There’s a riotous energy in Haggerston’s Signature Brew pub as Bristol-based vocalist and producer Grove takes to the stage chanting “off, off, off, off with their heads!”. Their slogan is pointedly directed at both the monarchy and the country’s landlords.

It’s not long before this reverberates around the room, a mosh pit emerges, and the crowd lose themselves in the frenetic fizz blasting out of the speakers.

“Off with their heads” is about as punk a chant as you can get. But Grove’s set isn’t the typical hard-edged metal and clashing electric guitar that you’d expect from a punk rock set. Instead, the musician plays around with drum n bass, dancehall and metal. The eclectic sounds melt together into a hip moving, head rocking concoction of ecstasy.

The righteous rage in their lyrics and delivery is not only palpable but evidently contagious as it is eagerly lapped up and sung back by the crowd.

Grove’s performance is just one of the many that challenge the collective perception of a punk set over a long weekend in mid September. The vast majority of the audience are people of colour and they’re here to see Black and brown punk bands.

Now in its fifth year, Decolonise Fest is the only festival in the UK that is run by and for punks of colour. I’m here as a volunteer and I’ve spent the day switching between running the merch stand to selling tickets at the door. I’m scanning barcodes when I start chatting to founder of the festival, Stephanie Phillips. I mention that I’m writing an article on Decolonise and ask if I’d be able to chat to her about it.

The idea for Decolonise Fest was born out of an Instagram post. Stephanie, a writer and musician (who is one-third of Black Feminist punk group Big Joanie) put out an open call in 2016 asking people what lineup they’d like in a POC punk festival. She was immediately overwhelmed by the volume of responses.

There’s a break between sets and the crowd gathers around the bar to order drinks. Roars of laughter erupt as the festival-goers catch up with old punk friends and make new ones. On the stage, a new band begins to set up, and as the mics are being tested and guitars are tentatively strung, I make my way backstage to chat with Stephanie some more who has found a free moment in her unrelentingly busy schedule.

“About 25 POC in the punk scene turned up to our first meeting,” says Stephanie as we catch up in a dressing room that doubles up as a food pantry for performers and volunteers. “It was a bit of a consciousness-raising experience. I had the first festival only a year after in 2017 and we’ve been continuing from there really”.

I ask if she was surprised at the depth of desire for a festival of this kind. “I always knew that I wasn’t some sort of outcast or weird because I was Black and into punk. That there must be other people out there like me. I thought I found that through Big Joanie, but then I started thinking about how there must be more than three Black women that are into this music”, she adds, laughing.

Stephanie first started playing in punk bands in 2010, a time when there “wasn’t any conversation around race in punk circles and very few POC in the London punk scene.”

Over time, she says, the situation has changed quite dramatically. “It’s just amazing to see that there are loads of young people of colour in punk and it doesn’t seem to be a big deal for them”.

Stephanie has noticed that the new generation of punks of colour are much more likely to speak out on issues of representation and racism within the scene and wider society, which she says is thanks to the resurgence of movements like BLM. “There’s less patience for poor treatment,” she explains.

Self-expression is intrinsic to punk – but the irony that POC have been sidelined and stepped over in such a historically anti-establishment and rebellious community is not lost on Stephanie. It’s exactly why she invests so much time in ensuring spaces like Decolonise exist.

“There are a lot of people who have been saying we don’t need to be in the shadows anymore and we can express the whole of our being – not just one side here and one side there,” she explains before adding: “You can be your full self in spaces like this.”

As Stephanie and I chat, a band clamber into the backstage area before noticing us and apologising for having unintentionally walked in on our conversation.

They’re Whitelands, one of the younger bands on the lineup. They play shoegaze, a subgenre of alternative rock known for its dreamy soundscapes and drawn out lyrics. Majority Black, the four-piece band have faced prejudice navigating the scene and the music industry more broadly. I ask Jagun, the drummer of the band, if they’d be interested in speaking with me and soon I’m standing outside the venue with them in the chilly September night air.

“Industry reps take one look at the photo of our band and go ‘Black boys!’ ‘They do grime!’ Actually, we don’t do grime; we don’t do drill. We do shoegaze. But they just kind of think of us as just pissing around with instruments.”

Whitelands explain that finding producers who can cast aside their prejudices has been a journey. “You go in and they judge you on your profile. They don’t know how to work with us. We want that same sound as My Bloody Valentine but because of our skin colour, they assume we’ll make it a bit grime-y,” guitarist Vanessa and lead singer Etienne add.

Etienne mentions how it’s been common for labels to use Black musicians as songwriters for white artists. “Back in the 90s, The Veldt, [a Black shoegaze band from the US] had their stuff shelved by their label Capitol.”

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

I point out the treatment of RAYE, a singer-songwriter who last year took to Twitter to reveal her record label had been refusing to release her debut album for several years. “Yeah, it’s really fucking sad”, says Vanessa, “It’s exhausting, but you have to keep fighting.”

