Five years ago, almost to the day, standing next to my mum, our trousers rolled up and bare feet in the grey October sea, flashing lights of the Great Yarmouth seafront behind us, I realised I was in a coercive controlling relationship, and that I needed to get out.

Three days earlier, I’d arrived at Mum’s house in Norwich, empty and drained. I had been performing on stage for nine months. I had a couple of weeks off before the production started again, and Mum had suggested we do a long walk together. I hadn’t seen her in months.

When I arrived, she says now, she barely recognised me. Her usually open and talkative daughter was withdrawn and tense. I couldn’t meet her eye. She said to me at dinner, after a long silence: “The light in your lighthouse is out.” I made some joke to deflect – something snarky about bad metaphors – and went to bed.

The next morning, Mum was standing in the kitchen, wearing a waterproof coat and walking boots. There were a pair laid out for me and two small backpacks by the door. “Right,” she said. “Let’s go.”

Mum and I walked for three days along the River Yare, stopping to sleep in whatever B&B had a spare room when our legs were too tired to keep walking, or our clothes were too soaked from the constant rain. We walked through empty fields, along dirt tracks, and across marshland – abandoned windmills the only break in the huge, flat horizon. But I couldn’t relax. My phone was buzzing repeatedly in my pocket. And I had to respond to every message.

Mum and I were distant with each other at first, both talking at cross-purposes, skirting round the thing that needed to be addressed. Her, fearful of me shutting down further. Me, terrified to look at the problem right in front of me. The problem buzzing in my pocket. That aggressive buzz. Continually. For the full three days.

She asked me about him. I changed the subject. Hours later, as we walked past the sugar factory in Cantley, steam billowing from the steel silos across the river, she tried another tack. She talked about one of her past relationships – a relationship that had started out as passionate, desperately romantic, thrillingly fast-moving, but that had become suffocating and all-consuming. She talked to me about friends of hers who had had similar relationships, how she’d watched them disappear, their time, independence, and even finances controlled by their partners. She told me how the signs could be almost imperceptible at first. My phone continued to buzz.

By the time we got to the outskirts of Great Yarmouth, something had shifted. I was ignoring the messages. We passed fish and chip shops and arcades, walked straight to the sea, took off our shoes, and let the waves lap our feet. I’d decided I needed to leave him.

Recovery and research

A year or so later, when I’d begun to talk about the relationship in therapy and was coming to terms with the fact that I wasn’t to blame for his controlling behaviour, I found the subject of coercive control bubbling up in many aspects of my life.

Friends I’d known for years and colleagues I’d met only recently were opening up to me about their own controlling past relationships. I was shocked at how prevalent it was. How pervasive. I was angry too. I could somehow comprehend how it had happened to me, how I’d got myself tangled in an emotionally abusive net – though I was still partially blaming myself for being weak, unseeing, childish – but for it to have happened to these women too was inexplicable.

I started to read about it. Slowly at first. Some of the descriptions of coercive control I read early on felt so close to home I had to stop reading. How had I not known about it before? Would I have been able to get out of the relationship earlier if I had? Could I have warned my friends?

The term coercive control was coined by sociologist Professor Evan Stark in his 2006 book Coercive Control: How Men Entrap Women in Everyday Life. But it wasn’t for another eight years that Coercive Controlling Behaviour (CCB) became a registered offence in the UK under the Serious Crime Act of 2015, thanks to the extraordinary efforts of women’s rights organisations across the country.

Women’s Aid defines coercive control as an act or a pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim.

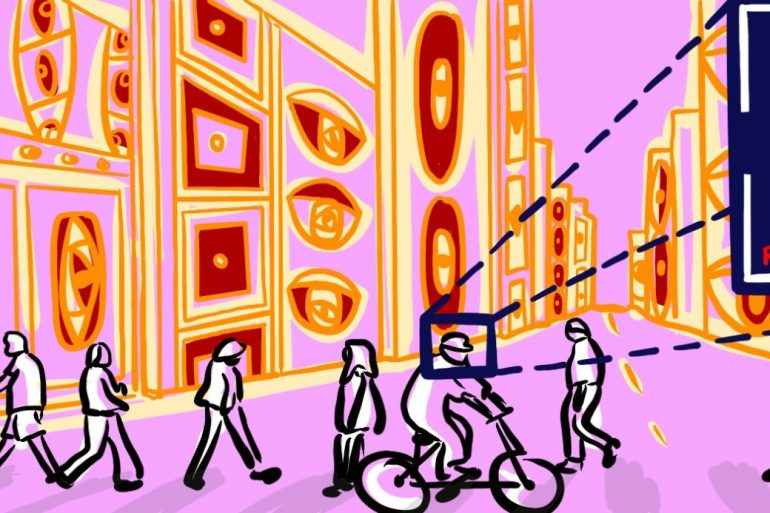

The very purpose of coercive control is to confuse the victim, to keep them on continually moving ground, to surround them with fog. Stark writes that “the victim becomes captive in an unreal world created by the abuser, entrapped in a world of confusion, contradiction and fear.”

