Like most public events in Sudan, the current wave of protests is accompanied and accelerated through artistic means. In the 30 years of President Omar al-Bashir’s military dictatorship, there has never been a civil uprising comparable to the one that has been shaking the country since 19th December 2018. The artistic expressions that are part of and artworks that have been documenting these protests are novel in their intensity and content. There has been a long history of the use of political cartoons in Sudan since the 1950s and artists learned to continually adapt to different political environments.

During authoritative rules, artists resorted to self-censorship and communicated their political messages subversively to supersede censorship and prosecution. Those who didn’t obey those rules suffered consequences. This is still the case today, but

the digital realm has opened up another universe of opportunities.

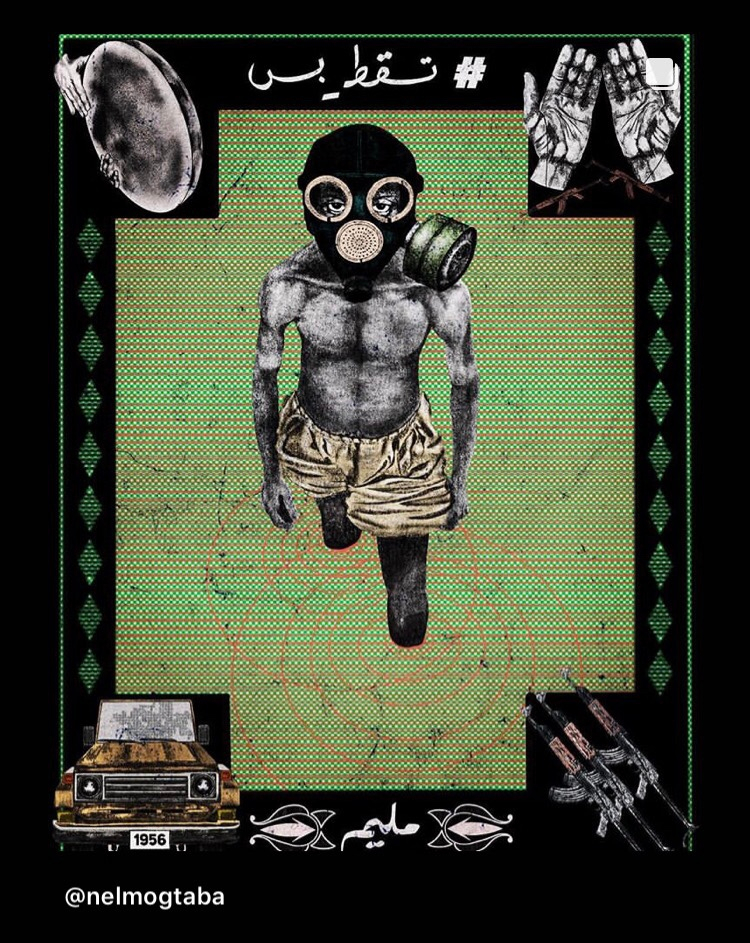

Traditional media channels including radio, television and newspapers fail to provide a forum to discuss political issues due to confinement imposed by the government. Social media has become not just a tool for communication but an outlet for greater freedom to express political opinions, in the forefront of all this is the Sudanese Professional’s Association. In the past weeks, Instagram has exploded with artistic productions from Sudan and the diaspora.

Virtual public spaces have given artists and activists alike the chance to voice opinions on a global platform while having the option to stay (semi-) anonymous without fear of persecution.

They have also provided the opportunity to those in the diaspora (or otherwise unable to march in the streets) to participate in the civil uprising.

