“I was born a woman, but I never lived as a woman.” These are the words of Kim Bok-Dong, who prior to her death in January 2019, was one of the last surviving Korean ‘comfort women’ still waiting for an adequate apology from the Japanese government.

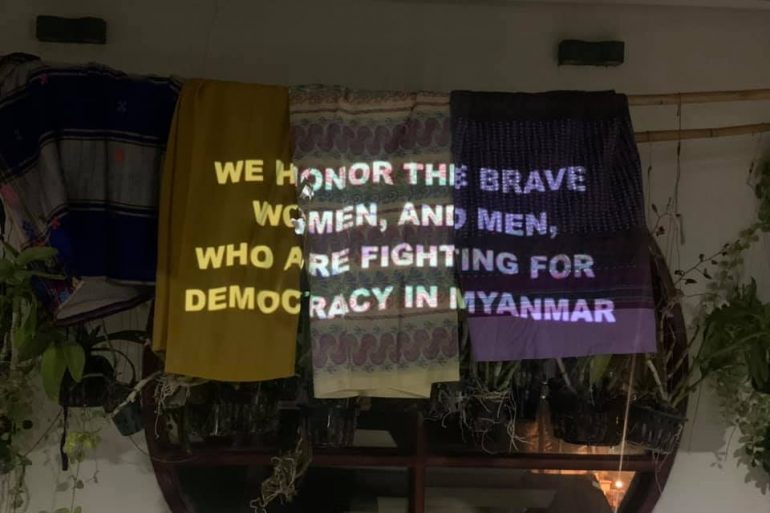

Her funeral was a rally. Mourners carrying yellow butterflies shivered for five days through sub-zero temperatures on a march to commemorate the woman who had dedicated her life to more than a 70-year struggle. Culminating outside the Japanese embassy in Seoul cries of “Japan must apologise” filled the air as others wept for the woman who died with hatred for Japan on her lips.

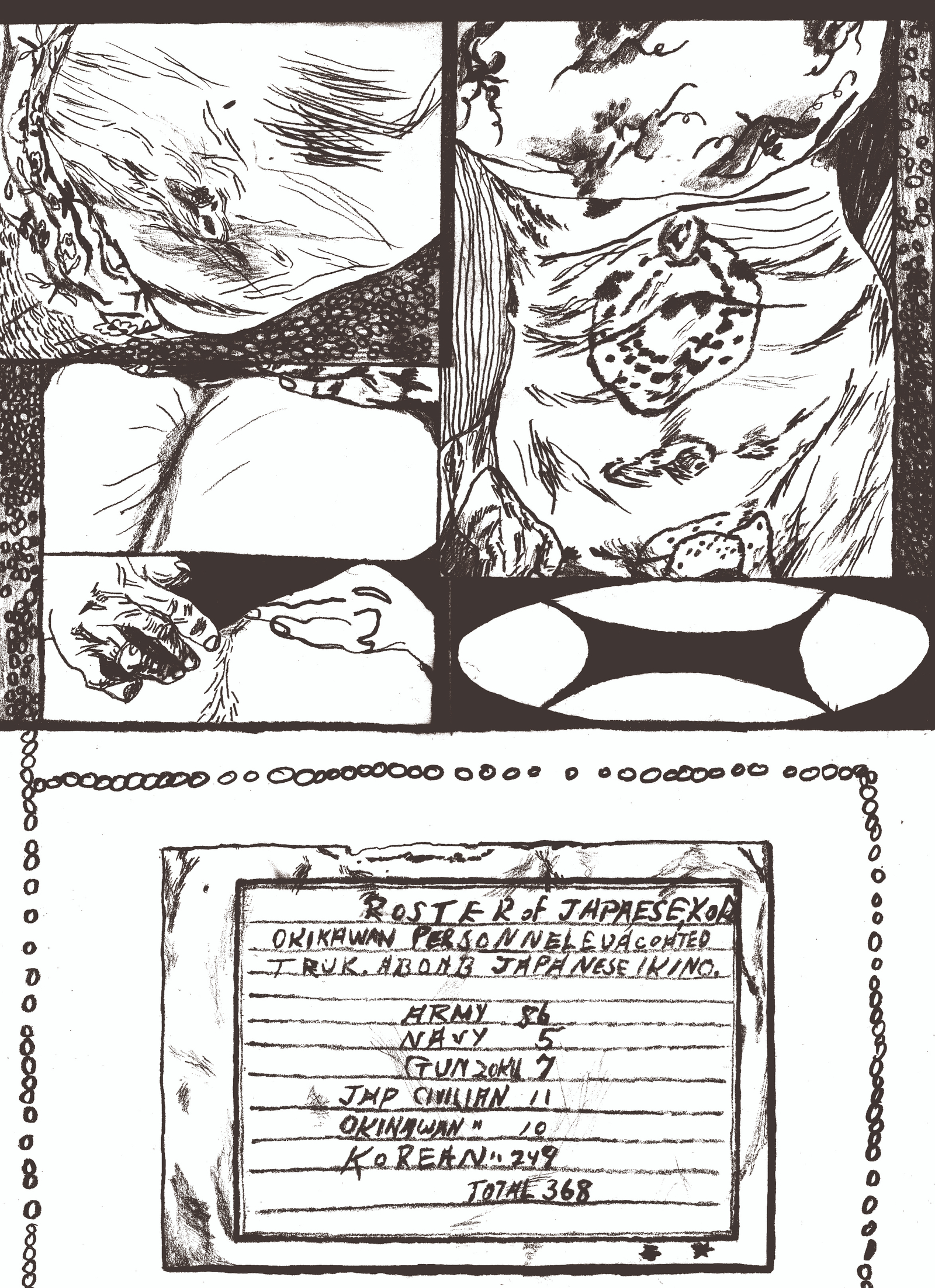

Kim Bok-Dong was one of a potential 200,000 so called ‘comfort women’, forced into militarised sexual slavery for the Japanese, and later American forces, during and after World War Two. At fourteen she was stolen from her home under the guise of going to work in a factory. She was told that if she resisted, her family would be harmed.

