When you first dip your toes into the waters of the climate justice movement, you’re immediately struck by how complex the problem is. It’s not just global warming, fossil fuels and melting ice caps, as a science-based approach would have you believe. It touches everything from fair and equitable pay to sustainable housing, inclusive urban spaces to land rights, communication methods to culture change. In other words, it is a systematic problem that we all both contribute to and benefit from in some capacity. And you very quickly realise that you can’t single-handedly resolve it all.

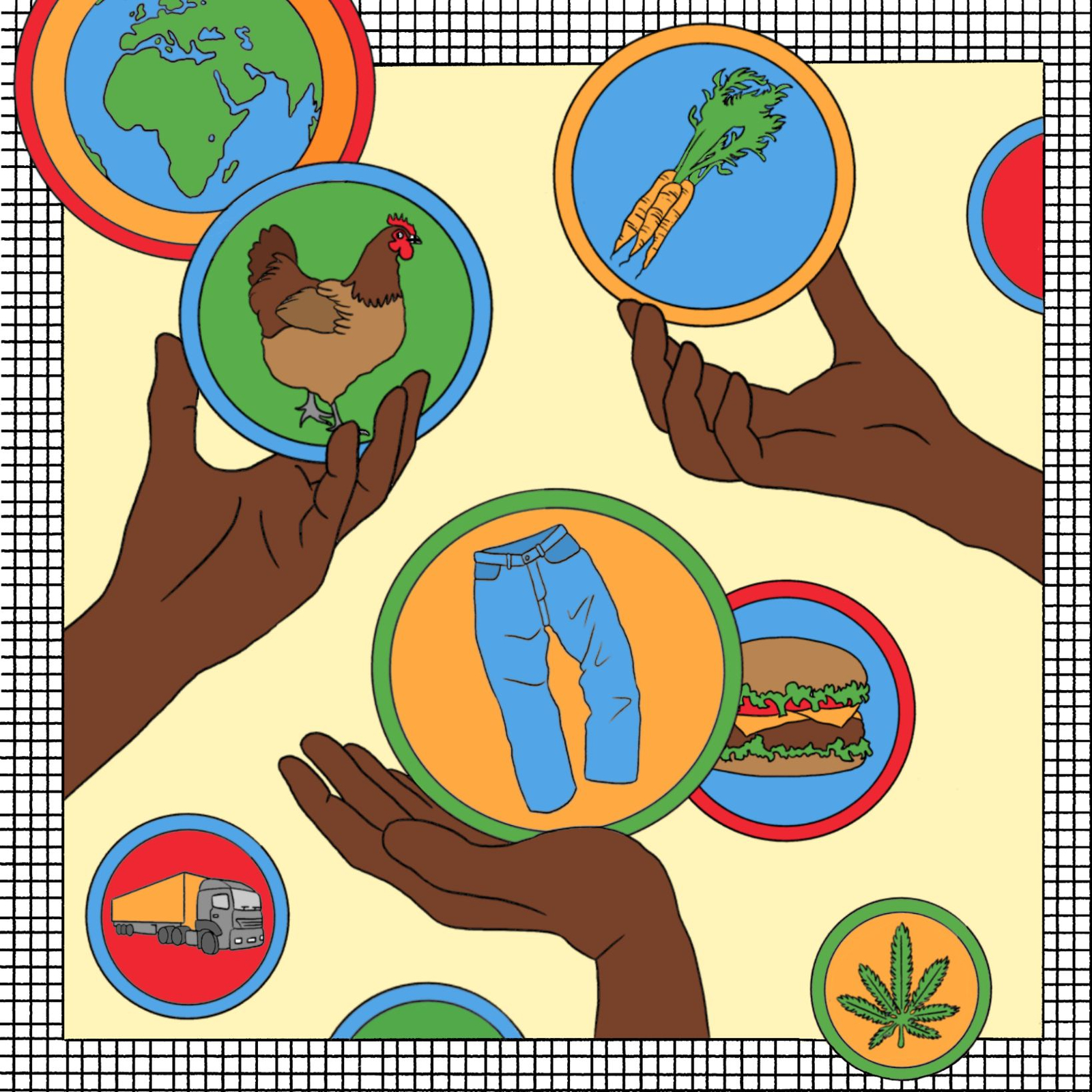

The depth and magnitude of the problem can be daunting, so much so that people switch off and stop trying altogether. For Whitney McGuire, the co-founder of Sustainable Brooklyn alongside Dominique Drakeford, the only way around this potential inertia was to start small. They took a community-centric approach, opening up a localised discussion, before letting that impact branch out in due course. “Our first event was a town hall, and we had an incredible turnout,” Whitney remembers. “We had a panel lined up, but the event turned into a lively discussion where everybody in the audience spoke up and to each other.” From this first event came Sustainable Brooklyn’s focus areas, deeply political issues for the Black community, that act as the organisation’s pillars and research areas: fashion, food, and wellness.

