Who are you?

What makes you, you?

Is it the shape of your face? Perhaps the distance between your eyes? Are you the way you walk? Or maybe the way you sit on a chair? While all of these things do form part of your identity in isolation, what can they really tell someone about you?

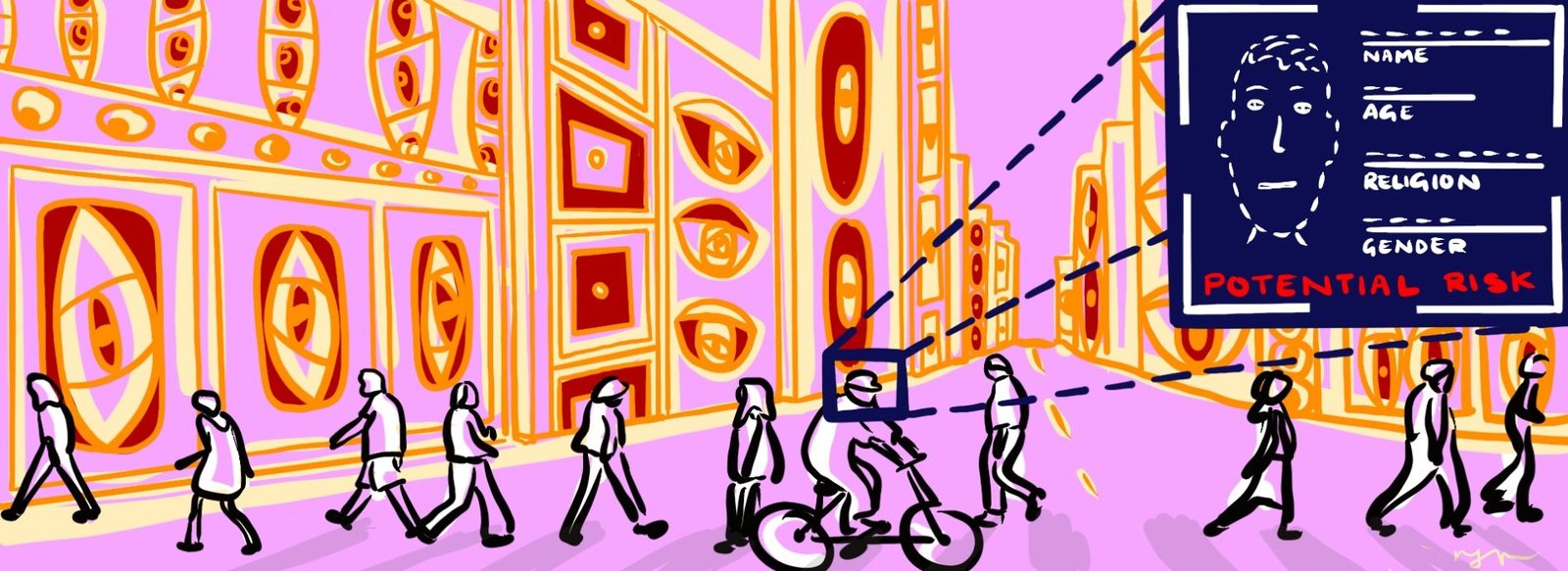

Certain data about your body and behaviours are unique to you and you only. These are called your biometric data. The use of your biometric data can reduce the complexity of your entire identity to a data set. In the wrong hands, this data can be used to target you, stereotype you and even make ‘predictions’ about your behaviour.

After being captured by technologies like facial recognition, governments and companies use your biometric data to make judgements about your feelings, your intentions, your gender, your sexual orientation and even how ‘dangerous’ you are. Such technologies are currently spreading in publicly-accessible spaces: our train stations, stadiums, supermarkets, streets and public squares.

The monitoring, tracking and otherwise processing of biometric data of individuals or groups in an indiscriminate or arbitrarily targeted manner in our publicly-accessible spaces gives rise to a new form of mass surveillance: biometric mass surveillance. And while this precedes COVID-19, the pandemic has given state and private actors a new narrative by which to expand unlawful, highly-intrusive bodily and health and mass surveillance systems under the guise of public health. Whilst taking proportionate public health measures is a legitimate policy action, there is a significant risk that the damage caused by widening surveillance measures will continue on after the threat of the pandemic has passed.

History class: Using the body against the human

Historically, people’s bodies have been used against them at both an individual and community level. Your skin, face, gender, disability status – these can, and all have been, used to categorise, discriminate against and harm people throughout history.

Painful examples come from systems of brutal oppression established through discrimination against racialised people in the US, South Africa and other settler colonial societies. Examples also spring from the Nazi regime using the size of someone’s nose or head to decide if they would be a target of the Holocaust. Historically, people with disabilities have been the subject of societal fears, intolerance, ambivalence, prejudice, and ignorance. Women and gender non-conforming people have been stereotyped and refused access to services which reflect their choices.

And then there’s phrenology, the nineteenth-century fake science of judging character and potential of a human based on the shape of the skull. It is also physiognomy – a pseudoscience which revolves around the practice of using people’s outer appearance to infer their inner character. Many have argued that, when put into practice, physiognomy becomes the pseudoscience of ‘scientific racism’.