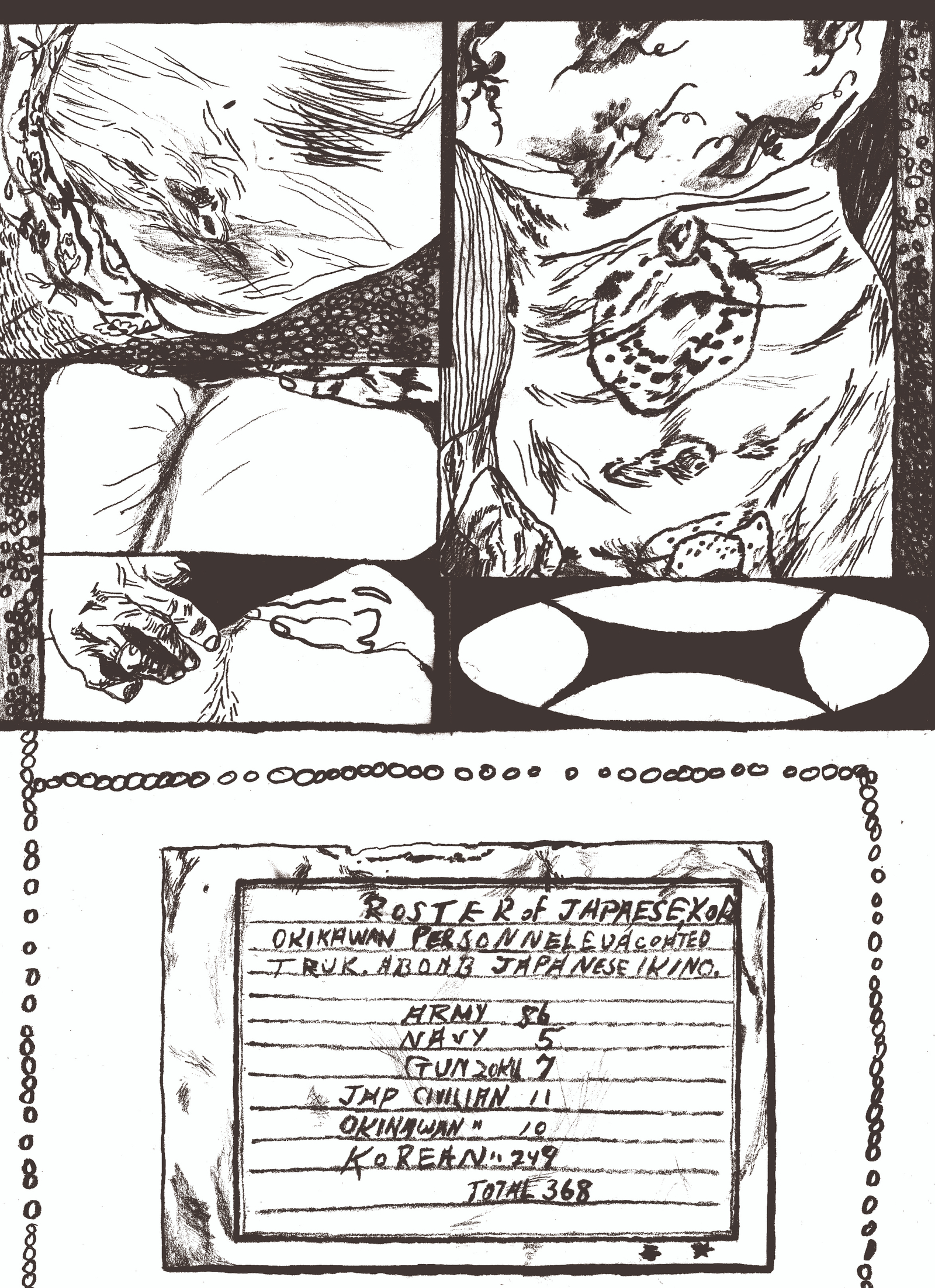

“On weekdays, I had to take 15 soldiers a day,” she once said. “On Saturdays and Sundays, it was more than 50. We were treated worse than beasts.”

One of the first women to come out against the Japanese regime and publicly tell her story in 1991, Kim and other women like her have since been in a battle of recognition with the Japanese government. Their voices have been lost amongst a barrage of male posturing and denial.

The ‘comfort stations’ were first set up by Emperor Hirohito after international outcry over the Rape of Nanjing, the so-called six-week period in which Japanese soldiers murdered and raped 50,000-300,000 people in a city in China. The introduction of the stations normalised sexual exploitation and the officers who implemented them well were rewarded for effective pacification of their soldiers.

In truth, ‘comfort women’s’ identities were taken out of a female, and indeed human, lexicon. Conceived of as a solution to male sexual appetite they were treated as an escape-like alternative to alcohol and listed as ‘military supplies’ when transported. Perhaps most disturbingly is Mark Driscoll’s theory of Sexuality in Necropolitics, in which he states that these women were made to endure such terrible conditions so that soldiers could familiarise themselves with death.

While attempts at reconciliation have been made by the Japanese government many of these women have never been able to truly gain back a sense of identity. The agreements reached in 2015, and later ratified in 2018, continually “fell short”, according to activists. The latest offer includes renumerations of 1 billion yen and a formal apology from the Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. However, with summits continually getting delayed due to worsening conditions between Japan and South Korea it seems as though these women will never be able to fully heal and move beyond their victim status.

“We won’t accept it even if Japan gives 10bn yen.” Kim told lawmakers in 2016. “It’s not about money. They’re still saying we went there because we wanted to.”

This attitude of government denial is a growing one in Japan, creating further barriers for ‘comfort women’ on top of their advancing age. Sentiment is turning more adverse as the post-war generation grow tired of apologist rhetoric. Toshio Tamogami, former chief of staff in Japan’s air force, who drew more than half a million votes as a candidate for governor of Tokyo in 2014, states “as a defeated nation we only teach the history forced on us by the victors”. His popular idea of ‘true’ history, denies the existence of the Nanjing massacre, stating that soldiers in 20th century Japan were liberators getting rid of European oppressors. While currently incarcerated due to violation of election laws his extreme views remain in wide circulation via several publications. Other prominent right-wing revisionists state that the ‘comfort women’ who have spoken out are fabricating or embellishing their stories for the benefit of the Korean government.

This burgeoning yet reactive view is evident in editions to textbooks and major broadcasting. Japanese liberal newspaper Asahi Shimbun retracted articles about wartime sex slaves it had run in the 80’s and 90’s. Earlier in 2019 Japan Times, the country’s oldest running paper, discontinued the term ‘comfort women’ after meticulous criticism from Abe. They instead released the wordy definition: “women who worked in wartime brothels, including those who did so against their will, to provide sex to Japanese soldiers”. The executive editor, Hiroyasu Mizuno told Reuters that he wanted to avoid creating feeling that the paper was “anti-Japanese”.

Even some of those who admit the existence of ‘comfort women’ adopt a universalist rhetoric. This sentiment relieves the pressure on the Japanese government to apologise. Historian Yuki Tanaka, writer of Japan’s Comfort Women states that ‘comfort women’ were part of a “pervasive pattern of worldwide male aggression and domination”. While the link between wartime atrocities and sexual violations is undeniable and specifically, U.S involvement in the ‘comfort women’ stations needs to be addressed, painting the ‘comfort women’ issue as a global phenomenon does not detract the fault of Japanese policy.

This kind of rhetoric continually silences the identities of female victims, excusing crimes against them as either fictional or normal. It is estimated that 90% of ‘comfort women’ died during the war. Now less than 23 registered survivors remain to hear what they believe is the appropriate apology by the Japanese government. With this continued rise of the right, growing tensions between the South Korean and Japanese governments and the escalating age of ‘comfort women’, it seems that Kim’s voice will unfortunately not be the last to be unheard.

—————————————————————–

Thoughts on Comfort Women

Rondi Park

Reading, listening, and watching the testimony of comfort women was not easy. They were howling, lamenting, full of resentment and still in sharp memory of their treacherous years. My original intention and emotional distance from the subject has vanished. I too was howling, lamenting and exploding with unsettlement. Shaking.

Comfort Women was a trigger word for me as South Korean. It was a word of political opinion, of hatred towards the colonial period, of a horrible history, of overloaded discussion on Korean news, of anti-Japanese and of hesitant shrugs and many “I don’t know’s”.

Strangely, I have not related this issue as what it is before. Dreadful human history that should never be repeated.

It always had something to do with Japan whom are undoubtedly responsible for this war crime. This side was more emphasized during my education than the side of fundamental reason of why this happened.

Patriarchal society that perceives women within a certain frame, not as human but just as a mere tool for men’s comfort and reproduction.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

