Jay Price is a London-based artist whose work speaks to the marginalisation and neglect disabled people face. Having already exhibited all over the world and received a Masters from the Royal College of Arts, Jay is an established artist whose perspective adds to the necessary and continued evolution of the arts industry. They have just received the Adam Reynolds award, which they will use to develop their piece, ‘The Mine’ which will virtually immerse its audience in the harsh reality of our present society structured around ableist ideologies.

We caught up with Jay to discuss how they discovered their chosen medium, their experiences of artistic institutions and to discover why they still so fervently believe in the transformative power of art.

Can you introduce us to your practice and your journey as an artist?

I started as a traditional photorealistic artist primarily working in drawing. That led me to intaglio printing and etching, and the history of printmaking stoked and solidified my love affair with the medium.

While I was studying, I had my first psychotic break and the onset of schizophrenia. It was a very public and embarrassing experience and, to cope with it, I threw myself into my work. But my existing style didn’t feel right; I wanted to express my experiences that I now understood to be very different from other people’s.

I was lucky to already be working within the printmaking world, with so many brilliant processes and mediums. I started exploring the bones of print, thinking about rubbings and basic mark-making.

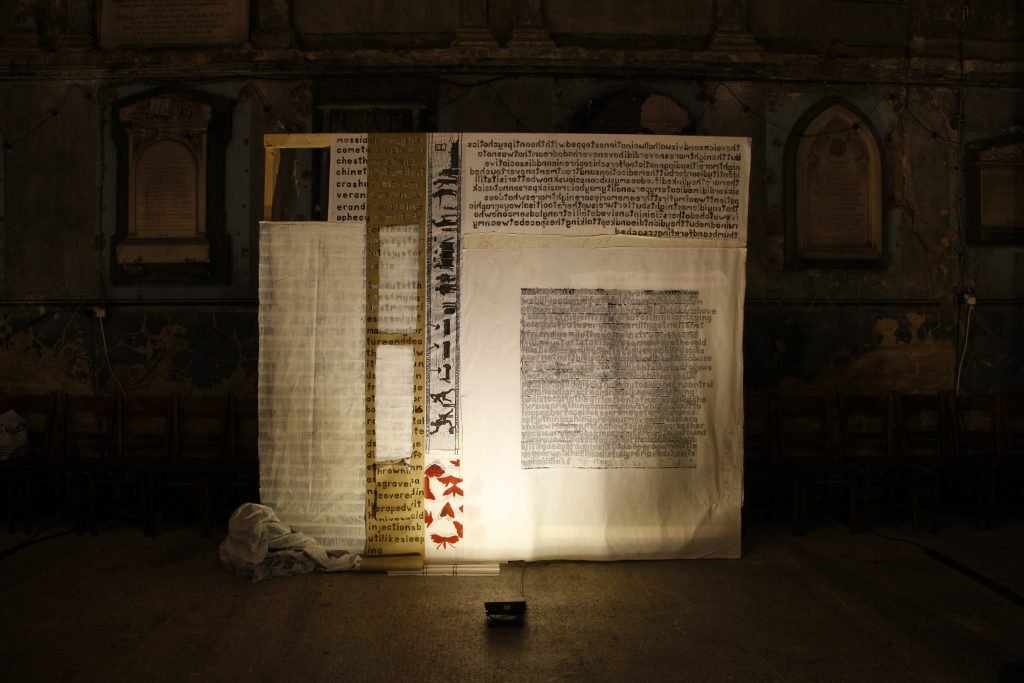

As luck would have it, my TV exploded. With some friends, I acquired a shopping trolley and pushed the TV, in the snow, uphill to the studio. I inked it up and printed it by wrapping it in fabric. Then I did the same to the trolley.

I found a huge relief in the process. It was more than just a system; it was an act of love: swaddling the object while also stripping it of its function. The series went on to include cars, minivans, grand pianos, buildings, and more. The images created were abstract, and similar to an inkblot/a Rorschach test. They were open to interpretation and there was no right or wrong answer.

From this explosion in my practice, I moved onto arduous, repetitive printing processes of smaller objects of personal significance. The processes continued to reflect the message and some deeper meaning, a confession. I like codes and hidden elements, and this remains a key part of my practice today.

Since then, no matter the medium, I always approach ‘making’ through the lens of a printmaker – process-focused. I pick the process and medium that is most appropriate to what I want to communicate, and I utilise the opportunity of theactof creating for feeding into the final message. I take a huge amount of satisfaction and reward in that, and it is a source of motivation at difficult moments.

You have a Bachelor’s degree from University for the Creative Arts and a Master’s from the Royal College of Art. What was your experience at these institutions like?

I had a very different but equally valuable experience at each. Both pushed me in the right way at the right time.

At UCA, I discovered craft and process. The onset of schizophrenia coincided with the start of my studies making for an interesting and eye-opening period. It was a fortunate happenstance to be immersed in a creative environment where alternative ways of thinking, approaches and dialogues were valued.

I came to UCA from a solely Catholic education. My mind was on a constant course of discovery, upending these prior dogmas. Knowing at this time that I was both non-binary and pansexual (though not knowing these terms existed yet) meant it was a period of liberation. As a result, my sense of self and identity as a disabled person coalesced, becoming the foundation of my creative practice.

The printmaking department was a small, tight-knit group, creating a friendly, supportive environment that verged on family rather than peers. It was a great way to begin my art career and get that high level of attention and support I needed while I experimented and tried new things.

The head of printmaking and tutor Randal Cooke(who sadly passed away last year) was brilliant, and never put up with any of my crap. I had a tendency to come up with big ideas and then bail out on them when it came to actually doing them as I got too nervous, especially as my work took teams of people, a lot of planning and logistics to make it work.

But he never let it slide. I said I’d print an entire car. And for weeks after that no matter what else I produced he’d say, “it’s okay, but I look forward to seeing the car.” He called me out constantly and I pushed myself enough that I discovered pushing myself was okay – even good. The worst that could happen would be that I failed. 90% of the lessons I’ve learnt in my career have come from failures and learning that failing isn’t losing.

How was your experience moving onto RCA?

I took quite a few years out between my undergraduate and Masters degree. Just after the former I had a serious, traumatic experience and couldn’t make art for a while. But eventually, the lessons learned in my Bachelors began to kick in.

I spent three years applying to the RCA. THREE YEARS! In the third year I eventually got accepted. Despite the triumph, I always knew I couldn’t actually afford to go, and so I began applying for a spectacular number of grants, bursaries, and funds. I was successful in getting three, including one from Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust (QEST), they made me a Garfield Weston Scholar, and between this and internal bursaries, my fees were covered for the whole two years. I’ve actually just joined the EDI group for QEST as they’re trying to diversify the types of people applying for funding and to make the experience more accessible.

RCA opened up my practice in such a profound way, but I didn’t start strong. I’d set it as my goal for so long that I was terrified of wasting the opportunity. To prepare for it, I dosed up on my medication in an effort to prevent any issues arising that would stop me from working and not risk any issues of psychosis.

This was only good in theory! The creative part of my brain struggled. To cover this up, I was reproducing old ideas and was at the bottom of the class in terms of quality. I was blowing it.

Four things happened at this point that changed the game:

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

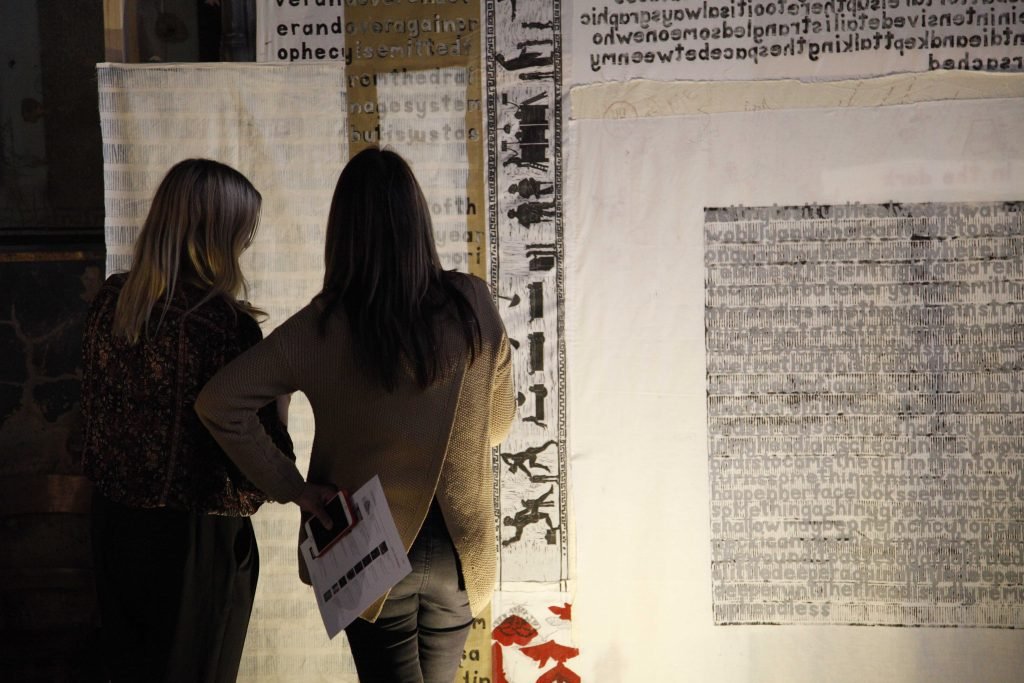

One: I went to the library both to get myself up to par in art theory and to translate the artspeak and intellectual content of certain lectures that might as well have been in another language to me. This was the moment I realised I would always strive to communicate in my work in a way that welcomed the largest number of people and didn’t exclude anyone.

Two: I decided to reduce my medication, eventually coming off it with the support of my brilliant partner.

Three: I wrote my Masters thesis.

Four: my work was brutally, and justifiably, criticised by a peer.

The invisible have no history. The mainstream effort to ignore or deny the existence of the insane throughout history has robbed those people of a past, present, and future.

I wrote my Masters thesis, called ‘Crowded Minds’, on outsider art and focusing on the ‘art of the insane’ tracking their place in the artworld and throughout history. I was searching for a family tree of strangers, looking for my place in history. I found that the invisible have no history, and the indomitable effort to ignore or deny the existence of the insane throughout history has robbed those people of a past, present, and future. Their work was devalued, as they were as people, and an art sensitive to a viewpoint and experience few will have the chance to know was and is being lost. I didn’t want this to be the case.

At this point during a critique my work was criticised by one of my peers. It was actually criticised by many of my peers but it was just the one that stuck in my mind, even now. They said my work was about a personal experience, and I claimed I was trying to use my experiences to demystify fallacies around psychosis, yet they didn’t see ANY vulnerable qualities in my work. This was a blow, and when I processed it I knew it was unequivocally true. I was being too safe and too detached.

I had kept documents during psychotic episodes. They weren’t diaries, but ways to analyse the experiences. I never wanted anyone to see them. But I read them. I reminded myself when I was tempted to go back into that state what it was really like; I reminded myself what I had lost, and that I was happy when I was out.

But that comment rang clear in my mind.

I made a handbound book. It had extracts from these texts. It was illustrated by soft ground etchings made by impressing stretched, laddered stockings onto a sanded steel plate with a thin layer of soft beeswax on. Laddered stockings felt like an elegant representation of the disintegration into different states of mind; of osmosis between two sides. Not a fast flood, but a gradual ooze.

Presenting that book for critique was the most terrified I’ve been in my career so far. But it was also the first time at the RCA that my work was praised. I went on to receive a distinction for my thesis and realised I’d finally broken through the block. All the students used to say you make bad work until Christmas in the first year. It took me a little longer, well, six months longer. But it was worth the steep learning curve for what I gained.

You recently won the Adam Reynolds award for your digital project ‘The Mine’. Can you tell me more about it?

I was awarded the Adam Reynolds Award (ARA) by Shape Arts, which is a residency delivered in collaboration with Hot Knife Digital Media, with the aim of creating a work that could be presented digitally. One of the key themes of my recent work has been exploring the possibilities of ‘dissemination’ and with this award having a digital focus, I researched engaging and experimental ways artists worked digitally through lockdown. It’s a really exciting and inclusive area and there’s real potential to make work that challenges the marginalising structures of the artworld.

Working with Shape is incredible as they’re a community of disabled professionals creating a platform for disabled voices and art which has a direct and hard-hitting impact on their audience. It wasn’t ‘pity’ gestures, it was enabling and in support of a powerful cause. I wanted to be involved. I applied and got accepted into my first Shape Open exhibition which then became my second and my third. I exhibited next to artworks that still haunt and empower me today. I felt so proud being connected to these shows.

Can you walk me through how a viewer will experience the work?

‘The Mine’ will be an app, downloaded to a phone or tablet.

We are working to try and make this as accessible on as many platforms and as many devices as possible. Your avatar will spot a basement along an urban street. As you stumble in, you’ll discover a memorial; a forgotten space, made under limitations, by and for forgotten people.

The memorial will thread together pieces of the history of disabled people. You’ll be able to explore with a torch, discovering objects, stained glass, artworks, graffiti and more, finding out information about each as you go. You’ll learn about troubling and horrific stories endured in the past and recent history, and uncover heroes, too. Some creative thinking will be needed to unlock the hidden potential of some of the interactive objects.

Can you tell me a little about your previous project, ‘Canaries’?

‘Canaries’ is a lightless chandelier. No light, no enlightenment, just a ringing of bells drowning out any voice that stands against that which is unquestionable. It highlights the undesirable role disabled people play as a warning beacon to everyone in society.

Disabled people bore a disproportionate brunt of the negative effects during the pandemic. Anti-mask and anti-vax movements imprisoned those with certain high-risk conditions in their homes, DNRs (Do Not Resuscitate Orders) were applied to disabled people in hospitals without their consent, and the recurring comment circulated that those who were dying were onlythose with pre-existing conditions and the elderly.

We saw clearly the value placed on disabled people’s lives, and it was mostly accepted by society, as it has never been any other way. Whether it is 1933 and the ‘Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring’, 400BC and Plato’s principles of selective breeding predating the use of the word ‘eugenics’, WWII and disabled peoples’ murders in the holocaust, or spiritual or religious beliefs claiming possession; excuses are easily found when one is looking for them.

But we are the canaries in the mine. The treatment of us foreshadows the treatment of more socially acceptable humans. People may not care about us but they should take heed of our plight, as next it might be someone they love, or even themselves.

What do you see as the role of art in changing perceptions and breaking stigmas?

I believe in art in a way I’ve never trusted anything else; and that belief is unwavering.

Art can move people to tears, provoke viewers to destroy it, indoctrinate people, liberate nations, and incite rebellion. I’ve seen it used as therapy and relief, and it speaks outside the restrictions of language, even, sometimes, creating it. I’ve walked in other people’s shoes through art (once actually walking in other people’s shoes), and enabling empathy is a strong tool to challenge ignorance and change perceptions. If you are part of a community that is persistently ignored, invisible and voiceless, then art is a heady ideal.

When platforms are not provided within the artworld for certain groups, when the art world lets us down – when it is outdated or elitist – that, for me, is where printmaking steps in to inspire, with its revolutionary potential as both art form and political act.

It’s lower cost, it’s reproducible, and it’s based on a history of mass dissemination, consumption, and bringing content to different groups outside of the lucky elite. It seems to me that when art has been revolutionary, the workings of that power are often overlooked. Print is often seen as a little brother of fine art, simply for the aspect of the multiple and lower prices – but these are its strengths. Print materials have had a far wider and more significant impact than most other artforms. While the art market is driving prices up I’ve rarely thought the price and the value of a piece lay in the same place.

Dissemination is a method of survival without a privileged source of income or the platform of a gallery. The affordable and the free becomes an act of defiance against a system to save the system. It infiltrates and introduces voices that would otherwise be excluded, and it makes art relatable and tangible to a wider group of people.

Art can change the world, but we need to build our own platforms to break down walls.

What can you do?

- Follow Jay and keep up with their work via Instagram

- Read more pieces on Art Activism HERE

- Follow Shape Arts and discover the amazing work by disabled artists they support.

- Listen to the Disability and… podcast which explores key issues in art by interviews with disabled artists and key industry figures.