As a movement that dates back to the early 1990s, Afrofuturism has gained renewed momentum over the last 30 years. It has permeated various forms of popular culture including film, television, music, and also helped inspire a renewed interest in Black speculative fiction.

The term can be traced back to Mark Dery’s 1994 essay “Black to the Future”, although he was one of many scholars, writers, artists and authors considering its themes at the time.

In contemporary culture, Afrofuturism is a liberatory cultural phenomenon; both a philosophy and history exploring the intersection of African diasporic culture with science fiction and technology.

Given the growing dystopian state of the world, I have started to engage more fully with Afrofuturism to restore a sense of hope, and to support my own reimagining of new and better realities. Afrofuturism has allowed me to explore themes that interlink Black womanhood, home and questions of our geopolitical past, present and possible futures. More recently, it also has spurred me to explore this through art which is why I jumped at the opportunity to see Sonya Dyer’s Three Parent Child exhibition at Somerset House.

A step into Past Futures

Three Parent Child is the final chapter of Sonya’s artworks trilogy, Hailing Frequencies Open (HFO). To explore the limits of space travel, in her works, Sonya weaves the seemingly disconnected universes of Star Trek and the legacy of HeLa cells, the first immortalised cell line which was taken from Henritta Lacks without her permission while receiving treatment for cancer. They have since been used in countless significant scientific discoveries.

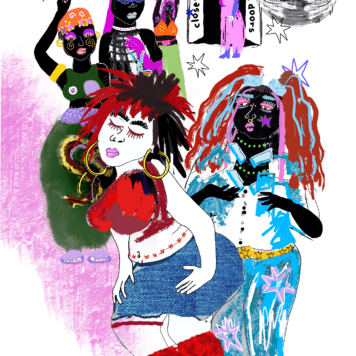

Pushing the boundaries of science fiction and speculation, Sonya uses the exhibition to explore the neglected stories of Black women in mythology and science, while questioning what their future role will be.