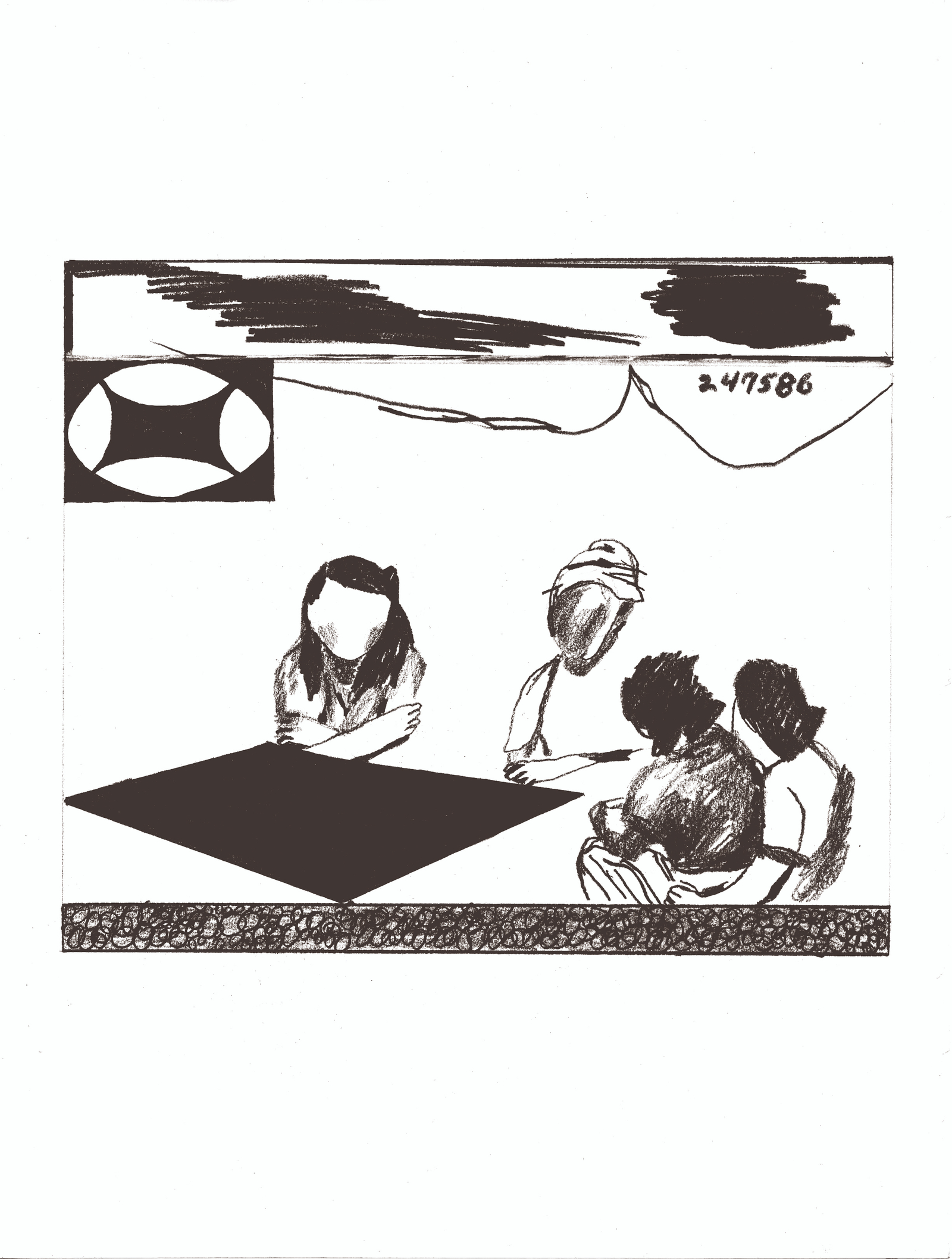

As deeper the research got, my concentration was wondering how I can transcend the situation without having to censor or edit anything out.