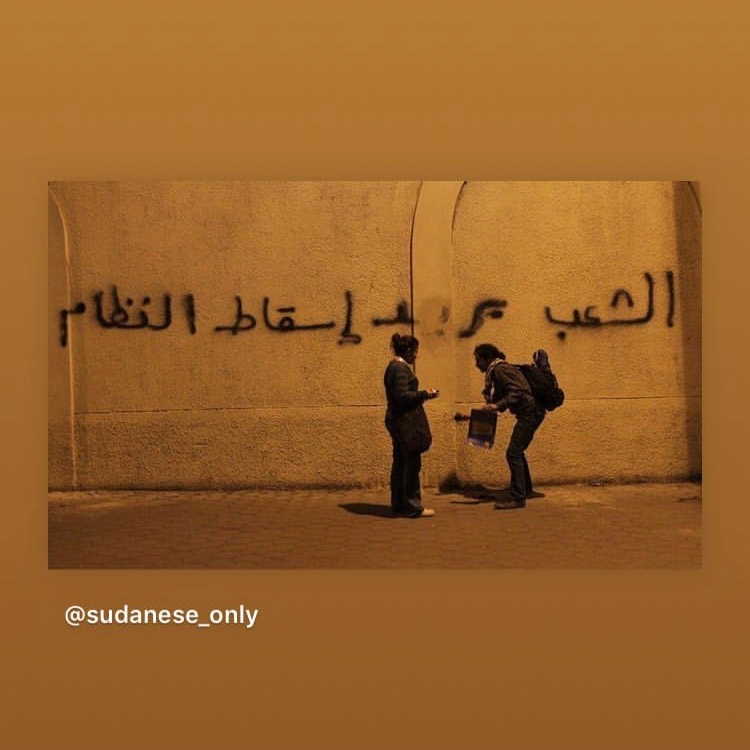

Sudani Twitter with users in Sudan and the diaspora is filled with (graphic) audiovisual content exposing the violence that the peaceful protestors from Atbara to Ghaybesh are met with while chanting “حرية سلام عدالة” (freedom, peace, justice). The hashtags مدن_السودان_تنتفض# (Sudan’s cities uprising) تسقط_بس# (just fall) and #sudanrevolts are a way to mobilise the protest culture and fuel discussion. Those documenting the protests and the ongoing human rights violations are a thorn in the eye of Sudan’s ruling elite who have cut access to social media. Anonymous reacted to this by attacking official websites and archiving audiovisual proof for the state’s violence. Artists appropriate iconic images – which, in many cases, increases their shareability and global reach. A clear example of this is the arrest of a protestor on a boxi (pick-up-truck used by the police and National Security/Intelligence Service) still holding the Sudanese national flag up in the air while lying on the back of the car.

More disturbing details are coming out concerning the detention of thousands of (non-)political actors who have been picked up from the streets and from their own homes by police and security forces on a daily basis – not to mention those killed through torture and live ammunition.

