and the people in the film more freedom, and with that, an increased level of authenticity.

Connected with Jonathas’ collaborative approach to filmmaking, this made for a more representative piece of storytelling. Jonathas explains: “I wanted the camera to allow people to shine.”

The happiness and lightness of the encounters seems to be the key to achieving this glow: by breaking the common expectation of associating sad feelings with the marginalised population. “If you are watching this video, remember I’m a person,” one woman says in the film. “You don’t have to look at me with pity in your eyes. Embrace me. Welcome me.”

The path that Jonathas sought in Out Loud seems to be a representation rooted in the humanity of each person he encounters. The connection between viewer and subject happens not because of their state of misery, but to stimulate empathy and connection.

The field of Brazilian cinema and its Black stereotypes

Brazil’s history as a country born out of slavery continues to inform our current realities and inequalities. The country has never reckoned with its violent past and once slavery was finally abolished in 1888, there was no state policy for assimilation of the newly freed Black community.

Instead, these communities found themselves in vulnerable living conditions, a legacy which still exists today, evidenced through the disproportionate number of Black Brazilians who currently experience homelessness. In fact, 70% of Brazil’s homeless population is Black.

This social inequality is replicated in the film industry. The history of Brazilian cinema reveals the tensions and consequences of white and middle-class filmmakers portraying poorer Black people. To give you an idea, I only got to know Black references in cinema after finishing my degree in Journalism. As a Black child, there was hardly any representation of kids like me. I grew up wanting to be like Harry Potter and other white characters in the Hollywood world.

While films possess the power to challenge social norms, they are often a reflection of the society in which they are made. With this in mind, we can assert one factor: the regularity in Brazilian cinema of Black men and women playing the roles of servants and thugs. This is because Black narratives are overwhelmingly told by white authors.

Renowned films like City of God (2002, Kátia Lund and Fernando Meirelles), or Rio, 40 Graus (1955, Nelson Pereira dos Santos) are examples of that complex discussion.

We would be remiss however not to mention obvious examples which break this mould. The classic Alma no Olho, released in 1973, by Black director Zózimo Bulbul is one example which challenges this and offers alternative representations.

There have also been seminal roles played by Black actors which revolutionised the way Black people were seen in Brazil – and prove the sheer importance of representation in film. This was true of Grand Otelo when he played Moleque Miro in Também Somos Irmãos in 1949. The film was one of the first Brazilian films to address the topic of racism.

However, we must still address the question of how to deal with the need to educate viewers on the reality of inequalities and racism, whilst also increasing representation and producing more positive narratives on screen for those from marginalised communities?

Portraying Blackness in Out Loud

With this context in mind, as a white man, Jonathas was hyper aware of his portrayal of Black people in the film. To stay away from canonistic and racist portrayals, Jonathas opted for a more creative path, using collaborative practice through spontaneity and open dialogue with the people filmed as two main elements in the production of socially relevant art. As a result, he says,: “the unrehearsed moments of the film became its main scenes”.

“Initially, the film was going to be a choreographed production with dance and music,” he tells me. “But during the first hour of filming, someone came up to me and asked: ‘when do I talk to the camera?’ By the time the fifth person had asked the same question, I realised I needed to go in a different direction.”

The people who were going to be the subjects in his film had a story to tell, and it became clear to Jonathas that it was necessary – both for the film and the people who were being filmed – for there to be open and non-hierarchical dialogue.

“Those who experience homelessness are so often not listened to. I wanted people to use the film as a chance to make their voices heard; to harness their power, as a platform to tell their message to the viewer. It had to be rooted in collaboration.” For me, it’s visible how much Jonathas’ openness to listening to the film’s characters has evolved into a less fetishized and more human representation of the homeless.

The making of the film

Filming for Out Loud took place over two consecutive days. To find the cast, Jonathas approached social workers, NGOs, public shelters in Recife and places where free food distribution took place.

“It was a process of having conversations in the shelters, announcing the film and its intentions and inviting interested people to come and be photographed,” he explains.

For Jonathas, Out Loud can be summarised as an exercise in the gaze. “I believe art is a place of invention, creation, pedagogy and learning. If we’re going to talk about pain, let it be bright with possibility.”

He goes on: “Making the film was a learning process for me and I hope it will be for the audience also. I want it to act as an invitation to look at people who are experiencing homelessness not as a faceless mass, but rather as individuals.”

After watching Out Loud, I came away with hope. I can now say that there’s another filmmaker in Brazil who is forging a possible path for the production of a cinema that celebrates the humanity of racialised and marginalised people, rather than reproducing the same systems of marginalisation.

Fortunately, in 2023, we have a new government whose motto is “union and reconstruction” and many of us are filled with optimism of a brighter Brazil.

We hope that this will put Brazil on the path towards better access to housing, food, dignity, leisure and health. We hope that a time will soon arrive when Brazilian cinema only serves to remember the hunger of the past, and not produce denunciations of an irresponsible government and a suffering people.

What can you do?

Watch:

- Jup do Bairro – O CORRE (Official Music Video)

- Céu – Rapsódia Brasilis (Álbum Tropix) [Áudio Oficial]

Listen:

Read:

- Before the Mayflower: A History of the Negro in America, 1619-1962 by Lerone Bennett.

- Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Man by W E B DuBois.

- Slow Fade to Black: The Negro in American Film, 1900-1942 by Thomas Cripps.

- Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media by Ella Shohat and Robert Stam.

- Tropical Multiculturalism: A Comparative History of Race in Brazilian Cinema and Culture by Robert Stam.

Read more articles about Brazilian politics on shado: