Palestine, a holy land indeed, is filled with olive trees, beautifully terraced farmland, bright flora, and one of the largest bird migrations in the world, with one billion birds travelling through annually.

The first human farmers on Earth lived in Palestine in the Fertile Crescent, creating a tradition of subsistence and food sovereignty that has sustained communities across the globe for nearly twelve thousand years, and remains until the present day. Since the Zionist colonisation of the land of Palestine, however, this farming tradition has been under attack.

Agriculture as Palestinian Culture

More than 70% of Palestinians lived as subsistence farmers before Zionist colonisation which began in 1948. Thus, the land itself is integral to Palestinian culture and identity. Beyond this, though, the land is key to the everyday survival of the Palestinian people as, historically, the established food system was subsistence farming.

Through land occupation, colonial forces have simultaneously deprived farmers of not only their geographical identity, but their access to the human right to food, water, and the means to support themselves. However, steadfast Palestinian farmers are fighting to preserve their traditions.

Colonial extractivism and land rights as foundational human rights

An idea central to global colonisation is the extraction of natural resources for the benefit of the coloniser’s economy. This is at the expense of the colonised people’s labour, land, and natural resources.

This strategy is at play in Palestine as colonising forces are directly extracting value from Palestinian land. Israeli Zionist forces both systemically and on the ground are depriving Palestinians and their lands of the resources necessary to survive.

According to Article 1 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights as ratified by the UN General Assembly: “In no case may a people be deprived of its own means of subsistence.”

In Palestine, the land is the means of subsistence. Land rights include the right to naturally-occurring water sources and the right to food through your farm. Land rights also include the right to live on the land where your house stands and the right to occupy space in public without being criminalised.

By depriving local inhabitants of human rights, colonial forces systematically erase local economies and force the colonised into their own colonial-capital economy.

Through the process of colonisation, natural resources are explicitly restricted and then commodified, forcing local people to purchase necessities such as food, water, and housing from the occupying power. This, coupled with the fact that the right to work is also violated, leads to a culture of forced labour. With the threat of being starved, local residents are forced to enter an unsafe and largely unregulated job market to be able to afford the basic commodities that are their human rights, and were previously naturally-occurring and freely available.

Farmers movements for resistance and land sovereignty

As someone whose work focuses on neocolonialism and agricultural empowerment in the Middle East, I have experienced the immense and inspiring power of grassroots organisations fighting for food sovereignty.

Currently, I am part of Bethlehem University’s Palestine Institute for Biodiversity and Sustainability. This involves working with the Palestine Museum of Natural History, where I witness a living and breathing resistance to colonial occupation through curious, driven, and innovative urban farming, mutual respect and cohabitation with the environment.

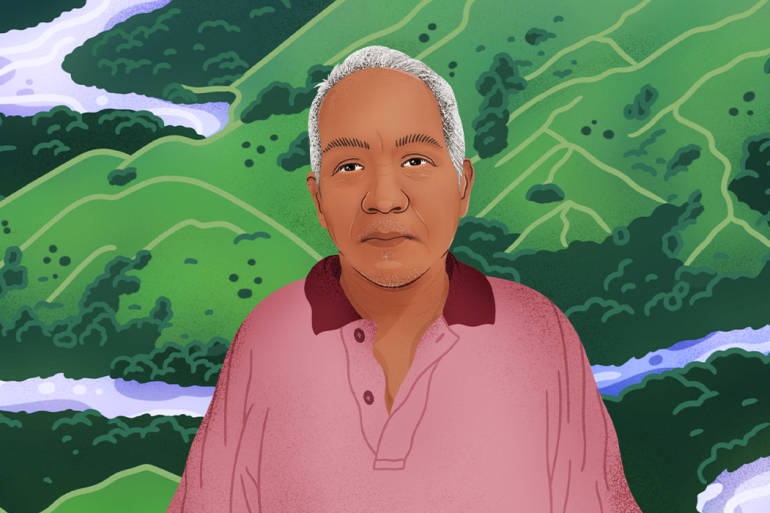

To learn more about the efforts of Palestinian farmers combatting occupation today, I spoke with Dr. Moayyad Bsharat, Director of the Lobbying and Advocacy Department of the Union of Agricultural Work Committees (UAWC).

UAWC is one of the largest agricultural unions in Palestine, bringing together Palestinian farmers on the ground to organise and cooperate against colonialism. Ultimately, UAWC aims “to support the steadfastness of the Palestinian farmer” by addressing and combatting occupation, extractivism, and climate change.

Naturally-occurring human rights

Before the colonisation of Palestine, water was not a scarce resource. Dr. Bsharat tells me: “Without occupation, we had plenty of water.” The Jordan River flowed through Palestine, providing drinking water and groundwater to sustain human, plant, and animal life throughout the region.

However, through colonisation, the state of Israel took control of all water resources, physically altering the landscape to reroute the Jordan River away from Palestinian farmers and towards commercial mass agriculture.

Since 1967, Palestinians have been denied the access to drill any new wells or to manage their own water systems, and access to naturally-occuring water sources is restricted to Israelis. In Gaza, water supplies are almost entirely contaminated and unsafe for drinking, while coastal access to water is shrinking due to oil drilling, pollution, and extraction. As Dr. Bsharat says: “Israel controls every drop of water, even that which comes from the rainfall.”

Further, mass commercial production and agriculture has systemic effects on the climate as a whole, altering the seasonal weather and leading to drought, desertification, floods, and otherwise irregular climate events.

Through restructuring the natural environment and monopolising water access, Israel affirmed its goal to increase profit and prioritise settlers’ rights at the expense of Palestinian residents and the environment.

Area C: Colonial Expansionism and Extractivism

Area C is the area of the West Bank which is recognised internationally and legally as Palestinian land, but administered militarily and governmentally by the State of Israel. This administration controls over 60% of the West Bank of the Occupied Palestinian Territories and contains the most fertile land in the occupied territories. This is the site of new settlements through colonial expansion, which is illegal under international law.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

Dr. Bsharat explains that Area C’s relationship with natural resources exemplifies the issue of land colonialism. Palestine is well endowed with groundwater from the natural aquifers, as the “collective of groundwater [within 1948 borders] is in Palestinian Territories, specifically Area C.”

Due to its groundwater, this land is heavily valuable agriculturally and for water access. Monopolising land access through de-developing Palestinian agricultural society is therefore central to controlling the water resources of the land and preventing self sovereignty.

In overusing water to support non-native or mass agriculture for economic or aesthetic value, Israel systemically deprives Palestinian agriculture and thus Palestinian human rights.

The stark juxtaposition of water use in Israel versus the Occupied Palestinian Territories is telling. Houses in the State of Israel are supplied with a cold and hot water dispenser which delivers an unlimited supply of fresh and filtered drinking water through the National Water Carrier, Mekorot. In the Occupied Palestinian Territories however, people who historically have had unrestricted access to water through natural resources are now forced to ration water due to the inconsistency of access from the state.

Erasure of Palestinian Agricultural Society

Driving through the State of Israel is enough to comprehend the blatant denial of Palestinian civilisation. Along the Israeli highways, you can see huge stone terraces as evidence of Palestinian agricultural society. These terraces were built as agricultural infrastructure, critical for farming on a mountainous terrain such as Palestine. On a drive across the country last month, I asked my (Israeli) driver about the reason for the stone terraced land; she simply responded that “it is natural.”

Along the drive, you can also see huge forests of densely planted trees. The Jewish National Fund, an organisation for the development of Israeli territory, funds the planting of forests largely directly atop remains of Palestinian civil society. In an effort to “make the desert bloom,” as Zionist colonial fantasy encourages, forests are planted explicitly on top of villages and communities to hide evidence of Palestinian life before their systemic expulsion. This is an ongoing colonial project and continues to fund the direct erasure of even the history of Palestinian culture and civilization.

In this, we must understand the importance of the tradition of farming; to erase Palestinian culture and specifically Palestinian agricultural history is to deny thousands of years of farming tradition.

Decolonisation on the ground: Unionising agriculture

Through the efforts of organisations such as UAWC and the Palestine Institute for Biodiversity and Sustainability, Palestinian farmers are organising to combat their human rights deprivation through a core facet of colonisation: land rights.

