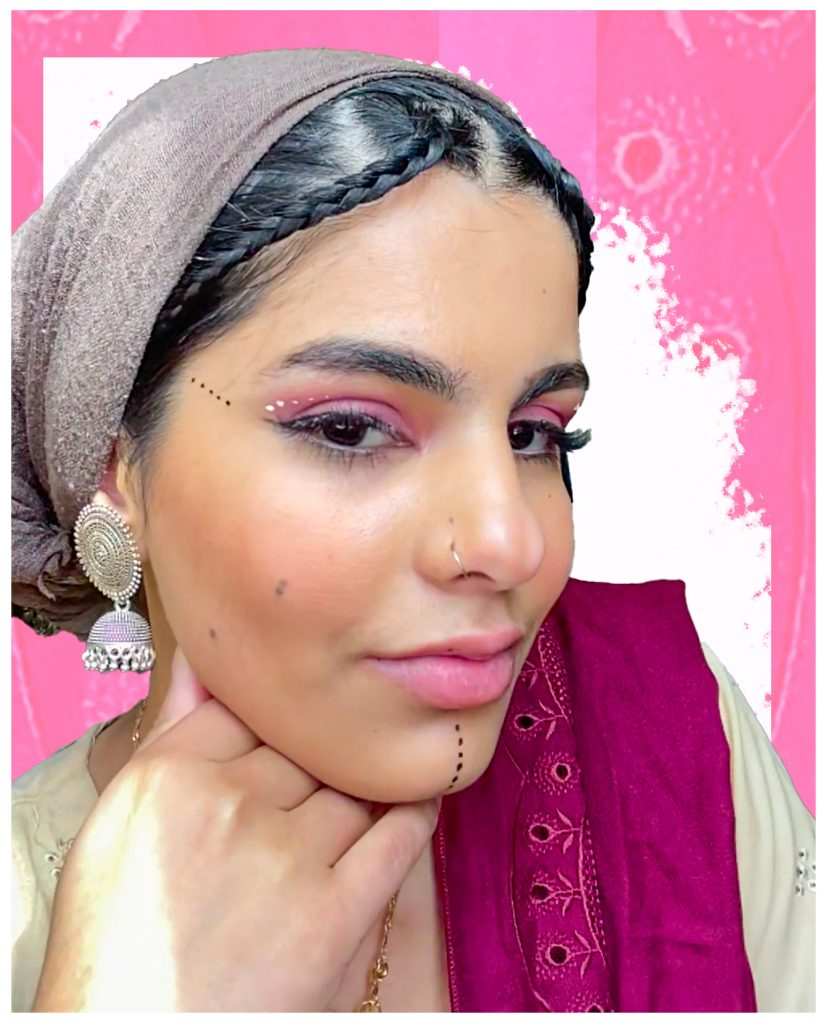

Ayisha Siddiqa – organiser, speaker and poet – was at the heart of mobilising the 2019 climate strikes in New York. You might remember the photos: over 350,000 people went on strike across the US, setting records for the largest protests since the anti-Vietnam demonstrations decades before.

Ayisha, fresh from student protests on a smaller scale, was thrown into collaboratively organising this mass demonstration in the lead up to the 2019 UN New York Climate Summit.

“Vanessa Nakate was there, Greta Thunberg was there. World leaders were flying into New York,” explains Ayisha. “It was a beacon of change that we could hold onto. Finally, a way for those of us in affected communities to put our demands in front of a leader.”

But the beacon quickly dimmed. Comrades from other countries couldn’t enter the US as Trump’s ‘Muslim Travel Ban’ was in full effect.

The highly necessary voices of Global South activists were denied visas by the US government. A promising youth summit, which Ayisha hoped would provide a meaningful platform, turned out to be “one of the most patronising events she’d ever been to.” Barred from meeting with decision-makers, it became clear the conference was at best a platitude, and at worst a PR move.

“They had training on how to use iMovie, and paparazzi were in the mix. People who were being directly impacted by climate disaster had travelled across the world to be there, only to be treated as completely incompetent.”

