When the British Council invited me to attend the opening of the British Pavilion at the 18th Venice Biennale of Architecture, I was both excited and a little dubious. The Biennale is an international exhibition of architecture held every other year in Venice.

Known as the ‘olympics of architecture’, the best and brightest architects from across the world respond to a collective theme and are showcased in country pavilions and free side events throughout the city. This year, Lesley Lokko, a Scottish-Ghanaian architect, was named lead curator – the first person of African heritage ever to do so. The theme, The Laboratory of the Future, requested global contributors to focus on decolonisation and decarbonisation and asked ‘What does it mean to be an agent of change?’

‘Central to all the projects is the primacy and potency of one tool: the imagination’ explains Lesley to Design Boom. ‘It is impossible to build a better world if one cannot first imagine it.’

Across all sectors, all of us are in desperate need to meaningfully engage with imagining how society can work outside of anything we’ve ever known. With the built environment contributing over 39% of global energy related carbon emissions and the continued physical and social exclusion to marginalised identities across the globe, the architectural biennale engaging in radical futures feels overdue.

Yet these events – international fairs to which critics and practitioners fly in from across the globe – are riddled with elitism: how far can an event like this actually contribute to radical change? Entry to the Biennale costs €25.50, so immediately it’s not for everyone. Before arriving, I had read how the Austrian pavilion had planned to make their contribution free for the local community and reverse the spatial practice of exclusion – which was then denied by city officials.

Further, Lesley had released a statement on how many of her core team had been denied visas by the Italian government, accusing her of trying to bring ‘non-essential men’ into Europe. And more broadly, it is the elite art world that contributes most of the creative sectors carbon emissions – the asymmetry of privilege and wealth across the sector having a concrete and large contribution to the physical consequences of climate change with the transportation of these large installations to Venice, and punters flying in from across the globe.

The very weekend of its opening, Northern Italy was hit by devastating floods leading to 13 deaths. Is the Biennale where we should be looking to dream up a fairer future, when so many issues of exclusion and social injustice are tied into its operation? Could this be just another performance for rich audiences?

These were the questions weighing on my mind as I entered the British Pavilion, which was Britain’s contribution to The Laboratory of the Future. The curatorial team, Jayden Ali, Joseph Henry, Meneesha Kellay and Sumitra Upham – all British born socially engaged architects with diverse practices, experience, and heritage – dreamed up the exhibition entitled Dancing Before the Moon. Inspired by a James Baldwin quote, the curators asked six artists to consider the rituals of Britain’s diaspora communities, the social practices across geographies and histories that hold us together.

“There is a reason, after all, that some people wish to colonize the moon, and others dance before it as an ancient friend.” (James Baldwin)

Collectively, they were asking: how might we rethink space to celebrate these acts of community, rather than be relegated to the spaces in-between? How do we actually navigate the built environment to come together, and how could British architecture transform to nurture this?

As Joseph and Meneesha guided us around the exhibition, my apprehensions began to dissipate. We were first greeted by the sound of steel pans, echoing off cold white walls lit up by the flickering colour of a huge curved screen. A film, produced by Joseph and Meneesha, spliced together flickering images of working hands: hands braiding hair in a salon, frying okra at a market, gardening in an allotment. Colourful, ritualistic, highly skilled work. We lay down on the sloped floor to take it all in. The hands work so deftly you’d think it was easy, but have been honing their craft for years. Crafts which bring us together, provide us food, happiness, health – rituals of diaspora communities appreciating the land and each other.

We were then moved through to the first of the offshooting rooms, each of which house an installation responding to a chosen ritual of a commissioned artist. Shawanda Corbett’s A Healing is Coming which displays a series of metallic vessels, pulling from the voodoo and hoodoo culture of her upbringing in Mississippi. Shawanda was born with one arm so uses her body to craft the pieces, which represent an imagined group of women embarking on different journeys towards healing.

“The fact she has mastered this piece of technology (the pottery wheel), which was never designed for her, is very powerful – she’s re-owning it,” explains Joseph.

We move to the next room, where Nottingham’s young furniture designer Mac Collins filled the space with what he describes as an ‘imagined artefact of the future and past’. The enormous floating ash construction is an ode to the practice of playing dominoes with his family and community, essential to his personal cultural connection to his Jamaican heritage. For Mac, the piece carves out space for the rituals of play of West Indian communities. Henry emphasises this significance: “No one who designed spaces [in Britain] considered there was a West Indian community there. We don’t see West Indian older communities in public space because the infrastructure and the objects aren’t there.” Kellay agrees, adding that “when they play dominoes, they are making space.”

Only in May 2022 did Westminster Council serve an injunction against a group of friends (all older men of West Indian heritage) who used Maida Hill Square to play dominos, cards and backgammon. Westminster Council’s claims of ‘anti-social behaviour’ and ‘intolerable levels of noise for those living nearby’ as reason for the eviction, raised the question, who gets to police space? Who is public space for in Britain? To whom were these conditions intolerable, and why was that considered of more importance?

As we edged around the installation, the enormous, abstracted domino winked down at us, taking up the physical space its brothers are not afforded in the UK. Who gets to play in the public space in Britain, really? After decades of austerity, with community centres decimated, many have been forced into their homes or into venues where you must spend money to play and socialise together – halting community from organically forming in public. “It silos people back into the home, rather than out into public space.” says Kellay. This installation is resistance and a reminder: public space is for all of us.

The next room gave way to Sandra Paulson’s installation; a bright, bubbling blue construction which pays homage to the ritual of cleansing. Her Angolan grandmother was a Lavadeira, a person who washed clothes in Luanda, and through the piece she maps the objects of this everyday but so often invisible labour. The practice of cleaning is so vital to the economy and an essential employer. In a post-Covid world, you’d think the importance of this would have been put into sharp focus, yet it remains invisibilised.

Snaking through the exhibition space, the next room is contorted from a white cube to the cocoon of a spider or shady undergrowth of a forest. Yussef Agbo-Ola’s Muluka: 6 Bone Temple asks us to consider the more-than-human, a space to worship our environment and contemplate our rituals as tied to our ecology. Drawing from his Nigerian, American and Cherokee heritage, Yussef has constructed a temporary intricate tent like structure from digitally rendered and painstakingly physically crafted organic cotton ‘skins’ – drawing from Yoruba and Cherokee architectural histories.

The web-like structure, Meneesha informs us, is entirely transportable in a carry-on suitcase. With the travel emissions from transporting exhibitions such as these being so high, Yussef’s piece is an example of how, operationally for these events and for building practices more broadly, there are tangible, low carbon ways forward.

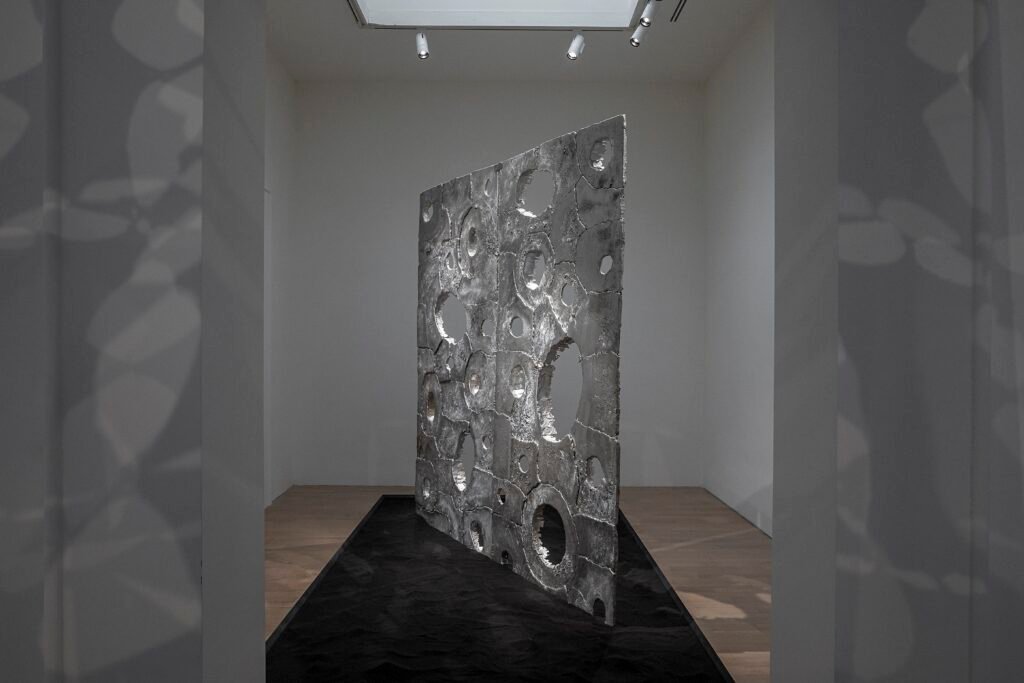

Similarly, Bardot by Madhav Kidao, just a room over, is a low-carbon aluminium wall crafted from melting down and reconstructing a previous sculpture (Between Forest and Skies) Madhav is interested in the ritual of creation through death. In the natural world, we see regeneration as an essential part of a functioning ecology, how each being that dies becomes nutrients for new growth. This impermanence that Madhav explores poses the question, what in British architecture is still serving us and our communities? What do we need, and what can be melted-down and reformed into something that nurtures us?

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

In our current political reality, the concept of ‘Britishness’ has been violently weaponised by the right to isolate, oppress and exclude. This bright curatorial team is showcasing instead that Britain is ‘plural and not isolated.’ As Joseph explains: “There isn’t a set British culture or set of traditions we have to subscribe to.”

Their contribution the Laboratory of the Future is a Britain which makes space for nurturing strong communities of love and play, acknowledging the work and needs of those currently operating in the in-between which are essential to a functioning society. “One of the most interesting parts of British culture is that of the diaspora, and we wanted to bring architecture into the conversation,” says Joseph.

“The artists we commissioned are not British born, this is a global exhibition,” adds Kellay. “Because we’re British doesn’t mean that we don’t carry things from around the world and bring those qualities to the UK in a way that enriches all of us. It’s not about like, black, brown, white, whoever it’s about us being able to appreciate one another and share space.”

What if British architecture enabled and celebrated participation, global connection, care and rich, thriving ecologies? That is a future Britain I am excited by, and that I now understand we are always making – just by using space however we need.

A quote from bell hooks adorns the wall of the pavilion: “Irrespective of our location, irrespective of class, race and gender, we were all capable of inventing, transforming, making-space.”

And she is right. I was dubious about how the Biennale, a site of immense privilege in the heart of colonial Europe, could meaningfully engage with a decolonised and decarbonised future. But the British curatorial team and their artists have transformed it. As Joseph reminds me: “When this building was constructed (in 1909), most of the countries this exhibition draws from and are connected to, were under colonial rule. In a way, the building itself represents the worst of Britain. What we’ve done is put stories into here to unpick that narrative and say, there is a different perspective.” The tangible change over that hundred years is powerful and allows you to hope that in another hundred, things will be better.

Cities such as Venice are built on thousands of years of colonialism, enslavement and crippling globally inequality. So it was significant that, in this year’s biennale, Lesley ensured over half the participants are African and of African descent.

Across the entire The Laboratory of the Future, an exploration of reclamation emerges, of holding ancestral tradition with new technologies to remake what we have now to be better. The liberated future must be built with the conditions handed us in the present, while honouring our complex past. In both the physical construction of the exhibitions, and in the occupation of the Biennale itself, the question seemed to be: how can we transform it? If we meaningfully engage with decarbonisation and decolonisation, what tensions emerge?

We can’t build a utopia if the problems remain unnamed and unacknowledged. We all want a smooth transition to a better society, but that is not how change happens. The road to a liberated world is not a frictionless one.

By bringing these questions into this olympics, Lesley has masterfully exposed the contradictions of even attempting such work. And by exposing the flaws of the event, while simultaneously platforming incredible African and African heritage architectural talent, Lesley is creating a space for controversy, discussion and legitimate future-building.

By exposing the problems on a global stage, we can look them in the eye and begin to move through them, informed and equipped with imaginative solutions. I feel lucky to have been brought into this world for a moment, to get a few days to drink up the deep work that radical architects have been doing for years. Yes – you have to pay to enter the Biennale and it is operationally exclusive in many ways – but the exhibitions are drawing from the making-space and thought-leadership happening outside, in communities across the world. Voices that have been marginalised in the global conversation are finally getting platformed in these elite spaces, and challenging the very nature of the space and exhibition doing so.

Something I remind myself of weekly is that to enable change we need a diversity of tactics – whether it’s the controversial stunts of Just Stop Oil or the councillors lobbying tirelessly to change the specific wording of policy. I have been exposed to a new tactic, utilising a highly visible art event to mainstream radical conversations to wealthy audiences and the money that comes with it to resource the progressive voices in collectively imagining a better world. Props to Lesley for carving out this space.

Dancing Before the Moon was commissioned by the British Council for the Biennale Architettura 2023.

What can you do?

Some reads that inspired the British curatorial team that I’ll be digging in to:

- Art on My Mind by bell hooks

- Questions of Cultural Identity by Stuart Hall & Paul du Gay

- Changing the Subject: Race and Public Space – Mabel O. Wilson talks with Julian Rose

Keep up with what the curatorial team do next:

- Joseph Henry: Mayor of London Culture & Creative Industries Unit

- Meneesha Kaur Kellay: Senior Curator, Contemporary V&A

- Jayden Ali: Director of JA Projects and Educator at Central Saint Martins

- Sumitra Upham: Head of Programmes at Crafts Council

Connect with groups re-imagining how domestic buildings can nurture thriving communities and ecologies in Britain: