Trying to decide on the best opening for this article, I was alternating between two quotes. My first option was: “Saints belong to the people.” The second: “Accumulated sperm is very bad for the body.” Both of them are quotes by José Pérez Ocaña, and both are taken from the documentary Ocaña, an Intermittent Portrait, offered as the centerpiece of the exhibition Ocaña. Der Engel, der in der Qual singt, which opened in Berlin’s Schwules Museum this May.

Ocaña was a performance artist, a painter and a papier-mâché sculptor, occasionally even an actor; in sum, one of the key figures of the 1970s Spanish counterculture.

Altogether, it is admittingly quite a small exhibition, but still a very important step – and hopefully not the last one – in the re-evaluation of Ocaña’s artistic oeuvre.

In the end, I decided to open the text with both quotes, as together they best summarize Ocaña’s approach to life and his artistic output, marking his strong investment in religion and spirituality on the one hand, and transgressive sexuality on the other. Moreover, the two quotes announce a fundamental ambivalence at the very heart of his art, an ambivalence which, I believe, has largely to do with the third category through which we ought to approach Ocaña (and which was, unfortunately, absent from the exhibition framework): the question of class.

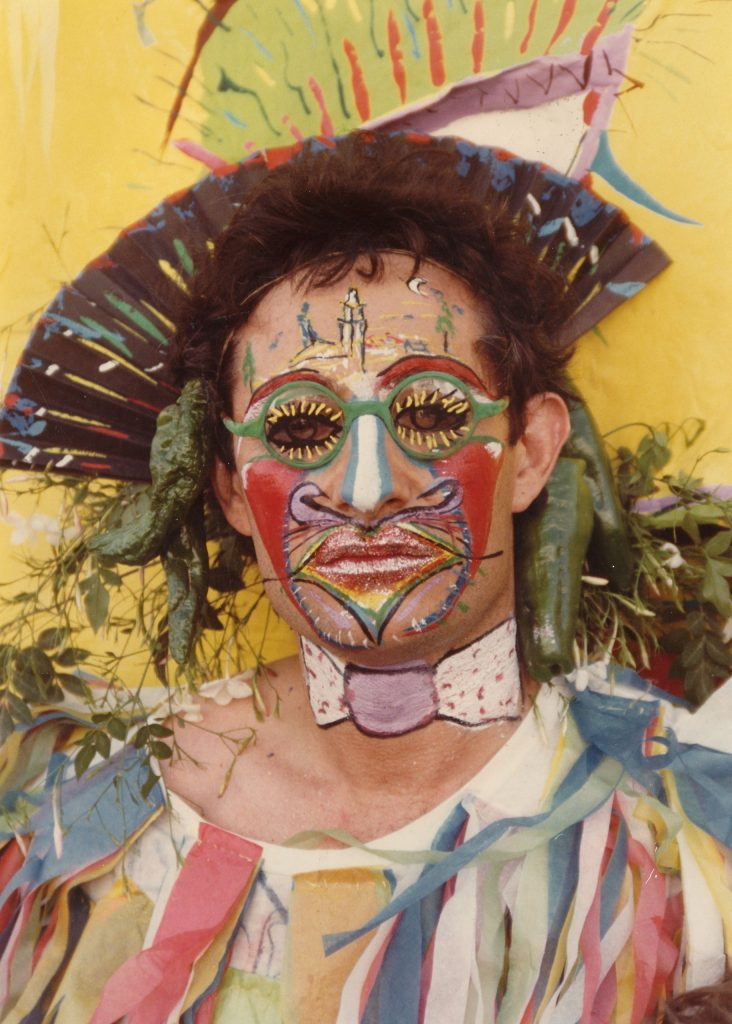

Although Ocaña was working with different media and art techniques, the most significant among his artwork are his public performances.

The most famous is Der Engel, der in der Qual singt (“the angel that sings in agony”). This very rich and playful performance in Berlin in 1979 features Ocaña speaking with a cardboard cutout of Marylin Monroe.

At one point, he explains to Monroe that, while she, as a woman, was an object of consumption, Ocaña is a marginalised woman. With this characteristically vague assertion, he establishes a connection between the two figures of femininity, while at the same time drawing a clear demarcation between them. Although both of them inevitably suffer in their respective heteropatriarchal societies, the poor Andalusian woman Ocaña is performing here, is miles away from a US pop icon. Moreover, the very fact that Ocaña assumes a position of a woman in the surrounding that still sees him as a “cross-dressing” man, adds another layer here. It is this playful take on different types of displacement – that touches both on gender and class – that comes as crucial in Ocaña’s art in general.

However, I find his interventions in public space, which often seem more as Ocaña’s spontaneous engagement with everyday life in Barcelona, rather than professional performances, much more interesting.

For example, the exhibition features a video of Ocaña walking down La Rambla, dressed in traditionally feminine clothes, occasionally flashing his genitalia, while random passengers, of all genders, follow him with amusement and excitement. We then see him, still dressed as a woman, grabbing a trolley with a small child from a random lady, who seems both confused and delighted by what is happening.

Even from today’s perspective, I could not help but be deeply impressed by the ease and simple unapologetic pleasure with which he does all of this. The freshness, the contemporaneousness of his art with our times is simply astonishing.