Despite the enormity of the strikes, the formidable youth movement was not being taken seriously. “We were looking at each other like: are we even doing anything that actually affects the status quo? Because if they’re not threatened by us, then we need to urgently shift our ideology.”

And then COP25 happened.

2019’s iteration of COP, the annual UN conference where leaders get together to negotiate international climate policy and action, was notoriously horrendous. “Indigenous people were physically pushed from negotiations, peaceful campaigners were kicked out of the space. All the while, the CEOs of Shell and Exxon were roaming freely.”

That was the final straw for Ayisha, and her BIPOC comrades. “The whole point of the conference, which began in 1998, was to bring world leaders together to put measurable steps in place to mitigate carbon emissions.”

“It’s been 25 years, and this change hasn’t happened. Why? Follow the money. The money to host these conferences comes from the fossil fuel industry. COP25 was bankrolled by Ibrerdrola, one of the biggest polluters in Spain. And in the hundreds of pages that make up the Paris Climate Agreement, the term ‘fossil fuel’ is not mentioned once.”

It’s not at all subtle, and it’s a major conflict of interest. That’s why we started Polluters Out.”

Polluters Out

Polluters Out is a youth-led global coalition of grassroots movements aiming to address the prolonged issue of the fossil fuel industry’s control of every aspect of society from Indigenous lands, governments, banks, universities, and climate negotiations. But Ayisha, having been burned before, took her learnings from COP to form the bedrock of her new organisation.

“The youth climate movement in the US were still not saying the word fossil fuel explicitly, or calling out oil companies. And the abstract demands of a ‘climate emergency’ were just leading to empty platitudes. Our demands were measurable and achievable, and we went to institutions like the UN that could meet them.”.

And the precedent had already been set. “The largest lobby used to be Big Tobacco. They would go to the World Health Organisation conferences every year, pushing their products and offering alternative theories for why people were getting cancer.” After pressure, the World Health Organisation signed a conflict of interest policy to end the tobacco industry’s influence. “And since then, we’ve seen an almighty cultural shift in how tobacco is consumed,” Ayisha explains. “The penalisation wasn’t just rhetoric, but actually led to taxation and prevention from influencing decision-making spaces.

So Polluters Out is just following this example.”

But what happened to the youth movement?

The work is damn impressive and necessary. But as someone who was organising in parallel in the UK, I ask Ayisha about the youth movement that was at its peak in 2019, and which elevated her into the international space. Where is it now? Is it COVID-19? Mass burn-out?

“The youth movement did wonders. It brought climate into public discourse, it brought it to every election in the world. But we’re at the point where we need to acknowledge that the “Western Youth climate” movement is not fluctuating, it’s dying.

It was reliant on the heartstrings of the Global North. It asked people to care for their children first, hoping that it would make them care about the world. It paved the way for personality cults over community organising.The whole discourse around ‘saving our futures’ felt problematic to me.

“I never had the word climate change in my vocabulary. Growing up in Pakistan, I knew bombs and drones. We didn’t get to think about futures. Children’s entire lives were already being destroyed by the oil industry. My people became refugees and were met with xenophobia and prejudice. No one thought about our future or about the right for the Global South as a whole to have a future. The movement that gained popularity in the global North was not made to protect Black, brown, Indigenous people and it is so odd to me that over the years it has built its foundations on our struggles.

The youth movement initially worked because a blonde-haired, blue-eyed child could pull on those heartstrings with a rhetoric around futures. It needed someone who looked like the status quo to make the status quo care – because it reminded them of their own vulnerability.” And we’ve seen the same rhetoric from western countries outpouring their solidarity to Ukrainian resistance in the past few weeks – a response not granted to the conflicts in Syria, Iraq or Afghanistan.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

The Fridays For Future model wasn’t political enough – because how could it be? The model had to work in every country.”