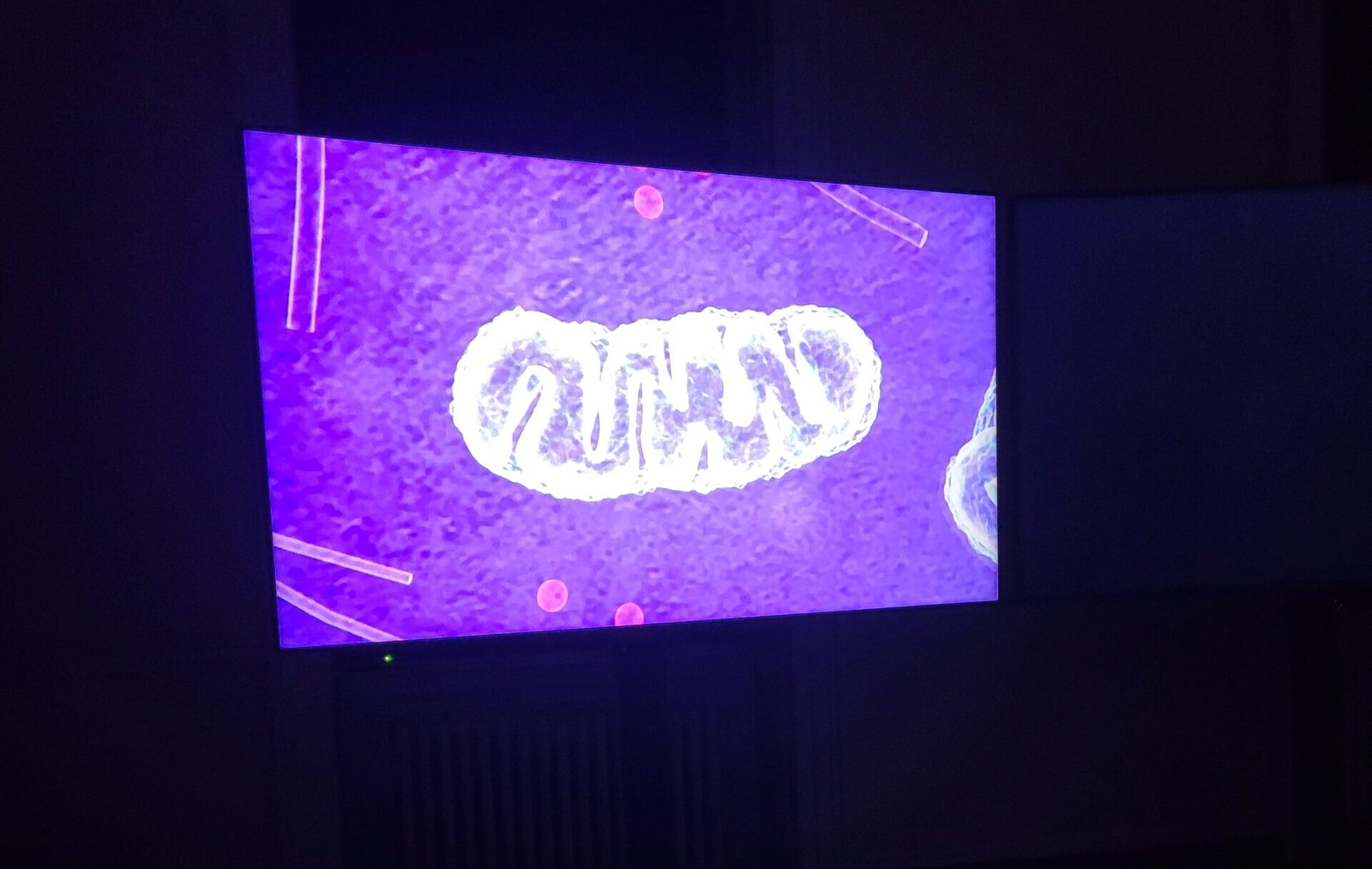

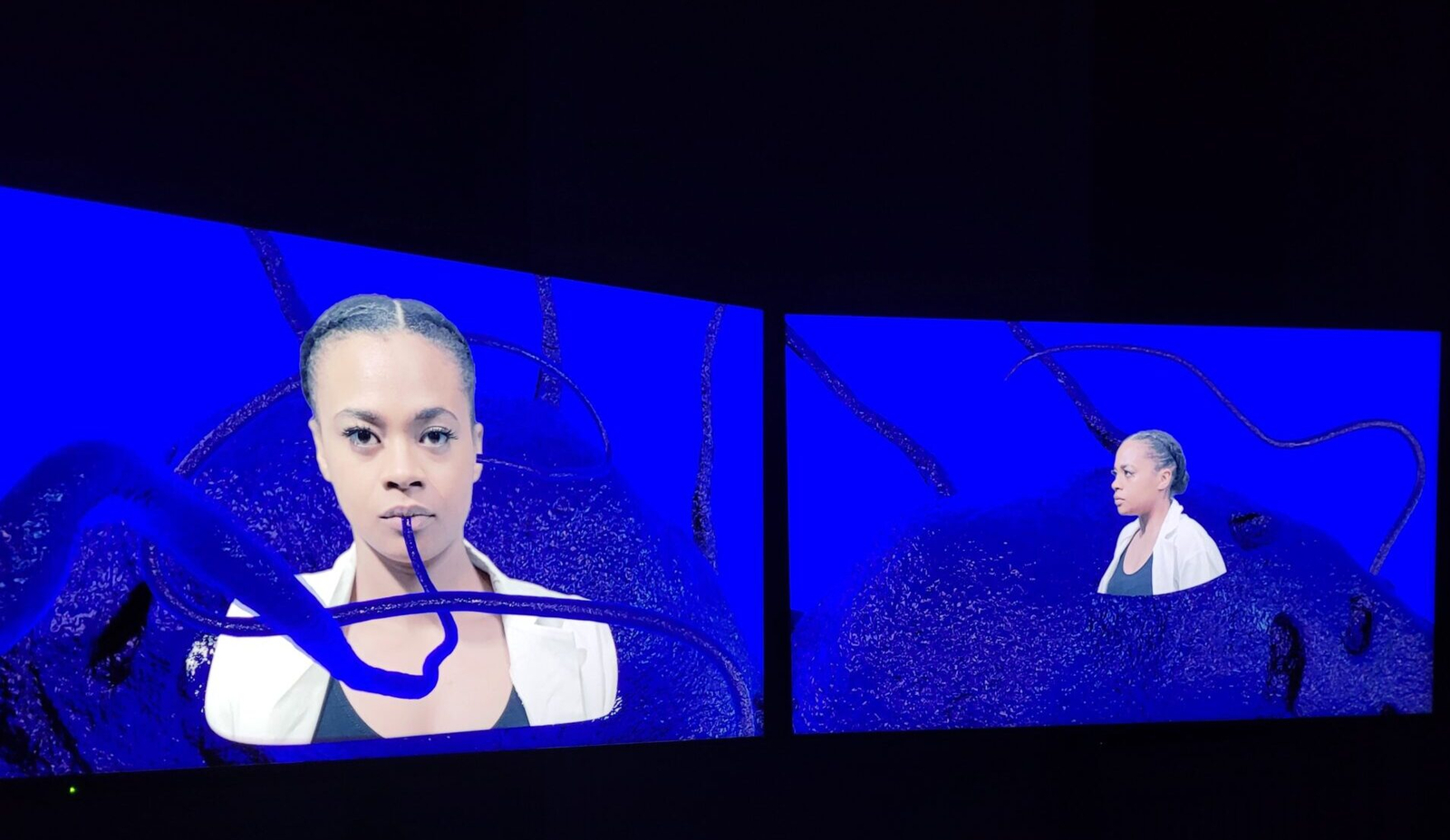

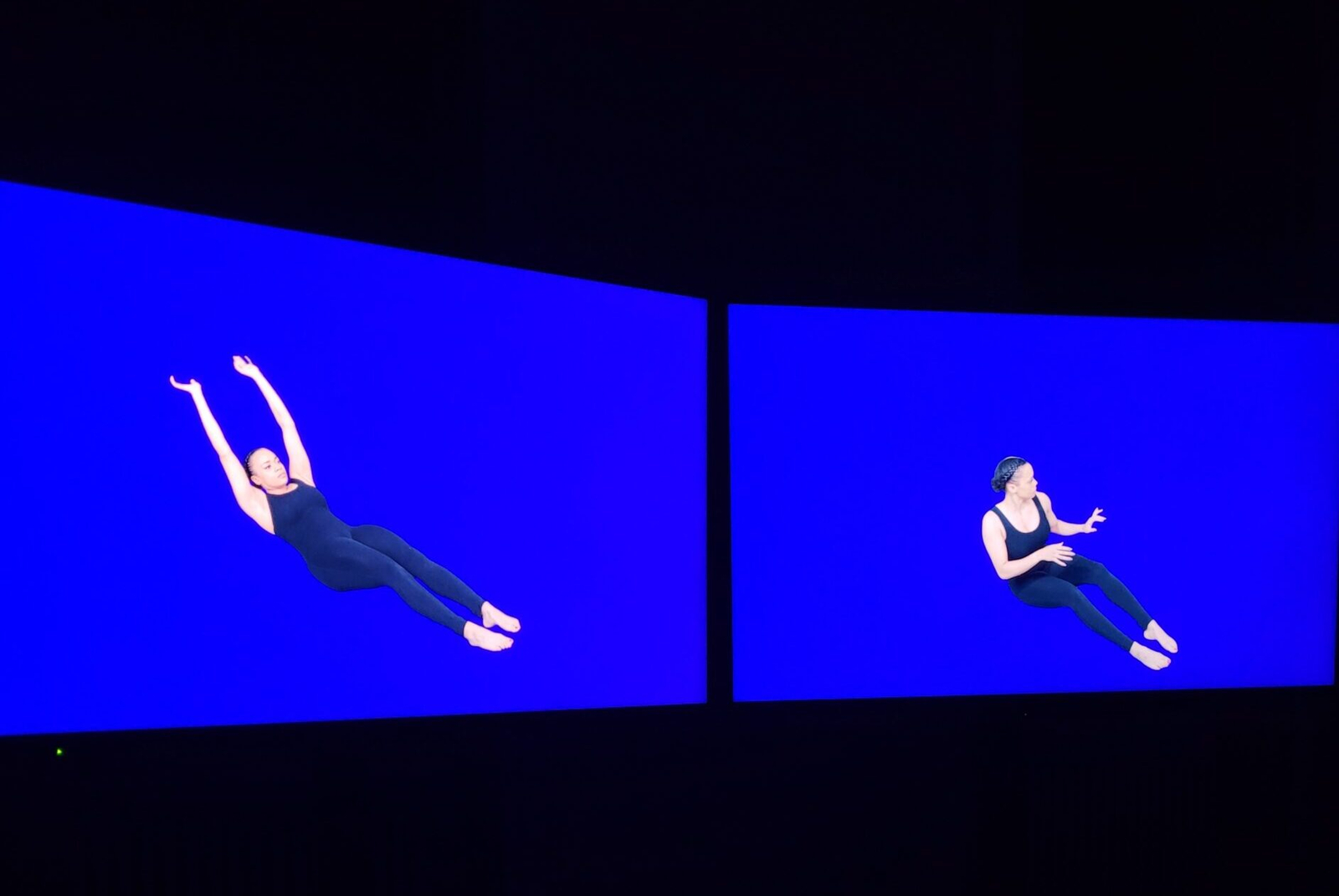

As an exhibition, Three Parent Child features two parts. The first is made up of images that move between two screens to create a film that centres the character of Andromeda, who shares her name with an Aethiopian Princess in Greek mythology. In the film, Andromeda seeks to return home after unexpectedly finding herself in a science lab, where she comes across a rogue mitochondria (an element found in our cells that are known as ‘powerhouses’ as they generate energy) named Lucy.