There were 33,954 offences of coercive control recorded by police in England and Wales in the year ending March 2021, compared with 24,856 cases recorded in 2020. Almost ten thousand more reported cases, and at a time when many women were forced into lockdown with their abusers.

I couldn’t help wondering if this rise in offences was because coercive control was a relatively new crime (the most recent Domestic Abuse ONS report suggests the rise ‘may be attributed to improvements made by the police in recognising incidents of coercive control and using the new law accordingly’), or was it because the name was beginning to enable women to identify a form of abuse that had been operating for centuries? For millennia?

Statistics show that women make up 95% of those who experience coercive control and 74% of perpetrators are men (according to a 2018 study by Merseyside Police) – but coercive control, by its very nature, can be present in any type of relationship between two or more people of any gender identity or sexual orientation.

It is an age-old story of power and possession. The following two sentences are a generalisation, but I believe that the point must be acknowledged: Most people who identify as female are socially conditioned to be polite, compliant, and wary of aggression. Most people who identify as male are socially conditioned to be dominant, strong, and wary of weakness.

These discrepancies can lead to some male partners in heterosexual relationships taking advantage of societal imbalances and using coercive and controlling behaviour to dominate female partners. The most common disguise male perpetrators use to cover controlling behaviour is, devastatingly, ‘love’. But, as criminologist Jane Monckton Smith writes in her recent book In Control: Dangerous Relationships and How They End in Murder: “Possession is about ownership of property, not about love.”

What I couldn’t fathom was how insidious and far-reaching this behaviour was; this need in many men for possession and control of women. How could one quantify the scale of coercive control throughout history, throughout the world?

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

Writing Ceres

So I started to write. I wanted to explore the psychological damage of coercive control, and what social isolation, loss of self-worth, loss of agency and independence can do to a woman. I wanted to explore why it is so hard for so many women to leave, even when they can identify the behaviour as wrong.

When I was little, Mum had told me the story of Ceres, Goddess of the Harvest, and Proserpina, her daughter. Proserpina is abducted by Diss, God of the Underworld. Ceres searches the earth to find her daughter, destroying crops and drying up rivers. Eventually, learning where her daughter is, she begs Jupiter, King of the Gods, for her return. But Jupiter allows her only to have Proserpina for half the year. For the other half, Proserpina is to be with her abductor, giving us Spring and Summer when she is on Earth, and Autumn and Winter when she resides in the Underworld.

The myth has always haunted me and, with everything I’d learned about the nature of coercive control, I found myself writing a short film about a daughter, Proserpina, coming home to her estranged mother, Ceres, to seek refuge from her emotionally abusive relationship. The film follows the two women attempting to reconnect whilst planting a garden together. But, because so many women do not have the emotional or financial means to leave their controlling partners, it was important to me that the film was not a story of escape, but of the psychological complexities involved in considering leaving.

I felt angry about the depictions of coercive control I’d seen on screen. The perpetrator was often at the centre of the narrative, and often handsome, which had the disturbing effect, whether conscious or otherwise, of making coercive control seem sexy. I knew in my story I did not want the perpetrator to appear at all, to take his voice and face away, and to simply focus on the effects of coercive control on a woman and her mother.

But as I wrote, I felt the weight of so many women’s personal experiences of coercive control. My experience of it was short-lived. I got out quickly. I didn’t have children. We weren’t married. Who was I to write about this? All I could do was keep reminding myself: There are as many stories of coercive control as there are survivors of it. This is your experience and you are allowed to tell it. You lost your voice then, but you can use it now.

Filming Ceres

Before we knew it, we were shooting the film with a 90% female identifying crew, all humblingly talented, in rural North Norfolk. I remember a particular moment I had standing on set, when my breath caught in my chest and I felt the weight of what we were doing.

This felt to me then like a domino effect of actions and consequences stretching back through time and history: a painful, humiliating stretch of my life; Mum’s voice as we walked through Norfolk amid the incessant buzz of text messages; her past relationships that she revealed to me, those of her friends, of mine; a collective of people with whom the story has resonated, who have supported us financially and emotionally, who share the drive for furthering the conversation on coercive control; the campaigners on whose shoulders we stand who worked for decades to make coercive control a crime and gave women the language to identify the abuse; Ovid, who two thousand years ago wrote a story about the pain caused by forced male possession of a woman’s body.

There is so much still to be done in the education of individuals and organisations across the world regarding freedom in intimate relationships. But in that moment, standing on set, thanks to the support of women and an ancient story, I felt that my own wound of coercive control was healing, and that the light in my lighthouse was back on.

What can you do?

Organisations that offer support:

Read:

- In Control: Dangerous Relationships and How They End in Murder by Jane Monckton Smith

- Coercive Control: How Men Entrap Women in Personal Life by Evan Stark

- CCChat Magazine, edited by Min Grob

Listen:

- Woman’s Hour – Coercive Control

- En(gender)ed Podcast

Ceres is directed by Amelia Sears and produced by Cat White at Kusini Productions. It stars Juliet Stevenson and Hannah Morrish. Ceres is supported by Beth Chatto Gardens and Eastgate Larder. The film is in support of Women’s Aid. Release: November 2022

If you have been affected by this article, or know anyone who might need help, you can find more information here.