Peckham’s Rye Lane in late July, and there’s rhythm in the air. Soundtracked by the sizzle snare of a suya grill and sounds of the diaspora from a nearby boombox, I’m on my way to Nola Coffee to meet a Sunday Times-bestselling author who imbues his writing with similar timbres and tones – a style that, as he puts it, helps “bridge the gap between emotion and expression.”

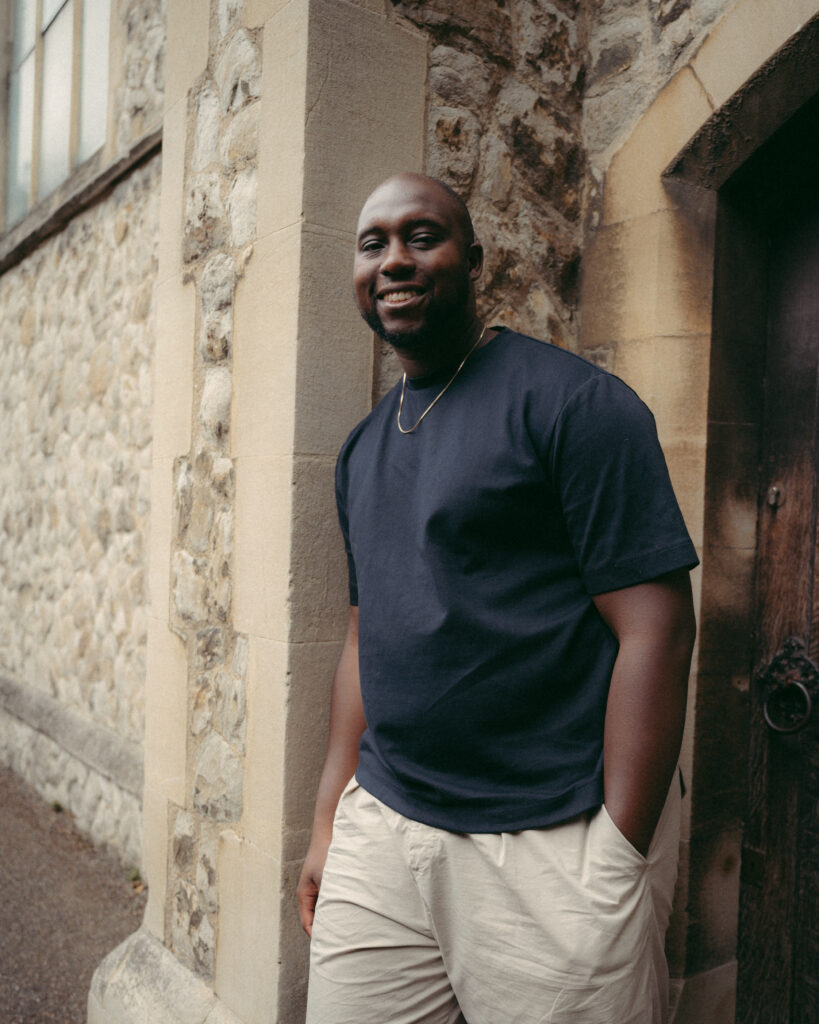

Caleb Azumah Nelson is a rare breed. The kind of multi-hyphenate artist whose disciplines complement and improve each other with every string he adds to his bow. At only 29 years old, he’s found his freedom in music, photography, film and prose, developing into a storyteller whose reputation for poeticism and tenderness precedes him.

Caleb’s debut novel, 2021’s Open Water, earned him national recognition, culminating in the Costa Book Award for First novel that year. His writing has been described as simultaneously intimate and expansive, handling nostalgia with nuance, whilst creating new settings full of life and energy. In this sense, Small Worlds, Caleb’s latest release, is joyously more of the same.

The novel follows the story of Stephen – a young man on the verge of adulthood, leaving school and discovering himself along the way; through music and dance, through his family dynamics, and through his relationship with childhood friend Del. Set against the backdrop of South East London in the early 2010s, it’s quickly apparent this is a setting the author knows well.

And as I take my seat opposite Caleb to discuss Small Worlds, we dive straight into a discussion on how this second novel marks a shift in his artistic journey.

“I think that the novel presents to me this very broad space, in which I can just kind of roam about, just by myself” he begins, “and it’s where I can hear my voice the clearest.”

This clarity of expression is what helps Caleb write not only with personality, but with speed. Both Open Water and Small Worlds were finished in a matter of months, a writing method Caleb describes more like a “trust exercise” than your typical process. “The work lives in my mind for so long that by the time I get to the page, the voice is the main thing I’m looking for,” he explains.

In Stephen’s voice, Caleb finds exactly what he’s looking for to tell a story that uplifts, devastates and rebuilds its reader. Drawing on influences as diverse as Zadie Smith, Barry Jenkins and, crucially, Kendrick Lamar, Small Worlds reads like a song.

There’s lyricism on Caleb’s page, underlined not only in his use of repeated linguistic motifs and phrases that recall verse, bridge and chorus, but also in their subtle changes of tone – hints that guide you through the emotional beats of Stephen’s life like note shifts that progress a symphony.

“You’re only as good as your last sentence,” says Caleb of his process. “And despite the language I’m using often being described as poetic, I’m trying to be as simple as possible and think about the ways in which I can give as much power to my sentences as possible with that simplicity.”