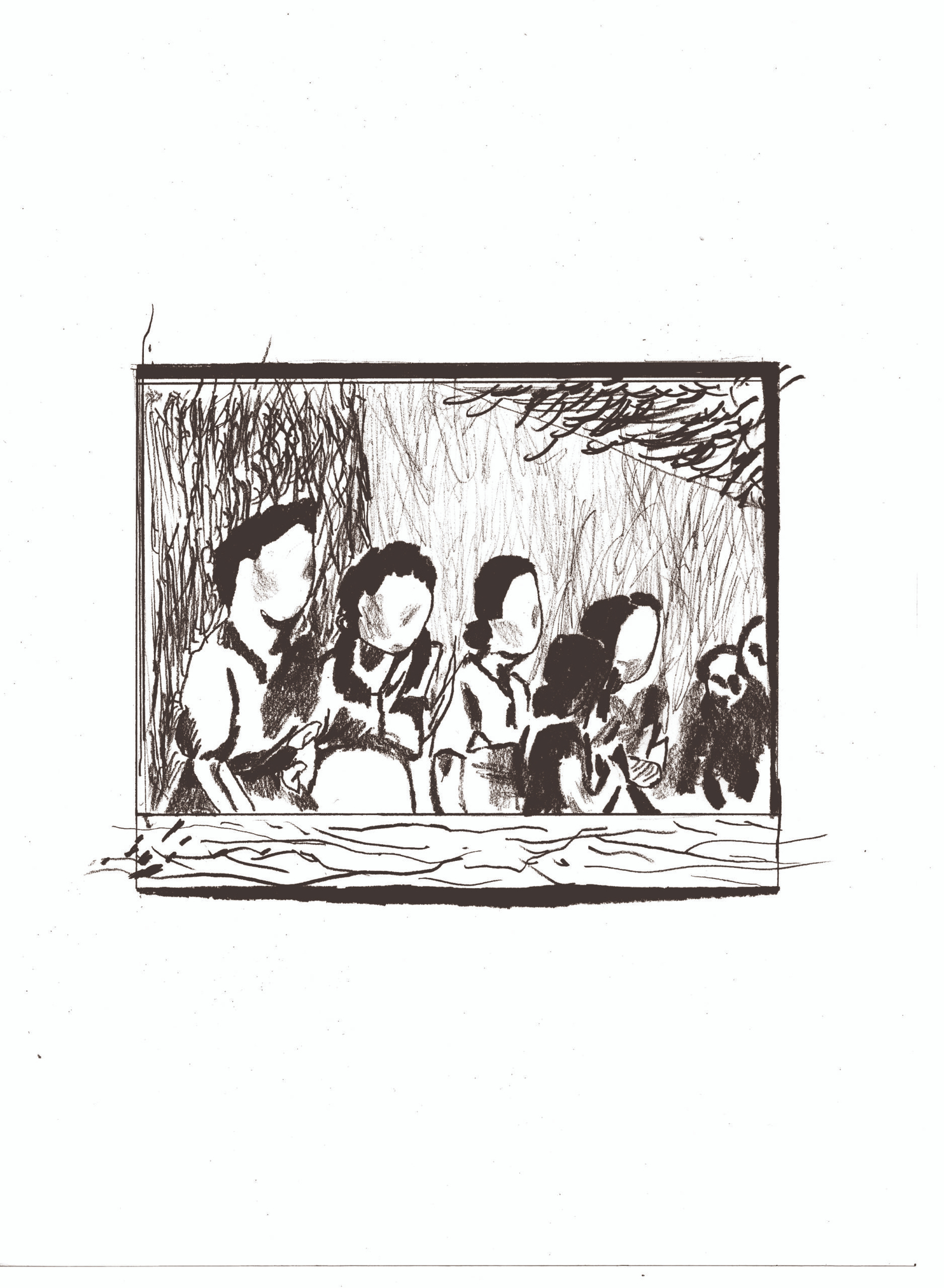

I wanted to almost erase every pre-educated imagery of Comfort Women in my mind. So naturally, in the process I wanted to capture the realistic element of the issue, based on journalistic documentation.

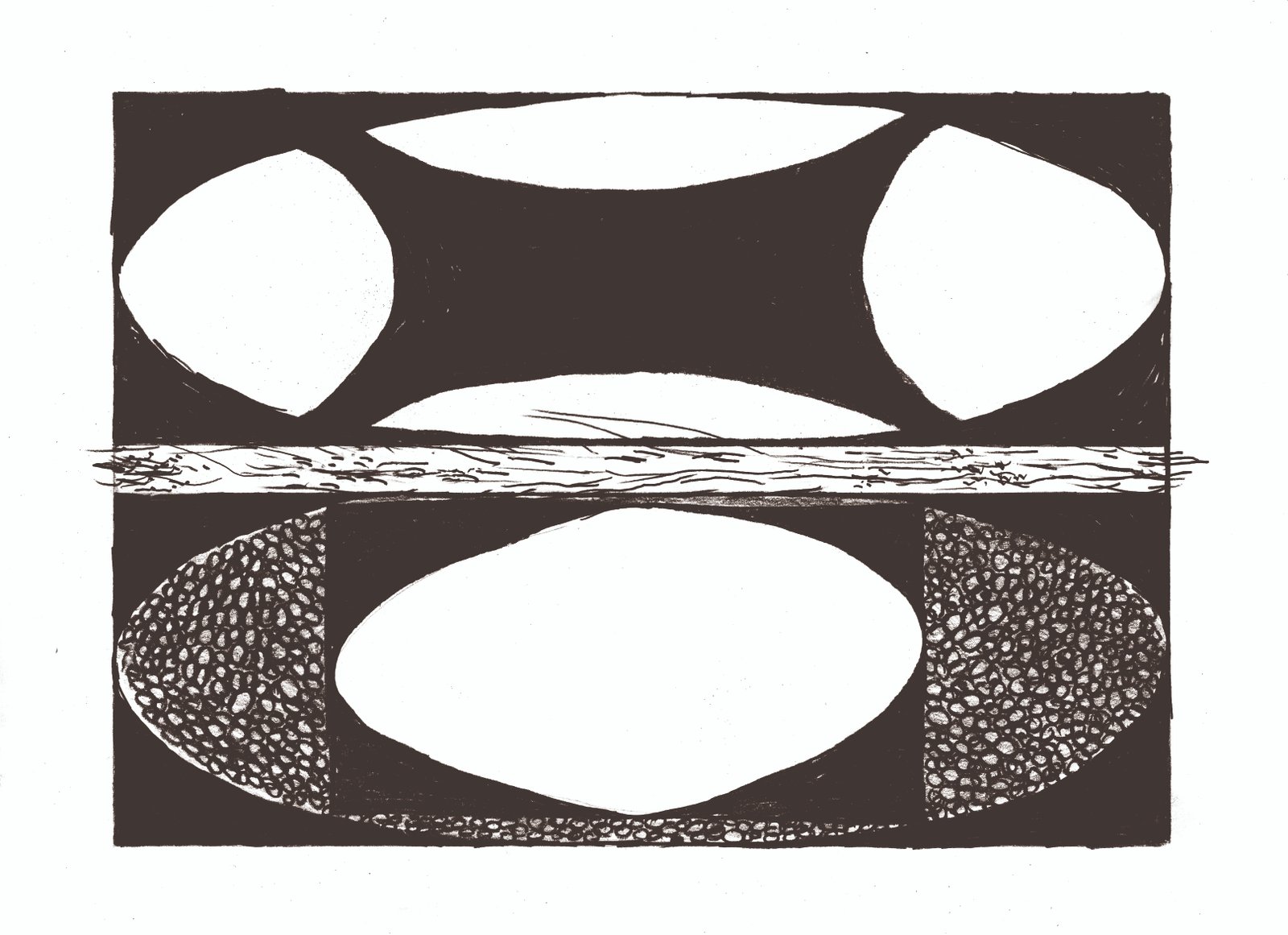

If the illustration works around any imagery that promotes stereotypical femininity, it would be insensitive belittlement of comfort women’s suffering and also the part that they are human before being women. And it was hard to contemplate outside of already formed political views of the comfort women issue considering how densely emotional the history of the colonial period is.

These are the transcription of the time that they had to seal down their emotion, their memory. These are the attempts to reflect the comfort women ‘s experience as it is.

