shado have teamed up with A Growing Culture on a series, themed Land Defenders. In this series we will be spotlighting the work of frontline groups around the world working to defend their land, water and human rights in the face of increased oppression and violence. In this first article we speak to Margarita Pineda, a land defender from Honduras

La Paz, a Department in southern Honduras, is a paradise where rivers and streams flow. Where the fertile soil produces coffee, bananas and chilis, the mountains hold minerals and precious metals and the trees breathe life.

But, for generations, it has been an epicentre of exploitation.

Honduras was initially a Spanish colony and later became a Banana Republic, where the American-owned United Fruit Company controlled Honduras’ lands, economy and government. Now the country has become a hub of neoliberal development policies, which intensified following the 2009 US-backed coup d’etat.

The country has endured unending foreign control of its lands, as well as the massive extraction of its natural resources. The Lenca Indigenous community that lives in the mountains of La Paz have borne witness to this violence and have organised themselves to defend their lives, territories and cultures before they are completely destroyed.

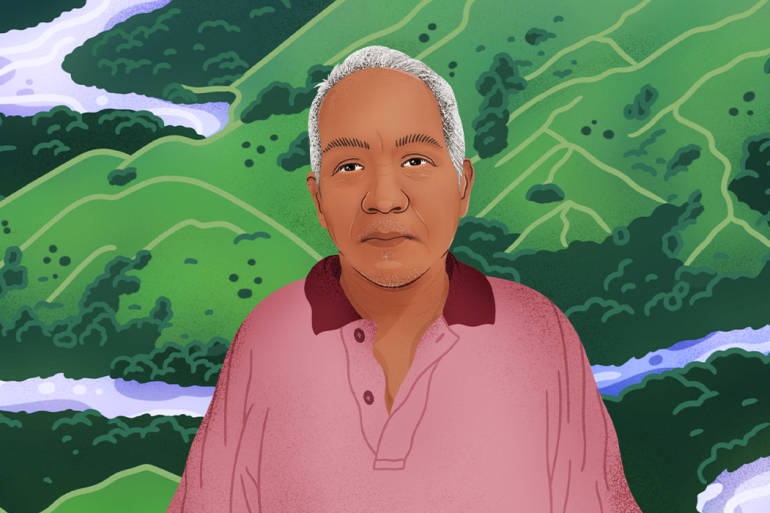

I spoke to Margarita Pineda, a fearless woman who forms a part of MILPAH, the Indigenous Lenca Movement in La Paz, to hear more about the situation on the ground.

Her voice is motherly; she calls me compita, little comrade, before going on to explain their struggle. “Our region has been handed over to transnational companies,” she says. “Just around our territory there are three hydroelectric dams, Aurora-1, Corral de Piedras and Sazagua, that, since 2009, have caused drought-related deaths in our communities.”

In the midst of the post-coup crisis and after the right-wing National Party of Honduras took power in 2010, the Honduran National Congress approved a General Water Law which allowed for the country’s water resources to be concessioned to third parties.

Around the same time, the government named much of Lenca territory as a “productive water zone” and Honduras’ government-owned National Electric Power Company began approving hydroelectric projects like Aurora-1.

Violations and Manipulation

“From before these projects even started operating, they were violating our Indigenous and human rights,” Margarita says. “Our communities were never consulted, which goes directly against our right under the UN Tribal and Indigenous Peoples Convention, ILO 169. They also manipulated our communities with fake promises.”

The community has waited in vain for schools and health centres to be built, reforestation programs to be set up, as well as increased access to potable drinking water and electricity, all promised by the people behind the Aurora-1 project. The reality has been very different.

“The water levels in our rivers and streams have lowered, which has resulted in some communities no longer having access to water,” explains Margarita. “They have also built many roads which have killed our flora and fauna.

“These people supposedly conducted an environmental study and received signatures from our community – but all of that was orchestrated by them in order for the project to go ahead. Nothing about this is sustainable or legal.”

A Global Witness investigation revealed a huge conflict of interest: that the director of both the Aurora dam and another dam in Lenca territory, Los Encinos, is the husband of Gladis Aurora López, the President of the ruling National Party, Vice-President of Congress, and one of the most powerful figures in Honduran politics.

The Danger of Defending

Violence has been inflicted not only upon the Indigenous communities’ territories, but also on land defenders themselves. On 27 March, Margarita was attacked by armed men.

“They threatened to kill me. Shots were fired at my house,” she says. “I know it’s because I am an obstacle for these big businesses. I don’t know where the next bullet will come from; it could be from a policeman, from a hitman, or even from one of my own people. They bribe our people, the ones that know where we eat, where we sleep, how we move. The threat is everywhere, but it is not going to stop us.”

In 2015 alone, five members of MILPAH were assassinated and many of their leaders have received death threats or have been attacked. On 15 May, another defender, Donaldo Rosales, was assassinated in Comayagua.

Honduras remains one of the world’s most dangerous countries for land defenders and environmental activists, with more than 140 defenders killed since 2009. Corruption and impunity are the norm and the killing of environmental defenders almost always goes unpunished.