He continues: “I’m always thinking about the way in which things operate on a sentence level.” But despite this meticulous attention to detail, Caleb maintains that he’s never really thought of himself as a perfectionist – although he can see the irony in his self assessment. “I told my partner the other day and she was like, ‘What are you talking about? Like what?’ But I think, I’m very happy for things not to appear rigidly perfect.”

In building his narrative this way, Caleb gives Small Worlds a sort of meandering quality in its early chapters. Reminiscent of the summers of youth, we’re with Stephen as he settles into an easy freedom during long summer days. Sentences become paragraphs, paragraphs then pages, pages into chapters. Before long, the first section of Caleb’s three-part tale comes to an end – and as Stephen learns more of himself and those he holds close, the tone of the novel shifts again.

Memories play a huge part in Small Worlds’ character dynamics. For Stephen, his brother Ray, his Mum and Pops, and Del, generations of experiences, behaviour and beliefs reveal themselves in ways that don’t always seem to make sense – and it’s here that Caleb makes a powerful point about how much we can ever truly know those we love.

He likens his use of memories in the novel to the “ways in which mirrors don’t ever show a true reflection.” And in this comparison, he reveals the layers to his characters. “Each time you remember something, you’re warping that memory. But each time you remember, you become surer of it. And it’s just such an interesting thing to me that you could become sure of something that’s falling apart.”

Caleb was intrigued, he says, by “that concept of the ways in which our realities are mirrored within each other. Especially those relationships that are close and intimate, how they show us different parts of ourselves. So I think that was a big consideration throughout.”

But there’s arguably no relationship more close and intimate than that of an author and his central protagonist – and when I come to question Caleb about his ties to Stephen on a personal level, he’s quick to explain.

“Stephen and I diverge a lot. And I think there’s something that he has – this real melancholy – to him, that I have a glimpse of,” he says. Stephen’s melancholy is more an exaggerated depiction of his own; an unreliable mirror. Caleb found a more fitting point of reference for Stephen’s character in John Coltrane, whose “painful smile” provided the ideal jumping off point when it came to building the narrative of his leading man.

Coltrane’s story of struggle and redemption reflects Stephen’s almost directly. But there’s a common thread that ties all three subjects of our story, Caleb included, together. Freedom.

Having space to freely express oneself is something Caleb holds dear. From experiencing “these small and loose gatherings, these acts of resistance” against community erasure in London following the 2011 riots, to finding his voice in his art, Caleb has long searched for ways to give truth and power to the stories around him.

“I think the striving for a sense of space is something that Stephen and I share,” he says. And as our conversation continues, I see how clearly this comparison shines through.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

Caleb returned to Ghana last year to visit family, a near-identical trip to one Stephen makes in the novel. “That was a really beautiful thing for me. The food, the heat, the way that light moves there – it’s just a very specific thing.”

He tells me that after he got back to the UK, “I felt more like myself for sure. Or like I’d begun to access parts of myself that I hadn’t necessarily been able to. One of my friends last time she saw me was like ‘you seem bigger’ and I was like, yeah, kind of growing into my own body.”

It’s interesting to note what these trips, both on the page and in reality, result in. There’s an assuredness and a peace to Caleb that radiates effortlessly. He found comfort with himself, and in that comfort he found the power to complete his journey, adding an element to Small Worlds that takes the story from compelling to heart-wrenchingly irresistible.

Representations of masculinity and male familial ties run throughout the novel, and without dropping any spoilers, we’re left with a tender yet hopeful picture of a man in ruin. This is where Small Worlds hits hardest, but it’s a place Caleb didn’t realise he’d reach.

“The novel I wrote is not the novel I pitched to my publishers. They always laugh about that,” he admits. He’s happy to recount this detail, and so he should be. In Small Worlds, he’s crafted a tale that captures so many target areas and will mean so much to so many. It’s a guiding light for young people, an exploration of love and life, and a touching representation of what it means to be a man, in a setting we might not expect to see such a story. Overall, there’s a feeling of hope as you reach the final meticulously crafted – although not perfectly planned – sentence.

“My favourite stories don’t have an end point. What I’m always striving for is possibilities,” he says as our conversation reaches its end. “I really wanted this novel to feel like there was hope on the other side of it.”

It’s a goal he’s certainly achieved. And on the other side of Small Worlds for the man who wrote it? “The novel’s actually part of a loose trilogy,” he says. “So there’s one more that I want to write and then… go to the mountains for a bit. Retirement.”

If there’s one thing we need more of, it’s more stories from the hand of Caleb Azumah Nelson. I sincerely hope, for fans of his work past, present and future, that he doesn’t take that trip.

What can you do ?

- Read Open Water and Small Worlds to get acquainted with Caleb’s work.

- Listen to the Official Small Worlds Playlist – a collection put together by Caleb himself, made up of the soul, grime, garage and afrobeat music soundtracking Stephen’s story.

- Watch documentaries around the 2011 London Riots like The Riots 2011: One Week in August and The Hard Stop – for a deeper understanding of the backdrop to Stephen’s character development.

- Listen to Sounds of Black Britain – a 2022 podcast that used music as an educational resource to understand the Black British experience.

- Keep your eyes peeled for Caleb’s directorial debut Pray, a reflection of brotherhood and seeking light in times of grief, dropping soon.

- Read: Caleb Azumah Nelson on Open Water – Shado Magazine