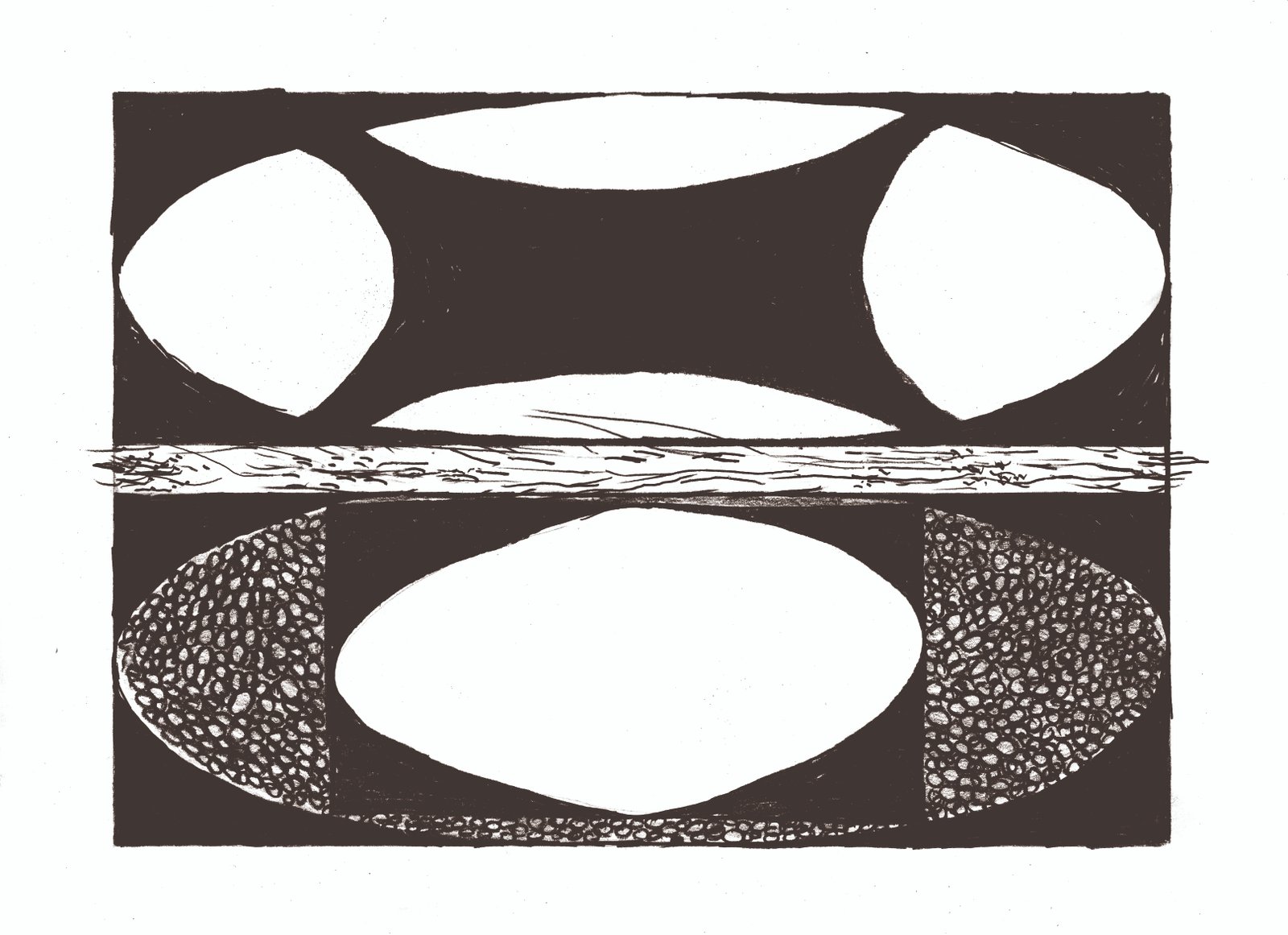

Certain frame that oppressed women in patriarchal society, isolated environment with deleted contact of outside world during the Comfort women period, and whether it is now or before, still confined emotions that cannot be adequately expressed.

Born and raised in Korea, Rondi Park is interested in how to transcribe “in between” social situations in visual way. Her research forms around journalistic details and information which she often uses to create different narratives. Her recent ongoing project “Cunning Raccon” explores the relationship between her and North Korea and how as a kid she had to be traumatized by South Korea’s propaganda.

To check out some of her other work,

instagram @rondinotrondy