Today’s biometric mass surveillance tech is patriarchal, ableist and racist

Fast forward to the 21st century. Humans have developed technology that surveys and categorises our bodies, using techniques and assumptions that are grounded in phrenology, physiognomy and scientific racism. These are then deployed in ways which perpetuate discriminatory attitudes against women and LGBTQI+ communities, racialised communities, people with disabilities and neurodiverse people.

Governments and technology companies are deliberately ignoring the lessons of the past. In an innovative way of washing their hands of any responsibility for the systemic harms caused, powerful actors claim new emerging technologies such as those used for biometric mass surveillance are unbiased, objective and reliable. In actuality, biometric mass surveillance technologies often exacerbate and amplify patriarchal, ableist and racist power structures and discourage people from freely mobilising against injustice.

So-called ‘researchers’ base their studies on phrenological principles, even claiming one’s face can reveal sexual orientation. The potential danger this poses for queer people is immense. Imagine what authoritarian regimes could use these technologies for, regimes known to oppress individuals based on their sexual preferences. With rising xenophobia across some EU states (see Hungary’s recent “anti-LGBTQ” law), these technologies can be used to further persecute and exacerbate hate against LGBTQI+ people.

Moreover, people’s faces, voices, bodies, and even the size of their feet have been used by the biometrics industry to try to predict a person’s gender. This can harm the dignity of trans people by mis-gendering them based on a discriminatory machine’s predictions. It is a really intrusive use of technology, and it can deny trans people the autonomy and the freedom to express themselves according to their gender identity. It also harms anyone that does not conform to an arbitrary and archaic binary standard of gender, violating everyone’s ability to express themselves and identify as they choose. Companies use facial recognition to advertise to us based on who they think we are: guys get a pizza ad while women get the salad ad.

In a reality in which we are all aware of unjust police profiling practices targeting immigrants, racialised communities and ethnic minorities, technologies are often portrayed as an ‘objective’ way to counter potential officers’ ‘subjectivity’. However, anti-racism groups have been blowing the whistle on the discriminatory over-policing of racialised communities linked to the increasing use of new technologies. In particular, facial recognition has been proven to judge Black faces to be angrier and more threatening than white faces, and this has been adopted by a worrying number of police departments across Europe and beyond. Several people of colour have already been wrongfully arrested due to this.

Human rights defenders have been intimidated and silenced from speaking truth to power. In Russia, people are picked up from the street for questioning, after being singled out by cameras in Moscow for taking part in political rallies. In the US, racist facial recognition technology is used against people protesting the exact systemic racism this technology exacerbates. Not only does such technology risk mis-identifying people, but it creates chilling effects among those willing to use their democratic, civil rights to organise and ask for social change. It risks creating societies of suspicion, in which every single one of us is treated as a potential crime suspect.

But we can still fight it.

We’re taking back our bodies, we’re reclaiming our faces.

The only good thing about biometric mass surveillance? We can still do something about it. We are humans: so much more than walking barcodes, so much more than our data. We’re organising with strategy, vision and community power.

In the recent past, people across the globe have been coordinating actions against biometric mass surveillance. Resistance has mounted against facial recognition mass surveillance technologies used by UK police forces; against Spotify’s mass speech recognition; against São Paulo’s metro gender and emotion recognition and China’s surveillance of Uyghur minorities’ bodies.

In 2020, people in Europe started to organise across borders. The #ReclaimYourFace coalition, now counting over 60 civil society organisations, demands a ban on biometric mass surveillance across all countries in Europe.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

In 2021, the campaign launched a European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI) – a unique petition that citizens in the EU can sign to demand new laws, in a process similar to electoral voting. So far, more than 50,000 people have supported this initiative.

Beyond the support for the ECI, #ReclaimYourFace has had an immense impact. Almost 300 Members of European Parliament supported our call for a ban on biometric mass surveillance. Data Protection Authorities in Germany, Italy and Netherlands also spoke against these technologies. Most recently, the two most important regulators for ensuring people’s rights to privacy and data protection across the EU announced their formal support for our call to ban biometric mass surveillance practices.

But we need to do much more in order to have a real and lasting impact.

As the EU is making new laws on Artificial Intelligence, there is a risk that a new law could legalise biometric mass surveillance.

On one hand, the Commission acknowledges that biometric mass surveillance practices have a seriously intrusive impact on people’s rights and freedoms, as well as the fact that the use of these technologies may “affect the private life of a large part of the population and evoke a feeling of constant surveillance (…)”

However, on the other hand, the law proposal contradicts itself by permitting certain forms of biometric mass surveillance that it has already acknowledged are incompatible with our fundamental rights and freedoms in the EU.

Specifically, one must look at the proposed prohibition of “real-time remote biometric identification” for law enforcement purposes. Beyond vague wording that leaves a lot of room for interpretation, some of the biggest issues in the proposal’s approach are that the prohibition fails to address equally invasive and dangerous uses by other government authorities as well as by private companies. Moreover, the prohibition on law enforcement uses has many exceptions which are defined too broadly and could leave room for continued biometric mass surveillance of the public space by law enforcement authorities. Finally, only “real-time” identification for law enforcement purposes is prohibited. This means it could be possible to identify people after the data has been collected (“post” / after the event) – making notorious Clearview AI databases completely ok to be used by the police.

Negotiations for this law are expected to last at least another year. A tough journey lies ahead and we need everyone to succeed in banning biometric mass surveillance across the EU. Join the fight today, while change is still possible, and you will have a real impact on the future of our societies.