The three are interlinked, all with deep-rooted histories in environmental injustice and coloniality, but for Whitney, her journey began as a paralegal. While studying and practising law itself wasn’t for her, she found a middle ground that suited her in the field of fashion law. “I was so blown away by the subject matter and how comfortable I felt with it,” she explains. After going to Fordham University’s Fashion Law Symposium, and thinking about building a fashion law curriculum at her own university, Whitney chaired Fashion Law Week, a week-long conference that explored issues at the edge of fashion and law. She was involved in drafting legislation that introduced copyright protection for fashion designers, and today, has expanded her practice to cover legal issues across the creative, arts and culture industries. “We see a lot of exploitative practices when it comes to licensing, as well as labour exploitation for emerging artists,” she explains. And despite the growing awareness of exploitation in the global fashion business, she believes it is still going largely unchecked. “Even though sustainability is becoming popular, the concepts are not translating into contracts. We’re still seeing run-of-the-mill exploitation of artists, designers and makers.”

Through her learnings in the fashion industry, Whitney came across the disturbing history of denim: “Denim has its origins in forced labour and slavery. The first iterations of denim were called ‘slave cloth’ because the material protected slaves from the prickliness of the cotton.” Since then, overalls had become a symbol of civil rights movements, and denim and hip-hop became synonymous. Learning about the roots of denim, and its role across fashion, labour and agriculture, gave rise to Sustainable Brooklyn’s second priority: food. “Agriculture is rooted in our origins and Black farming is how we got here, but today, over 50% of Brooklyn is food impoverished,” Whitney highlights. And it’s not because of food deserts, she says. “A desert implies a natural process of weathering. This is food apartheid – it is strategic and directed.”

Cannabis farming is a near perfect example of the exploitation of Black communities and labour, and the way that agriculture and wellbeing are connected. On one hand, historic policing and legislation of cannabis, especially in the USA, has unfairly targeted Black communities. More recently, however, the rise of the CBD wellness industry has seen countless white entrepreneurs profiting from the same plant that Black people were being arrested for. “Wellness is still a privilege afforded to a certain type of person,” Whitney says. “Black farmers have never had the same treatment as white farmers.” It’s this systematically and infrastructurally unfair treatment that means that Black, Indigenous and PoC farmers – and wider communities – find themselves working twice or three times as hard for the same end result as white farmers and communities. For Sustainable Brooklyn, it is one thing to recognise this imbalance in work and wellness. The next step is to embed practises of radical rest and education about structural inequalities affecting Black communities’ wellbeing, which quickly became the organisation’s final strategic focus area. “We all just want to heal from this legacy of being exploited for our bodies, labour and minds,” Whitney highlighted.

Armed with their three priorities, Sustainable Brooklyn started hosting their WTF event series. These served to unravel the current state of fashion, agriculture and wellness, all in the context of environmental sustainability and race, in collaboration with the likes of sustainable fashion writer Aja Barber, bamboo toothbrush entrepreneur Manju Kumar, and BIPOC membership network Ethel’s Club. These needs-focused events, combined with Whitney’s legal background, have recently got her thinking about the concepts of negligence. “There is no standard duty-of-care for Black lives,” she explains, “and the harm that results from that lack of core damages [are owed] to that person to make them whole again. So whose responsibility is that?”

Sustainable Brooklyn recently began pioneering the idea of consumer-led standards of care, again emulating their needs-based approach to community outreach. Companies can pledge to uphold these standards of care, and are added to an online directory. “We plan to support small businesses who seem to not be able to uphold these duties of care, especially if they are black-owned. We’re also looking to enlist data strategists to the team.” Whitney also doesn’t shy away from recognising that we all exist in the system of capitalism, and that we can’t always simply point fingers at businesses who are trying. “Capitalism in this new age of awakening means that everybody ends up cherry-picking the type of sustainability they want to be involved in, and they end up greenwashing. At this point, who isn’t doing that? These businesses also need to sell products, at the end of the day. Doing something in the first place should be enough.”

See more of Marcie’s work on her instagram HERE