I was 11 when my uncle Bhirty died. I have no real memory of him. He moved to France in 1986, part of the diaspora seeking a better life elsewhere. He became an artist, a painter. He never returned to Mauritius, until his body arrived in a lead coffin in 1992. I didn’t grasp how tragic it was to die at 32.

My mum, the eldest of nine, was a mother figure full of grief, distressed at not being by her brother’s side while he died slowly in a hospital in Paris. She couldn’t hear his voice as often as she would have liked during his final days; overseas call rates were exorbitant.

My grand-mère, a widow since 1978, was inconsolable, heartbroken at seeing one of her youngest children disappear into the ground.

I didn’t ask questions. I found out later on, through snippets caught here and there, that he was gay and died of AIDS-related illnesses.

I do remember that he wrote regularly to my mum. He sent cards and photographs of places he’d visited. I have vague recollections of an invitation for an art exhibition in a Paris-based gallery. I thought he must be talented and well-known.

Bhirty gave mum two paintings that became part of the memorabilia we grew accustomed to at home. One of them now hangs in my Sydney apartment.

I didn’t think of him often over the years. But in 2018, as I finished writing my book on arts-based research, my thoughts wandered back to artists in my family and to Bhirty. It occurred to me that I didn’t know much about him, let alone his art. The whispers surrounding his death meant that I had no knowledge of his legacy.

I Googled him. I found a webpage with details of his life and passing, his inspiration as a self-taught artist, and pictures of his art*.

I felt ashamed. I knew none of this. Who had created this loving tribute to my uncle?

The website was for a quaint guesthouse with an art workshop in rural, southern France. Bhirty’s unmistakable style adorned the walls of the guestrooms depicted in photographs.

With a mix of excitement and anger, I sent the link to my mum, hoping that she knew who was curating her brother’s art and sharing it online.

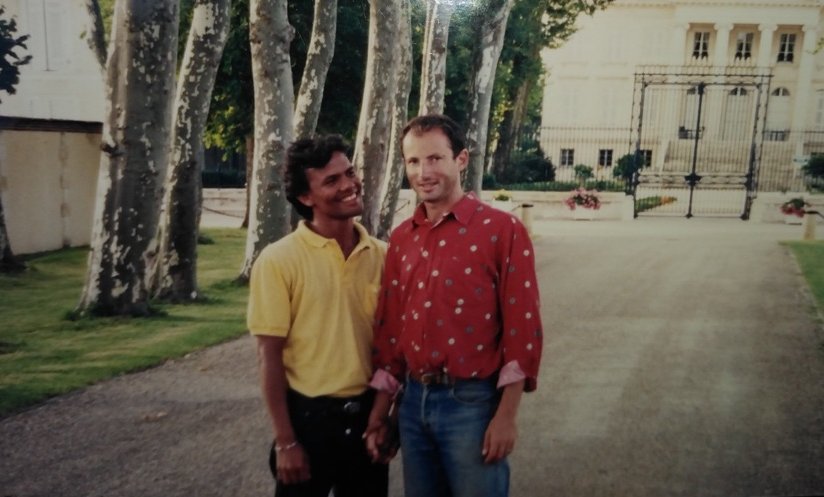

She found out that the guesthouse owner was Bhirty’s former partner, Stéphane, himself a talented artist. Mum, who’d thought that Stéphane had died many years ago, reconnected with him via email. Less than a year later, she travelled to his guesthouse. They spent time talking about the painful and beautiful story that linked them forever, surrounded by Bhirty’s art. Their unexpected encounter was one of life’s best surprises.

Mum brought back old photographs, Bhirty’s drawings that Stéphane gifted her, and books with Stéphane’s poems about the man he loved. She wrote down what she learnt from her conversations with Stéphane, and her favourite memories of Bhirty.

I found out that he was an undocumented migrant, a sans-pâpier. In my work, I’ve heard countless stories of people living precariously with the fear of deportation, and getting by under the radar. I had no idea that a member of my own family had experienced this uncertainty.

I’ve gleaned more details about 1992. Grand-mère had not wanted Bhirty’s body repatriated to Mauritius, even though it was his wish to be buried with his father. Perhaps the shame of having a gay son amid a conservative clique – even though it’s unclear who knew about his identity – was stronger than her desire to have him back in his home country. She is now too weak and angry at the god who took three more of her children to remember why.

Stéphane wasn’t able to travel to Mauritius for the funeral. He was completely broke after spending his life savings on Bhirty’s palliative care. Shortly before he died, Stéphane had organised an exhibition to sell Bhirty’s art to help cover the costs. They stared death in the face together.

I struggled to understand the pain of being excluded from this final ritual and never being able to visit his grave thousands of kilometres away.

Borders and distance determine the shape of grief.

In France, Bhirty lived freely in a same-sex relationship, and travelled to many cities with his art. He couldn’t have lived authentically in his homeland. Perhaps the metaphors he expressed through his art conveyed the strain of hiding his true identity from loved ones.

In Mauritius, his life-death remained taboo for many years, so memories are a bit blurry.

I wrote to Stéphane in December 2019. He could sense I was searching for answers – or forgiveness on behalf of my family? He was pleased that his efforts to preserve Bhirty’s legacy had led us to him, after so many years.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

He was generous with stories to fill in the blanks. Their initial concerns over Bhirty’s rapid weight loss, their reticence to use the healthcare system because of his status as sans-pâpier, Bhirty’s anguish when he knew he was going to die, and how he thought about nothing else but painting.

Stéphane supported Bhirty’s artistic endeavours, his only source of solace. His skills improved, his mysterious and intimate style became more distinctive. There was an urgency to express his creativity at every opportunity.

Now 60, Stéphane still finds it hard to accept life’s unpredictability and injustice.

But he told me, with all his French directness:

‘Don’t judge those who weren’t there for Bhirty.

It was a different time, and people do what they can.’

I was touched by his insight and his lack of bitterness.

His words gave me permission to appreciate this story for what it is.

Bhirty would have been happy that his eldest sister met the love of his life in person. That his art – his legacy – is borderless. That he rests in his birth country, finally at peace.

See more of Cindy’s illustrations on her instagram @cindysykang

This piece was originally published by Routed Magazine. The piece has been adapted with new imagery for shado’s Build Love, Break Walls long-form journalism project, which has been spotlighting the experiences of those from within the LGBTQI+ community who are refugees, or claiming asylum.