UAWC serves as a “base for local agricultural committees from cities, rural areas, and refugee camps in the West Bank and Gaza.” Currently, UAWC contains more than 120 agricultural committees in Palestine, each unit containing at least one-third women members.

UAWC works in “full coordination with the Palestinian Authority and specifically the Ministry of Agriculture,” instituting systems of governance to ensure human rights access. However, because the goal of UAWC is to ensure access to land and natural resources rights for Palestinians, this goal directly contradicts Israel’s colonisation project.

Thus, despite having no affiliation with political parties, UAWC has been deemed a politically dangerous terrorist organisation by Israel, leading to a decrease of international funding. UAWC is only one of the many NGOs and human rights organisations deemed as terrorist organisations by Israel; by categorising these organisations as such, Israel discourages foreign aid and stigmatises those working for human rights solutions on the ground.

International funding is a large source of stability for Palestinian NGOs as they are operating within an occupied state; thus, this disenfranchisement has had detrimental effects on the capacity of human rights organisations.

Dr. Bsharat tells me that the goal of defunding UAWC is colonial expansion: “No one will work in Area C, which gives the green light to the Israeli settlement government to increase settlement to Area C without any doubt and no one to stop them on the ground.”

UAWC also organises a national seed bank that preserves native Palestinian seeds, which are essential to maintaining a connection with the natural land of Palestine and essential to ensuring food sovereignty. Globally, UAWC is a member of La Via Campesina, the largest peasant movement in the world, coordinating efforts of farmers and peasants globally to advocate for their rights to food sovereignty, climate justice, and land rights.

A globalised resistance

In understanding the systemic human rights violations of the colonisation of Palestine, we cannot overlook the entire peoples who have also combatted destructive extractivism and domination, either colonially or neo-colonially, throughout the world.

In much of our neocolonial world in the present day, human rights continue to be violated through destruction and commercialisation of natural resources, forced labour from foreign corporations, and deprivation from land and food sovereignty.

Above all, we must come together to realise that the same systems of domination and destruction of colonialism are still at play today, creating a system of international trade and globalisation that systemically devalues labour and human rights in the so-called Global South. In a time of climate crisis, for the sake of not only humanity but the entire natural world, we cannot afford to allow oligarchs and corporations to destroy our home at the cost of so much of the world’s population and natural resources.

In supporting the steadfastness of Palestinian farmers, we support human rights to water, food, and subsistence. We support the right to culture and the right to self sovereignty. Thus, enacting the right to subsistence as ensured by Article 1, is an act of colonial resistance, combating the colonial, extractivist forces that attempt to deprive Palestinians of basic human rights and commodify and commercialise the natural resources of Palestine.

2022 sees the crippling combination of the climate crisis affecting all continents, a pandemic, economic and democratic collapse on the brink, and an increasing awareness of global power relations, climate injustice and oligarchy (even in the West). We can look to history to understand how these systems were established originally and cooperate towards viable solutions to this monopolisation of power. In the West, we must decolonise our own logic and narratives, reframing how we view global labour and reconsider that our commodity culture is at the direct cost of land, labour, and natural resources.

As the grand mural at the Israeli border wall two blocks from my home at the Palestine Institute for Ecology and Biodiversity reminds us, revolutions such as the invention of farming have begun here in this holy land before, and the right to Palestinian subsistance and soveriegnty will surely soon be restored.

What can you do?

- Read The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine by Ian Pappe

- Read The Persistence of the Palestinian Question: Essays on Zionism and the Palestinian Question by Joseph Massad

- Read Sharing the Land of Canaan by Mazin Qumsiyeh

- Find out more about Food Sovereignty HERE

- Read “Facing the Forests” by A. B. Yehoshua

- Watch: Palestine 1920: The Other Side of Palestinian Story by Al Jazeera

- Watch Walled Citizen by Sameer Qumsiyeh

- Support Union of Agricultural Work Committees

- Follow La Via Campesina

- Follow Palestine Institute for Biodiversity and Sustainability

- Support Palestine Natural History Museum