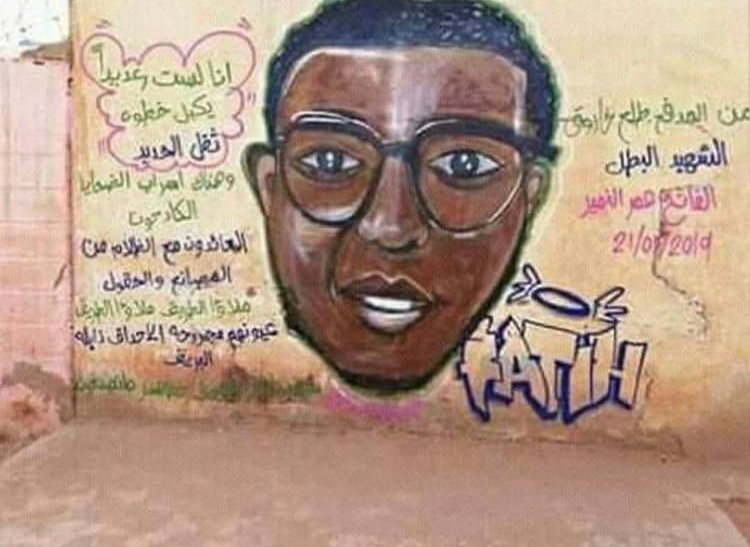

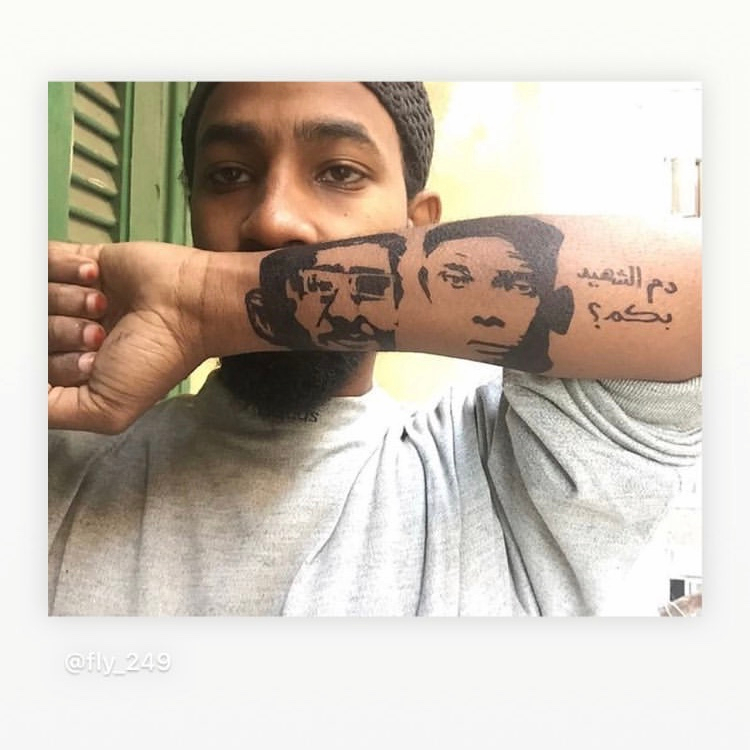

Artists have been documenting this through depicting snapshots of events and portraits of victims. Amani and Samir, two protestors who were attacked by the police, lost their eyesight and became icons of the bravery, strength and endurance of the people demonstrating in the streets. Artworks honouring them have been widely circulated. Another protestor who has become frequently portrayed is Mohamed Al Masri, who lost one of his hands during the protests in December but nonetheless was seen marching in the streets again in January.

The government has responded to the deaths of protestors by claiming that other people are responsible for these casualties.

Government forces even detained a donkey that was marked creatively with a protest chant mocking the government.

This moment, recorded on camera, presented a perfect occasion for artists to mock their procedures even further. Meanwhile al-Bashir stated that he is satisfied with the executive forces actions.

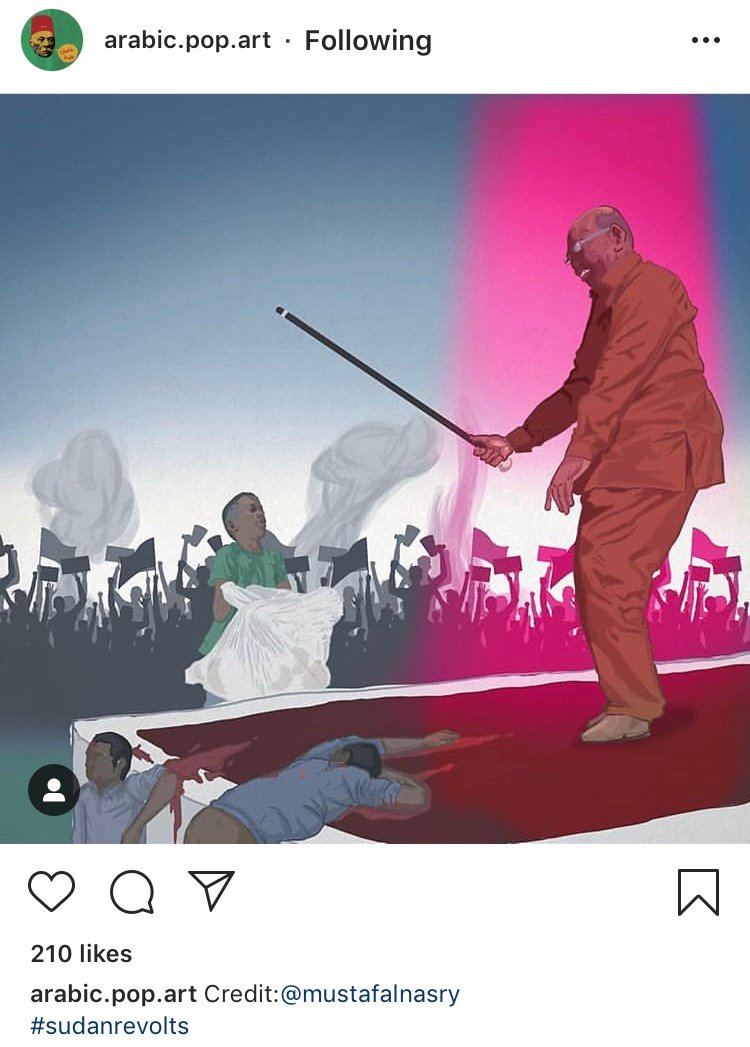

In the midst of all the accusations of human rights violations, Bashir held a pro-government ‘1 Million People March’ at Green Yard, dancing on stage in front of governmental employees. Concerning the online protests, he said, “Changing the government or president cannot be done through WhatsApp or Facebook. It can be done only through elections.” While this spectacle took place, his security forces were teargassing peaceful anti-government protestors. The hypocrisy of this motivated many responses from artists.

Although portraying the President is punishable by law, fear of doing so has dramatically decreased in light of more and more people joining the protests. Social media platforms are full of caricatures of Bashir which depict the oppressive system he and his government have installed for the past 3 decades.

Street art is another vehicle of resistance in Sudan’s protest history; a medium of voicing political opinion which has spread all over the urban centre. Simple slogans reiterate the tenets of the movement while portraits of the martyrs enhance the community’s unity. Under the cover of night, activists spray their messages on billboards and walls all over Khartoum, while protest posters appear at traffic lights. The non-violent resistance movement Girifna became is well known for its use of street art in highlighting their protest.

While police and security forces shoot rubber bullets, gas canisters and live ammunition at protestors, some collected these items. On one hand, this can be used to prove the violent backlash they face – on the other, it can be used to contest the violence through artistic means. Tear gas canisters are laid down on the ground forming words such as names of neighbourhoods, or protest chants like تسقط_بس (just fall). Bullets have also been used to create jewellery.

These appropriations of ammunition contest the power of the ‘enemy’ and send powerful messages of resistance and resilience.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

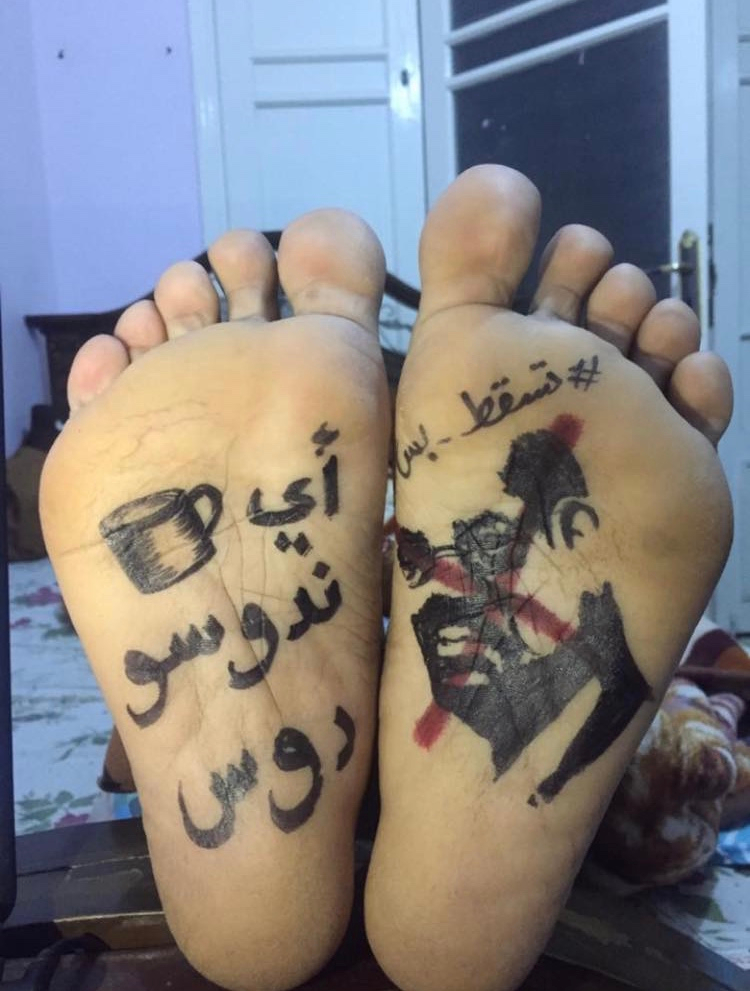

The role of women has been vital in the current uprising. One example is a new practice undertaken by women, in which they write anti-government slogans on their hands and feet with henna – which is traditionally used to decorate women and show their marital status. Using henna as a form of protest is an act of dedication to the cause, and puts them at great risk in public spaces where their political commentary becomes publicly visible. Similarly, male artists have been appropriating the henna tradition, using permanent markers to inscribe chants, flags and faces onto their skin.

Protest art has become a self-perpetuating movement. The artistic expressions, deeply rooted in the moment and space in which they originate, represent the creativity of the Sudanese people to develop new tools for protest, as well creating a dialogue that is stronger and longer-lasting than the tyranny of the ruling elite. The artworks provoke the government to respond with acts of cruelty, but these only increase the resolve of the artists. The struggle is still ongoing and we are yet to witness the full change that is on its way.