Youthwashing

“I saw before my eyes, campaigners as young as 13 being offered platforms and opportunities by governments, philanthropy groups, and businesses.” This is a term known as youthwashing, where young people are tokenised to legitimise a business or organisations activities – like Shell’s Make the Future campaign. Another pertinent example is Samsungs ‘climate superstars challenge’ working with school age kids on environmental projects, all while they were facing backlash over their involvement in building a coal-fired power plant in Dubai.

“And if you’re 13, and you don’t have anyone telling you otherwise – you’re going to say yes to these platforms. And that’s how they co-opted us. Because if you get the people holding you to account to work for you – you subdue and dilute the revolution.

We must be more political now. National histories must be considered. It petered out in the US because climate change is political. America’s foundations and history are built on Indigenous genocide, slavery, and exploitation of Black and Brown people. When a movement that claims to help those very people doesn’t, then it dissipates. Movements must threaten the status quo, or they will fail.

You can become a celebrity in the US just by holding a placard. My friend Disha Ravi from India’s Fridays for Future was thrown in jail for holding a placard. In a country like mine, Pakistan, holding a placard is threatening because that status quo pulls up with weapons to shut us down. Our realities are not the same.”

So where do we go from here? Ayisha took her learnings from COP25 to form the bedrock of her new organisation. “Governments change for the better when Black and brown people come together and ask for change. Black and Brown bodies represent a political consciousness.” Ayisha explains, “We understand protecting the Earth because our histories have been about surviving threat after threat. In this way we are an extension of nature and can understand her pain and what has allowed her to persevere is the love of our people”.

“We can’t let our strength and message be co-opted to further promote capitalist gain that in the long run does a disservice to the safety and existence of our histories and our futures.”

Big corporations are in the business of co-opting radical movements because they know it’s necessary for their survival. They understand opportunity means everything to a young person desperate to affect change, especially in these unstable times where it’s difficult to find a job, buy a house and manage the rising costs of living.

But Ayisha’s learnings from the frontlines of the biggest youth movement in living history show us that when the photo ops and job offers come rolling in, it’s because the system is threatened and we’re doing something right.

In the business of love

You can read Ayisha’s brilliant and beautiful poetry on her Twitter, and her reading reflecting on her experience being tokenised once again in climate spaces “On Another Panel About Climate Change They Ask Me To Solve the Future – But All I’ve Got Is a Love Poem”.

Ayisha tells me how her poetry is resistance in cold and unloving spaces: “I have the land that I come from, and we have been doing this work before there was even a youth climate movement. And we will continue to do this work. It’s part of our existence.”

She ends, “But I’m not in the business of selling the future. Mine is to show and then ask people to make a choice.”

So lessons learned from this insightful conversation with Ayisha? The global north needs to get more political in climate campaigning. We must continue to move away from palatable messaging towards measurable demands which centre justice and Black and Brown leadership – climate reparations over climate action, abolish borders over save the polar bears. The time for the complex work of linking struggles locally and finding ways forward is now. Radical education which teaches young people about how movements become co-opted is essential. Global solidarity is crucial, but independent models of resistance are necessary. None of this is easy, but it never has been!

The louder and more radical youth climate activism is, the harder it is to be co-opted or be used as a tool to legitimise capitalism. Let us centre rage and resistance, but with love and care as well. And truly do check out Ayisha’s poems – they’re food for the angry soul.

What can you do?

- Follow Ayisha and her work and poetry on Twitter and Instagram.

- Sign up to Polluters Out here and follow them on Twitter here

- Read Nature is a Human Right: Why We’re Fighting for Green in a Grey World

- Read Life in the city of dirty water by Clayton Thomas-Müller

- Read shado issue 04: YOUTH

- Check out the Art not Oil coalition who are campaigning to end fossil fuel sponsorship of the arts.

- Educate yourself and take part in Fossil Free Universities 12 week training course.

- Support Lake Victoria campaign follow @rahmina_paullete

- If you are a student in the UK, check out People and Planet who coordinate the student divest movement and check out their latest campaign Fossil Free Careers severing the recruitment pipeline between universities and fossil fuel companies.

- Get involved in your local divest movement here if you are UK based.