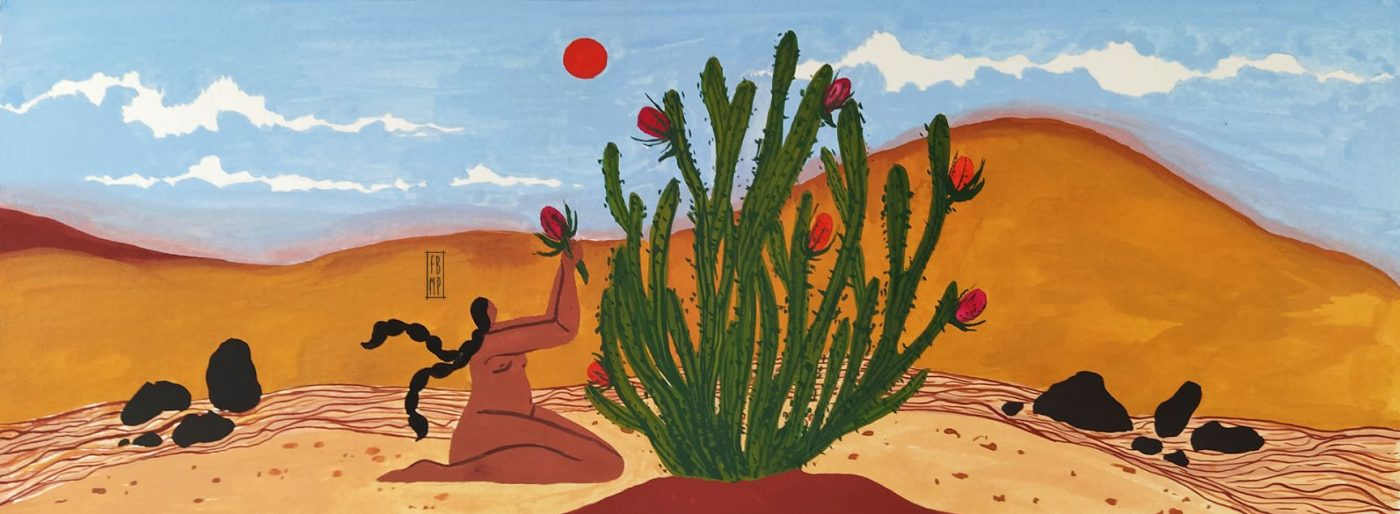

The Caatinga, whose name has its origins in the Indigenous Tupi-Guarani language and translates to ‘white forest’, is the only biome exclusive to Brazil. Around 70% of the Caatinga is located in the Northeast of Brazil, and due to its unique subtropical climate, the wildlife has adapted, meaning that many distinctive flora and fauna exist there.

Government neglect

However, this region was the first to fall victim to Portuguese colonisation and has since been continuously neglected by Brazil’s policymakers, which has left this wildlife under extreme threat.

Indeed, because the Caatinga is seen to be poor in biodiversity, the region rarely receives any investment for conservation purposes. Being drought-prone, it is also particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

Part of the problem is that many people think the Caatinga is a just a desert, without traditional communities or fertile land – and ironically, due to its colonial legacy combined with urbanisation and continued deforestation, this could soon become a reality. But to keep our house alive, we need to realise that the Caatinga can be a thriving landscape if it is allowed to be protected by its Indigenous communities. Unless we honour their customs, the Caatinga and its people will disappear.

Stewards of the land

Historically known for their cultural, linguistic and environmental caretaking role, the native peoples of Caatinga have always been the best protectors of the biome.

Sônia Guajajara, a leader from Maranhão state, explains why: “The land, for each one of us, is much more than a small piece of negotiable space. We have a spiritual relationship with the land of our ancestors. We don’t negotiate territorial rights because land, for us, represents our lives. The land is a mother, and a mother cannot be sold, cannot be negotiated. We care for, defend and protect our mothers.”

