As East and Southeast Asian Heritage Month rolls around for its third celebration, I’ve been thinking a lot about the theme for this year: Roots | Routes. Specifically (and because naturally, we tend to make things about ourselves), I’ve been thinking about what it actually means for second or third generation folks to trace their families’ journeys and examine them in the context of their own personal identities.

This feels especially critical for people of mixed heritage, or people who feel disconnected from their heritage. Like many, I struggle to connect the frayed edges of my family history, and I feel torn between delaying, not knowing how to get stuck in, and the urgency that comes with the realisation that family members are not getting any younger.

Connecting the dots

About three years ago, I started collecting stories from Instagram followers about their grandparents, prompted by a conversation I had had with my mum about her mother and her resilience during the aftermath of the American/Vietnam War. Then, in 2021, I worked with some dear friends on the Land, Sea & Stars project, a digital storytelling exhibition exploring the impact of displacement from Vietnam on the second generation British Vietnamese diaspora. The work made me feel more connected to my identity through the discoveries and stories of other people in my community and I felt emboldened by the impact it had on my fellow co-founder, Amy, who interviewed her sister, Mimi, about the family’s escape from Vietnam.

“After the founding of besea.n in 2020 and with a small daughter in tow, I realised that I had neglected a big part of who I was and I needed to discover the root of my disjointed upbringing,” Amy tells me. “I had always struggled to navigate the disconnect I felt from my ESEA heritage and the Land, Sea & Stars project was a way for me to process my family history.”

She continues: “As Mimi was just a child when Saigon fell, it was almost an adventure by her account. I am the youngest member of the family and because of that, I realised that she was doing what my family had always done, protecting me from truths that perhaps they themselves were not ready to face.” A part of me also wonders if it’s easier for those who are less connected to the events to ask the probing questions, which is certainly something I’ve seen in my own family. Survivors often want to focus on the future, not dwell in the past.

“More than anything,” Amy continued, “that experience taught me that I am still very much on the start of my journey to understanding where I sit in the world. Whatever my sister left unsaid actually showed the gravity of what an unspeakable experience it must have been for my family. I continue to find answers and heal slowly but I am grateful for Land, Sea & Stars for not only paving the start of that journey but connecting me with other people impacted by the American Vietnam War, whom I feel inextricably bound to.”

I, too, feel a strong bond not only to people whose families were impacted by that same war, but also to anyone displaced as a result of conflict or hardship. Through my work with besea.n, I have also been lucky enough to meet and collaborate with many people whose families moved to the Britain for a better start, and writing about it along the way.

Migration stories: documenting the fabric of British society

When I saw the announcement about Heart of the Nation, a new exhibition highlighting the foundational contributions of migrant healthcare workers to the NHS in celebration of its 75th birthday, I was immediately interested in the role of the children of healthcare workers in gathering up their parents’ stories. The exhibition, which will tour Leicester, Leeds and London this year, also has an online component.

I spoke to Lee Appleton, who describes herself as an English Filipina artist born and bred in London, about what it was like documenting her mother’s story. Her mother, Mae, who, like many, came to the UK in the recruitment drives in Southeast Asia in the 1970s, used to put on traditional folk dances for patients on the wards, in addition to her nursing duties, which kept her extremely busy.

“These stories were already familiar – I’d heard them over the dinner table – but somehow, through the interview process, they just became richer and more detailed,” Lee says. “They even managed to source bamboo as a prop from a carpet shop in Basingstoke!”

The anecdotes come through via WhatsApp over a shaky internet connection in the Philippines during their fiesta, which, from what I can tell, mainly involves being called to eat about 20 times a day, meaning our “interview” actually takes place over the period of a few days. It’s actually a lovely way to conduct an interview, albeit somewhat indirectly, and I imagine Lee stealing away for five minutes here and there in between celebrations and enthusiastic lolas force-feeding her homemade delicacies.

Lee had wanted to do the project since she was in school, she explained, with the aim of exploring her own identity through her mother’s migration story. She started collecting photos for a school project and then moved onto producing artwork based on identity. A sense of urgency was ignited at the beginning of the Brexit campaign, when it seemed like media pundits and government ministers alike were obsessing over the term ‘foreign-born nationals.’ She was spurred into action to create the Instagram page, @pearlsofthenhs. The account was subsequently picked up by the Migration Museum, and Lee’s mother, Mae, was asked to share her story.

“I just wanted to give more of a face to immigrants,” explains Lee.

Having written in the past about how the British media tends to dehumanise migrants and think of them as a monolith or a number rather than as actual people, this point struck a chord with me. When we listen to migration stories, it’s critical, says Lee, to “step into that picture – step into their shoes and try to imagine how it must have felt.” What did the temperature feel like when they stepped off the plane? Was anyone there to meet them? What kind of clothes did they have? Who were their very first interactions with?

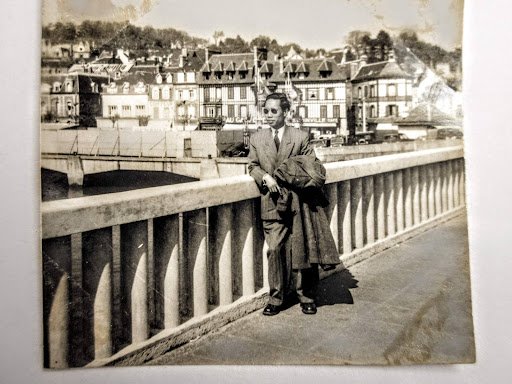

I think about this a lot when I look at a photograph of my grandfather that one of my uncles shared with me recently, in response to my quest for more family history. It’s a black and white photograph taken of my grandfather in Paris in 1953, standing on a bridge wearing a style of sunglasses still fashionable now, a two piece suit, and with a heavy-looking overcoat draped over his arm. How did he travel? How did the climate feel after the humidity of Saigon? Where did he get the coat from? Were people polite to him? I have no memories of my grandfather, this distant, overseas figure who died in Saigon when I was still in single digits. So all I can do is speculate and ask my relatives what he was like. They often give me very simple answers:

“Un mandarin.” (in French, a person who is both important and influential in their milieu, particularly in academic circles).

“Cerebral.”

“Disciplined.”

Needless to say, I often find myself trying to fill in the blanks.

Although he lived his entire life in Vietnam, my grandfather had been brought to France briefly for administrative training under the French colonial government. Both erudite and multilingual, he was a civil servant and an aerospace lawyer who would eventually end up working for the government of South Vietnam. Not bad for a man who grew up penniless in Northern Vietnam, provided with a free education by Catholic missionaries. According to my mother, he also somehow wound up attending Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation on that very same trip – but that’s a story for another time.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

I made a long overdue return to Vietnam in December 2022, reconnecting with family for the first time in several years. I made contact with more distant family members I had never spoken to, collected photographs, visited several family burial sites, and asked endless questions, making do with French and with my poor Vietnamese. Often, the replies that came back to me were fragmented, perhaps not what I had hoped for.

Uncharted waters

The process of documenting family history often requires a tremendous amount of resolve and emotional resilience, especially as you navigate subjects you may never have broached before with family members. I spoke with Suyin Haynes, whose mother Linda also shared her story as part of Heart of the Nation, after having previously participated in the 2021 ESEA Heritage Month exhibition on a similar theme, curated by Becky Hoh-Hale, Ingat-Ingat. It can be very difficult to bring up the past with our elders, especially on the darker side of migration struggles.

“They might not see the value of that history,” explains Suyin, “and that is perhaps a product of being forced to assimilate and being told their histories aren’t valid, in whatever way that kind of racism has manifested.”

It would be naive, of course, to assume that every migration story was a great adventure and nothing else. Themes of racism come up frequently throughout the Heart of the Nation exhibition, and resurface in my conversations with Lee and Suyin. Lee feels a tension between wanting to safeguard her mother – after all, this was in the age of #StopAsianHate and COVID hostility – and to make the stories heard far and wide (at the request of Mae herself). Suyin noticed, during the “interview” and discussion process, that the exact verbiage of racial slurs seemed to stick out, even 50 years later, even when other details, perhaps more joyful ones, were somewhat fuzzy.

However, it can also be hard not to trigger or upset, especially as many things were said in the past when conversations about racism didn’t really happen as they do today. Lee had to take her cue from her mother, even when she had her own personal opinions on what had occurred.

“Why push that on her if that wasn’t her experience? My interpretation of it is that it was racism, but why put that on her?” she explains.

Lee’s mother, Mae, often said things like ‘We just kept our heads down, we didn’t ask questions.’ While this has helped Lee appreciate the resilience and work ethic that saw her mum through challenging times, to see the same sentiment echoed 50 years later during the COVID-19 pandemic, contributing to the disproportionate deaths of Filipino healthcare workers, was a hard pill for Lee to swallow. She’s grateful, however, that there’s more support for Filipinos arriving in the UK through the work of organisations like Kanlungan Filipino Consortium.

My ongoing efforts to trace my family’s migration story have led me on my own journey of self-discovery; in fact, I often consider it to be a lifeline in a time where I was at risk of suppressing or at best totally ignoring an identity that I’m now fiercely proud of. I ask the same of the people I interview – how has this process impacted them?

“I am 48 and still don’t know how I feel about my identity,” admits Lee. “It’s in every decision you make, from what you’re going to wear to what you’re going to eat. It’s alway there in every fibre of your being. And I constantly feel like I’m not enough of one or the other. And because I’m focusing so much on my mum’s story, I feel immense guilt that I’m not focusing on my dad’s story.”

I know how she feels. Guilt and conflict of loyalty to both “sides” often makes mixed people feel they have to be more objective when it comes to conversations about identity, rather than throwing their hat over the wall and embracing an identity that’s true and unique to them. However, I strongly believe that identity, in its fluid, ever-changing nature, is also something that’s curated by you, not branded on you at birth through your parents’ ethnicity and country of origin. Physical features or language are not the sole markers of cultural identity, but mixed people sometimes cling to the acceptance that comes with validation of being told you “pass.” Writing for TIME on identity, Suyin spoke of the dangers of the imposter syndrome that many have doubtless felt regularly:

“Sometimes I’ve felt uneasy or uncertain in fully voicing my identity as Asian, a hesitation rooted in the self-consciousness that I am less likely to experience the physically violent manifestations of racism in ways that others do. I’ve come to realise that that type of thinking is a form of invalidation, of erasure, of preoccupying myself with fears about Asian hate over much-needed Asian joy. Over the last year and through covering these issues more deeply, I’ve leaned into claiming – and celebrating – my polyphonic identities.”

For Suyin, although she and her mother were already close, participating in the Ingat-Ingat project meant that they had to be a little more disciplined; to sit down and carve out time to speak with intention about family history. “It solidified the sense of appreciation that I have for my mum, and the role that she plays in so many different communities and in so many different ways,” Suyin explains. “I always joke that she’s got a busier schedule than me.”

Ultimately, Amy, Suyin and Lee found that understanding this foundational part of their history and their families’ migration stories has helped them gain perspective on their own identities, struggles and privileges – and given them a thirst for more.

As we look to the celebration of this year’s ESEA Heritage Month, I encourage everyone to reflect on their family history, on the roots that built them and the often uncertain routes taken to get there. To ask the questions it may someday be too late to ask, and to tell the stories that deserve to be told, whether they’re simply being passed on to children or other family members, or made public.

- Heart of the Nation is on at Leicester Museum & Art Gallery until 29 October 2023, or available online.

- ESEA Heritage Month takes place every year in the month of September. See what’s on this year.

What can you do?

Don’t know where to start? Here’s some advice from some of us who have already started this journey.

- Document oral evidence

It will be less daunting for the family members involved to simply sit down and have an organic conversation. You may want to have some questions to structure or guide you, but it’s also important for you to feel an emotional engagement with the work through meaningful connection.

- Use visual aids

Objects can often evoke quite vivid memories, and, explains Suyin, it relieves the pressure on the interviewee to remember so many details on their own. Remember, you may be asking them to revisit things that happened fifty years ago!

- Let them guide the conversation

Don’t try to push anyone down a memory lane they don’t want to go down. Sometimes, you may need to remind yourself that your elders’ experience is not your own – you might have different opinions sometimes, and that’s okay.

- Be patient.

Things might not always turn out the way you expect, but that’s part of the beauty. At the end of the day, we should all take the advice of Lee’s mother, Mae:

“Don’t worry, darling. Keep trying.”

With thanks to:

Alicia Warner

Amy Phung

Becky Hoh Hale

Lee Appleton

Linda Haynes

Mae Appleton

Mimi Phung

Suyin Haynes

Vu Tam Quang