Not only does the state often turn a blind eye to murder and human rights abuses; sometimes it even plays a role in orchestrating them.

A key example of this is the assassination of Berta Caceres, an Indigenous leader and co-founder of the Council of Popular and Indigenous Organisation of Honduras (COPINH), who was murdered just after winning the Goldman Environmental Prize for protesting against the Agua Zarca dam.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

This was an emblematic case in Honduras, showing that even with international recognition, land defenders can still be killed.

It also exposed just how many layers of corruption were involved; how U.S. special-trained elite military forces played a role, as well as the dam construction company, the government and organised crime syndicates.

Margarita remembers Berta and the important role she played. “I went to see Berta when they began these hydroelectric projects in our area. She told me that we needed to organise ourselves in our region. It was after this that we formed MILPAH. COPINH always supported our struggle.”

The Double Struggle: Patriarchy and Land Defence

MILPAH is now in 15 municipalities and has around 90 Indigenous councils. Margarita is the coordinator of women and gender within the organisation.

“As women, we have a double struggle,” she says. “We fight to defend our territories and our waters, but then within our organisation we have to fight against patriarchy and machismo. We have a right to be listened to as women. Sometimes I speak with strength and it scares the men. There have been times when they have threatened to kick me out of the organisation but I will not let anyone push me around. I left my husband, I have six children to care for but I am still here and still strong. I am a rebel by nature,” she continues, chuckling.

“During the pandemic, machismo really increased in the community. We were all locked up. There was a lot of violence, a lot of depression, and many people lost their jobs.”

It was in light of this that Margarita helped create the collective: Lenca Indigenous Women Referents of La Paz (MURILPAZ).

The collective is part of MILPAH but is made up of only women and now operates in 10 municipalities in La Paz. In Margarita’s area there are 15 MURILPAZ groups that are working to formally establish themselves. So far the women have built a maternity home, and are working on projects to strengthen their economic autonomy. They also have put in place cooperative agricultural projects to seed food sovereignty.

One of these cooperatives is a group of 18 women that are working to grow chilis, but they face various challenges including climate change and rising prices.

A Vicious Cycle: Poverty and Dependence

“The war between Russia and Ukraine is affecting us here. Before, we could buy fertiliser for US $25 but now it’s between $55 and $60. It is too much for us; it means that we lose money instead of make it. The problem is that groups like USAID came to our territories and promised to ‘eradicate poverty’ by bringing us seeds and fertiliser, but the seeds were genetically modified. They changed the memory of our earth and created more poverty and dependence.

“This is why we are trying to make our own organic fertiliser,” she explains. “We are working to heal the Earth so that we can cultivate our own foods. We want to break away from this dependence and return to working the land in a more healthy and ecological way.”

Aid, in Global South countries, has long been used as a tool to replicate colonial structures and increase dependence on Global North countries, rather than help communities build their autonomy.

It is a vicious cycle that keeps communities impoverished rather than increasing their capacity for self determination. Genetically modified seeds and fertiliser is one example of transnational companies taking over Indigenous and peasant ways of life, displacing local knowledge and cultures even further.

Margarita also mentions that the banks that gave communities predatory loans are now seizing their lands. Migration of young people is rising as poverty is increasing and opportunities are diminishing.

A Potential Hope?

Margarita explains that in spite of the challenges ahead, MILPAH will keep fighting on the ground. There might even be hope in the country’s newly elected left-wing President, Xiomara Castro.

Castro is currently taking away concessions from mining companies and development projects, as well as openly calling for investigations into the murders of various environmental defenders, including Berta Caceres.

Castro’s win was the biggest in Honduran history and was largely thanks to the votes of young people.

It is a blow to the power of the National Party and their neoliberal agenda, but there are still worries. “Castro is putting in a lot of legislation that is affecting big businesses,” Margarita says. “We are worried because we know foreign and national investors will not just sit and watch with their arms crossed.” There is also slight confusion as to why the U.S. is publicly supporting her presidency.

Margarita sighs, “all I can say is that as Lenca people I believe that we have the intelligence of our ancestors to see the reality and know what is best for our territories. We will keep defending what is ours, come what may.”

The story of Margarita Pineda and the Lenca community in La Paz is the story of communities across the continent. Foreign governments and corporations continue to seize Indigenous lands and persecute the communities working to defend them. As migrant caravans become more common we must remember that they are the product of unending exploitation that communities and their lands continue to face under imperialism.

What can you do?

- Follow: COPINH Honduras on Facebook

- Read the book Harsh Times by Mario Vargas Llosa

- Read the book Who Killed Berta Caceres by Nina Lakhani

- Watch the Documentary: Documental Margarita Murillo

- Watch the Documentary: Life and Debt

- Find out how Brazil is denying the basic human right to water

- Read how Indigenous land defenders in Ecuador and leading the fight against extraction

- Find out what the Biden administration means for Latin America and climate justice

Are you Honduran or Latinx?

- Get in touch with marinatricks222@gmail.com or +4407495787923 to build in line with these movements

Thumy says, “For Margarita’s portrait, I wanted to show her among a flowing stream and trees that breathe life, just like the land she’s defending.”