A history of persecution

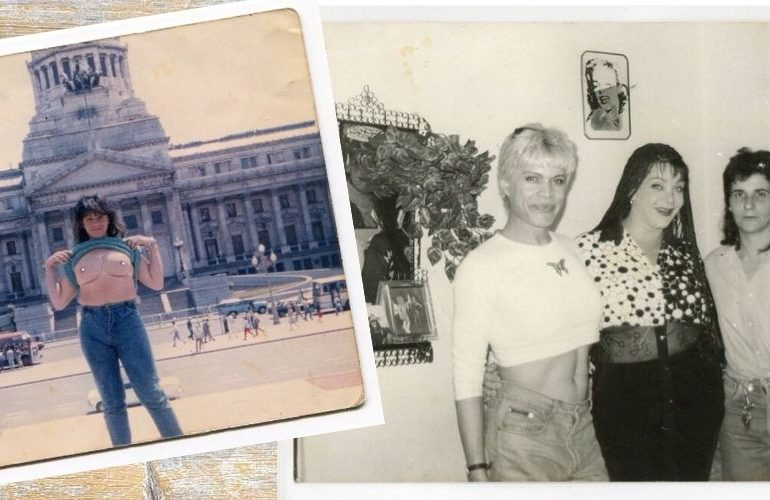

In spite of this, Indigenous people have endured a history of persecution. Instigated by Portuguese colonists, native people throughout South America have been systematically persecuted, enslaved and stripped of their culture. This extensive exploitation continues to marginalise Indigenous communities in Brazil. Today, our guardians of the environment continue to suffer from the threats of harmful extractive activities, including mining, demarcation of land for industrial and business purposes and deforestation in its various forms.

This exploitation is not just felt by those in the Maranhão state, but appears to be a collective experience across the region. Hamangaí Pataxó, an Indigenous woman from Cruz das Almas, Bahia, tells me about the history of her people, the Pataxó Hã-Hã-Hãe, and how extraction and land theft in the Caatinga has impacted their lives.

Struggles for land sovereignty and self-demarcation

“We have an extensive history of colonial exploitation of our territory and the violation of our rights to the land,” she explains. “In the struggle for the demarcation of the territory, several leaders were brutally murdered, such as Galdino, who was assassinated in Brasília in 1997. With the delay in the trial and the increase of violent conflicts against our people, the community decided, in an autonomous and organised way, to carry out the process of self-demarcation ourselves, thus turning our story into powerful proof that territory can be won back.” This process of demarcating the territory was finally ruled in 2012, and the Pataxó Hã-Hã-Hãe people were victorious in the Supreme Court.

The lasting legacies of exploitation and extraction

But, Hamangaí continues, “Even with the demarcated territory, the challenges and problems have only increased, with lasting problems such as access to drinking water, education, and health continuing to affect our communities.

Hamangaí further explains that “the elders of our village imagined that with the demarcated territory, all of our problems would end and we could live peacefully in the community. However, we are now faced with the lasting effects on the land – a large part of the territory was deforested for cattle raising and cocoa planting by farmers. This has degraded the land over the years and today several springs and rivers no longer exist.”

The illegal sale of wood is also a major concern for the Pataxó Hã-Hã-Hãe people, as this has caused the disappearance of a number of native trees and animal species. Hamangaí explains, “there are several initiatives in the community aimed at the protection, environmental education, and reforestation of these areas, but there is a lack of resources and support for these activities.” All these problems reflect the State’s disregard for the traditional communities of the Caatinga and threaten their survival and the maintenance of their territories.

Impacts of COVID-19

This dismissive attitude towards the Caatinga has directly affected its inhabitants. The Pataxó Hã-Hã-Hãe people were one of the many Indigenous groups disproportionately affected by COVID-19. They not only suffered high mortality rates but young people in the village were left without access to education as no provisions for online learning were made.

Hamangaí also talks about the scrapping the postion of SESAI (the Special Secretariat for Indigenous Health), as proof of the lack of commitment from the government to protect the health of Indigenous people, explaining to me that this attitude was “tantamount to genocide.” In response to this, in October 2021, the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples from Brazil (APIB) filed a petition with the Supreme Court requesting the strengthening of immunisation for all Indigenous peoples. It has not yet been approved.

Self-determination and political representation

The peoples of the Caatinga need resources to overcome their difficulties and to survive the drought and other problems that are killing their territories. Hamangaí is fighting for her community rights – she and other young Indigenous people are an example of resistance and courage, who are defending their lives and their villages to protect the environment and humanity.

Talking to these land defenders proves the need for governments to listen to Indigenous peoples and allow them to occupy educational and media spaces. Society needs to leverage practises that preserve the environment and denounce any activity that may degrade it. With strength, resistance and resilience, the Indigenous peoples of the Caatinga can continue to live, reclaiming their territories and their cultures.