I entered the three River Rooms of the Somerset Studios not quite knowing what to expect. The first thing I noticed was the large black sculpture (which I later realised is Lucy), engulfing all three rooms and the two screens projecting images of Andromeda.

I hear a calming hum before the film starts. The film appears to be on a continuous loop, showing the link between Andromeda and Lucy, and how their stories emerge as one.

Even though this is the first time I have explored speculative fiction outside of film and books, this story and my conversation with Sonya is one familiar to me as a young Black woman. I left the exhibition piecing the narrative together, excited to ask Sonya all my burning unanswered questions. When Sonya and I speak, it is with candour, humour, relevant digressions and shared cultural idioms.

We reflected on how the use of art can create stronger narrative connections to highlight the futuristic qualities of Black women. Sonya tells me that the HFO project has been a work in progress since 2015, existing in different iterations until she could shift her practice into making objects. At its core, it explores ideas around monumentalism – in particular, interrogating who it is that gets to be monumentalised.

Sonya reveals that, like me, ever since she was a little girl, she’s always been into sci-fi “It’s informed a lot of my process and work now.”.

We bond over a common misrepresentation of Black girls and women in all forms of art, and especially in films where our stories seem to exist on the periphery. In comparison, from the way she recounts the hours she spent watching sci-fi, and all the different films she effortlessly reels off, I can tell that watching the genre made her feel seen.

We chat about how often Black women are so often unwillingly cast into the role of the ‘sidekick’ – and it’s this reflection which brings us back to discussing her work. “I am interested in making work that gives Black women characters agency,” Sonya says – though in spite of this, it’s not so much a conscious decision. She’s just making the kind of art she wants to see. “I just can’t imagine not centering Black women,” she tells me.

Black women at the centre of future imaginaries

I grew up watching Star Trek, Star Wars, X-men, Misfits and Doctor Who. I also loved reading the Animorphs and Hunger Games series – really, anything that was dystopian and futuristic which encouraged me to consider the spectrum of realities I could exist in.

I might not have fully realised it at the time, but I now see how important it was that I saw characters such as Martha Jones in Doctor Who, Black people who made it into the future and into our futuristic stories. It made me realise that our stories were not always those of suffering and hardship, but of adventure and wonder – lots of unrelenting, fulfilling joy.

Three Parent Child epitomises the core idea of futurism, linking legacies of different Black women from across our cultural references. However, while I was watching them unfold in the exhibition, their detail made me wonder whether some of Sonya’s references came from closer to home.

“I come from a long line of futurists,” she explains when I ask about the exhibition’s connection to her own Jamaican background. “My ancestors chose to pass down knowledge despite at the time not knowing if there was a future for their offspring.”

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

It is clear that, although many of us view our interests around futurism as a nerdy pastime, Sonya and I see it as a militant belief that the future is a thing we have our place in.

Sonya is also influenced by brilliant writers like Octavia Butler and Alice Coltrane. “I am so thrilled that our elders are finally getting their jewels!” she says. “It has taken a long time, but I still think it’s happened at the right time.”

I see this too, both from within the art world and the public more widely. This is reflected in the theme of this year’s Black History Month, ‘Saluting our Sisters.’ Now is the time to be paying homage to the Black women who had their contributions ignored, ideas appropriated, and voices silenced.

Soundscapes

Lucy is presented in the exhibition as a large-scale sculpture that mutates and transforms across the three exhibition rooms. Lucy is the most recent sculpture Sonya has created, following on from her previous exhibitions, all of which are named after the three enslaved women, Anarcha, Betsy and Lucy, who were experimented on by 19th-century gynaecologist James Marion Sims, considered the father of modern gynaecology.

“My friend called Lucy a violent intersection into the work – and I think that’s right. Lucy takes up too much space and snakes around the room,” she tells me. When designing Lucy, Sonya felt it was important to portray that the character wasn’t intimidated by the space she would eventually be shown in. “Instead I saw it as an opportunity to use the architecture of the space to subvert this idea of intimidation”. In this way, the exhibition physically determines a space for Black women in history and in the future.

In the exhibition Sonya employs different sensory mediums. Walking through the exhibition, we are also surrounded by the sound of Lucy’s disruption. These include vibrations, squeals from cells growing, transmissions, morse code in high pitches and compelling conversations between scientists, as the cells grow and move around us. We also hear Andromeda, made up from sonic scapes of Sonya’s past and future.

The sounds of cells moving under microscopes, especially as the sounds were recorded in the labs at King’s College London, root me in my university experience – creating the playlist which soundtracked the hours I spent doing coursework.

Like myself, Sonya has also been fascinated by these sounds. “I could hear the potential in these sounds,” she explains. “For the soundtrack we layered them to create a sense of otherworldliness, but also to connect the exhibition to the world of science. I wanted to bring in the environment that the cells were from and highlight their action potential (a change in energy),” she reaffirms. I think the importance was to centre the significance of these cells within science, and the discoveries and treatments they have led to.

Through Lucy, Sonya takes our power back in the exhibition. Through Lucy, she imagines a completely different reality where Black women are the source of power – we create it, transform it and embody it.

Speculations

Throughout her exhibition, Sonya illuminates a shift of power dynamics through space and time. In doing so, she moves away from reflecting Black women’s current reality.

The exhibition allowed me to understand that there are things that happen to me as a Black woman that I cannot explain in this realm, but can imagine in another. This much more positive and hopeful way of thinking reminds me why I love speculative fiction – especially when Black women are centred in this version of the future.

Sonya smiles after I tell her this. “It’s not my job to reflect the current reality. If we cannot project, imagine, or conceive of different power balances and futures, then they will never be born.”

It is clear through her work that she is interested in reclaiming collective imagination. “There is no point theorising about Black womanhood in an abject way, dehumanising us,” she says. “If I want to make Black women progenitors of the future, I can do that”. I felt a strong sense of hope and inspiration when Sonya shared this with me, because it reaffirms that there are no longer any rules in how we imagine and reimagine our stories – especially our futures.

Finding our way back home

This exhibition caught me off guard as it made me consider how love is so central in preserving Black women’s legacies. Sonya tells me this was intentional and was impressed upon her by the scientists Dr Clare Benson and Abduallah Erikat that she worked with for months while undergoing research for the exhibition.

They also made it into the show. In the short film Andromeda overhears a conversation by two scientists. They discuss that despite the history of HeLa cells, love and care are central to their preservation (and by extension this galaxy and new reality).

“The scientists were open and brilliant and were the right collaborators,” Sonya asserts. “Abdullah is a Palestinian man who has such a particular appreciation for life and for the HeLa cells he works with. I’m very thankful to them both.”

The amount of love poured into the entire process of the exhibition made me echo Sonya’s feelings of gratitude, particularly given the history of the HeLa cells, their theft and disputed significance in the field.

“I did not ask them (the scientists) to talk about love,” Sonya tells me. “It came up through an organic process of them coming to the studio and us getting to know each other.

Despite this embedded message of care and love, Sonya welcomes everyone to take what they want from this exhibition. “When Black women make art, there is alway a demand for an autobiography especially when bodies are involved,” she says. “I have a strong urge to challenge that, because white peers don’t get asked these questions.”

Sonya’s also wary of people assuming that Andromeda is meant to be a representation of herself. “Andromeda is a character I created from all these influences, from Tatianna to the scientific collaborators. My instinct is to resist talking about the work as though it’s autobiographical because this is not really what I’m trying to do. I get bored of myself very quickly!”

Realising that Afrofuturism exists in the present was the greatest gift Sonya’s exhibition gave me. It made me realise that its potential should not just exist in films, or art, but in our realities right now. Moving forward, I am excited to see more art that reflects this collective imagining, in a way that is interdisciplinary and highlights the Black community’s potential in all of life’s elements, from something as large as a galaxy, to something as small as a cell.

What can you do:

Watch

- Sonya Dyer’s interviews and other parts that make up the trilogy Hailing Frequencies Open

- Star Trek: The Original Series

Read

- Edge of Here by Kelechi Okafor

- More Perfect by Temi Oh

- What is Solarpunk?

Do

- Engage with science fiction through organising, all forms of organising are science fiction.

- Join a local community group or initiative to imagine a better future for all.

- Promote the work of Black writers, especially Black women writing science fiction

- Find out more about Sonya Dyer and her works here