But amidst the struggle of navigating the music industry, the joy of playing at a festival like Decolonise is an unmatched feeling for the band. Drummer Jagun says: “It makes you feel proud. It feels crazy to say but there are people in that crowd looking up to us. We are now inspiring other people to be like, ‘oh shit I can do this too’”.

I head back into the venue as Saturday’s headliners Dystopia start their set. The all-girl rock group from East London are energetic and captivating. While largely still for the entirety of the performance, they enchant the crowd with their emo-tinged delivery and lyrics that speak to feeling empty from staring at screens but yearning for a fuller life.

Comprised of Abby, Amna-Janine and Ify, the band were touched by the supportive environment and positive energy of the crowd. “It was so beautiful and felt extremely personal. Tonight was just something special. I feel like we’re all coming from similar places, we all have a similar connection and understanding of our experiences,” singer and guitarist Amna-Janine says.

The trio, who were featured on FKA Twigs’ Caprisongs mixtape this year (the popstar heard their music and DM’d them on Instagram before they all went for a walk in Hackney’s Victoria Park), reiterate the importance of both feeling represented – and being that representation for others.

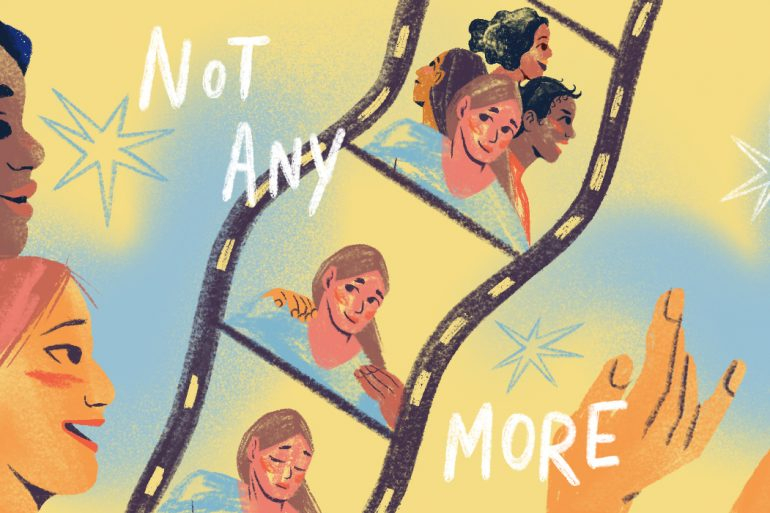

Ify, the group’s guitarist says: “We want to be the people and the faces we didn’t have growing up. We all listened to rock bands, alternative bands, and not a lot of them were people of colour or specifically people who looked like us. And so we made that for ourselves.”

Marcus MacDonald, a founding member of Decolonise, resonates with the feeling of having found an oasis of respite through the festival. “It’s like a sanctuary really. When I saw Stephanie’s Instagram call-out, I was really drawn to it. I was like, ‘yes it’s time to get away from the white punks’.”

Now 36, Marcus has been involved with the punk scene since being a teenager and in that time he has witnessed his fair share of ignorant and racist comments.

“I was squatting for a long time and in most of my houses I was the only Black person or POC even. I was used to it but as I got older I realised a lot of the things people were saying or doing were weird and problematic.”

The discussion of race issues inside and outside the punk scene would often be a contentious point for his self-avowed anti-fascist friends. He says they would routinely deflect from any racist comments by pointing out that they beat up Nazis. “That’s a big thing in punk, people often feel like they don’t have to look at themselves or their behaviour [because of their radical politics].”

Marcus, who is Queer, adds it was common to hear racist, abelist and homophobic comments on a routine basis and was once given a golliwog from an ex-housemate on his birthday. “They thought it was really funny. They also gave me a plate that they’d painted like a golliwog”, he tells me.

While acknowledging that many white punks are genuinely progressive, he admits that there are certain subsets of the scene that are stuck in their ways and hostile to change. “There’s some parts of the punk scene that have never changed and never will. There are others that have become a bit more open and they will come to Decolonise Fest.”

Some of those that aren’t supportive took it personally when Marcus started doing Decolonise Fest. “Me and another friend who started Decolonise got a lot of backlash from our old crust-punk friends who were like, ‘Why would you organise that? That’s so divisive. I’ve been anti-racist my whole life’. Instead of being really supportive, they saw Decolonise as an attack on them. I think it is really important to have Decolonise Fest to escape that.”

For co-founder Stephanie, the aim of the festival isn’t purely to platform POC punk bands but also be a home for Black and brown punks in both a literal and spiritual sense. “Decolonise is not just coming to a gig hopefully, it should feel like coming home. That’s the concept and idea. We’ll welcome you into your own home and get you to remember this space is yours too.” As band after band finish their sets to an electrified and roaring crowd, it’s hard to disagree.

What can you do?

- Follow the bands:

- Follow Decolonise Fest to keep up to date with the festival and any POC punk events happening

- Read Stephanie’s article for VICE on the bands taking British Punk back to its multicultural roots

- Listen to this podcast on Black Punk Rock and the history of African American punk rock artists

- Read this article by Dazed on the Black punk pioneers who made music history