Ocaña’s playful take on religious rituals and Christian iconography follows a similar brave suit, but is possibly more elaborate.

Ocaña and his friends, dressed as somewhat extravagant nuns, re-enact religious street processions, a very important ritual practice in Catholic Southern Europe. While walking the streets, they hold colorful papier-mâché sculptures of saints and divinities made by Ocaña himself. The most important sculpture is that of the Divine Shepherdess of Cantillana. This is Ocaña’s tribute to, or rather, an attempt to stay tied to, his small hometown of Cantillana in the Andalusian province of Seville.

Ocaña had to leave Cantillana for bigger and, as he himself says, more liberal Barcelona, because he was mocked, attacked and even stoned for being openly gay.

However, he never cut ties with his homeplace. Even when recounting this terrible story of violence, Ocaña finds a Biblical moment to relate to, comparing himself with the story of Mary Magdalene.

Therefore, what is most impressive in his performances inspired by religious rituals is a certain mixture of appreciation and blasphemy, but blasphemy that never crosses towards mockery, or dismissal of spirituality and religion.

On the contrary, the blasphemy here consists in opening up of this very spirituality, together with its religious rituals and Christian aesthetics, to yet another marginalised group: the transgressive ones, cross-dressers, drag queens, queers, maricones. Indeed, saints do belong to people.

As it is clear from his art and his interviews, Ocaña maintains a critical attitude towards Catholic Church as the oppressive institution, and yet holds a strong appreciation of, as he calls it, Christian fetishist aesthetics. Therefore, one of the crucial moments in Pons’ documentary is Ocaña’s clear annoyance with leftist intellectuals that are attacking people for their naïve beliefs and ridiculous rituals. “If you take this from them,” he asks, “what are they left with?; Do not take away people’s fetishes!”

This brings us to possibly the most important aspect of Ocaña’s artistic existence – his closeness to “the people.” This is not just because he comes from a working class background (his parents were a bricklayer and a dresser), but also because, even while pursuing his passion for arts, he continued working as a house painter for the rest of his life, as the money he would get from his artwork could not cover the bills.

It should also be mentioned here that one of his most iconic performances – also recorded on video – that ended up in him taking his dress off, happened during the Workers’ Party assembly.

As we can see, this closeness to the masses, to the everyday lives of people that surround him, was a very important part of Ocaña’s public performances. Indeed, we might even say that what is most transgressive about his art is not the fact that it includes elements of what can be perceived to be religious blasphemy and gender and sexual provocation. After all, the visual and performing arts of the late 20th century, including Franco’s and, especially, post-Franco’s Spain did not lack in these kinds of practices.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

In other words, we can easily relate Ocaña’s performances to the Destape (literally: “undressing”) film movement of the 1970s Spain, as well as, more broadly, to the punk culture and the emergence of what we nowadays call queer culture in parts of the global West. Therefore, what is most transgressive in Ocaña’s approach to art is the very fact that every transgression he did, he did for the people, in front of the people, taking into account the shared culture he also belonged to.

We can see the same artistic ethos when it comes to his paintings, both on the conceptual level and on the level of style. Ocaña was operating outside the artistic establishment. He did not dream about exhibiting his work in museums, but about exposing his paintings and drawings in the streets, so that everyone can see them.

The content and the style of his paintings also easily communicate with the masses, as he was inspired by Andalusian folklore, very much immersed in religious imagery; he saw Andalusia as a surrealist painting. Ocaña was a self-thought, naïve artist, and this clearly shows in his paintings of rural life, with angels and saints, all of them very rich in color.

Unfortunately, all of this remained mostly unnoticed during Ocaña’s life. He was very resentful of the fact that his paintings were almost completely ignored by the media of the time, and that his art was being almost entirely reduced to the “scandalous” habit of his so-called cross-dressing.

In this sense, we might appreciate or even celebrate the fact that some of Ocaña’s drawings and paintings today hit €1,800 on Todocoleccion , an online auction website based in Spain. However, we ought to keep in mind that his idea was actually always the opposite: everyone should be able to enjoy his art.

Therefore, more than his higher monetary value, we should appreciate that, finally, Ocaña is being reclaimed as one of the first “queer” artist by the younger generations in Spain. Recently, a play based on his life and arts was staged in Barcelona.

Perhaps more importantly, sheerily by the scope of its influence, one of the contestants in the most recent season of Drag Race España paid a tribute to Ocaña, the Queen of La Rambla. Hopefully, this announces more thorough re-evaluation of Ocaña, both in Spain and outside.

Once more: saints do belong to people. Indeed, Ocaña might as well be one of them, and he belongs to all of us.

What can you do?

- Watch Ocaña’s 1979 performance in Berlin:Ocana der engel der in der qual singt (1979) by Gérard Courant

- Watch Pons’ documentary: Ocaña, Retrat Intermitent Retrato Intermitente Angee Para Zoowoman : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming

- Read an entry on Ocaña from the lgbtq Encyclopedia Project: Ocaña, José Pérez (1947-1983) – by Linda Rapp

- Join the sisterhood of Blessed Ocaña: HERMANDAD DE LA BEATA OCAÑA