Mbonjo is a village located in the littoral region of Cameroon, about 40 kilometres away from Douala, the country’s economic capital and largest city. Like most villages in the area, the houses in Mbonjo are surrounded by thousands of oil palm and hevea trees: it’s in the heart of the country’s largest palm oil and rubber-producing region.

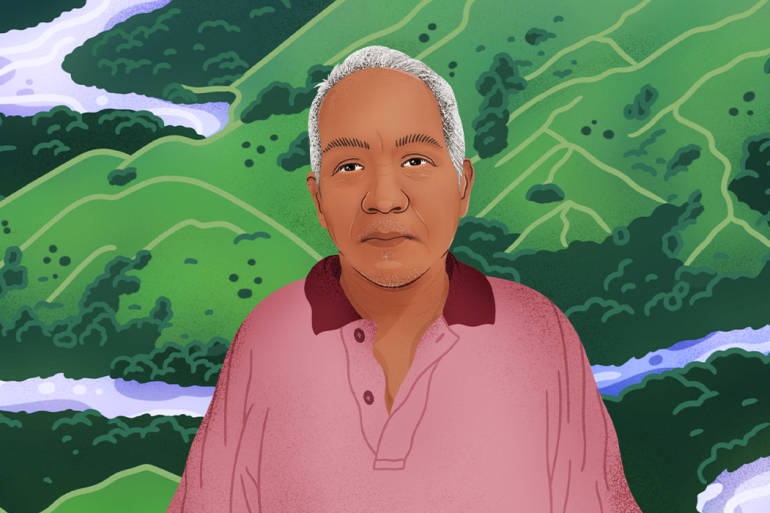

The company that owns most of the plantations is SOCAPALM (Société Camerounaise de Palmeraies). I had the opportunity to talk to one activist on the ground, who has dedicated his life to documenting the abuses of this neo-colonial agro-industry in the region, and to defending the rights of local communities.

How the area has changed

Emmanuel Elong was born and raised in Mbonjo. “People used to make a living from family farming, fishing in the river, and hunting and gathering in the forests,” he tells me during a phone conversation we had recently.

SOCAPALM was created in 1968 by the government of Cameroon and its plantations gradually expanded until they completely swallowed the village. “When I was little, my house was still bordered by a dense forest,” Emmanuel recalls. “The chimpanzees would come into the garden. But when the exploitation spread and they destroyed the forest, we saw how the animals would run away, jumping from tree to tree to escape.”

In addition to the terrible destruction caused by the expansion of industrial plantations, SOCAPALM ended up leaving the area’s inhabitants without land.

“The arrival of agro-industries has deprived us of arable land to continue hunting and gathering. What we have left today are the ‘lowlands’, which are wetlands that are considered unsuitable for palm cultivation,” he explains. As such, the lowlands are where they can carry out their traditional practices. “It is the only space left for our family culture, the only space we can use to feed our families.”

There are also issues with the river. “For fishing there are also problems because there are sand quarries, which prevent the population from practising traditional fishing.” And that’s not all; there’s also an issue of chemicals emitted from the SOCAPALM factory being discharged into the river. “It has become one of the most polluted rivers in the country,” sighs Emmanuel. “We can no longer have fish like we did before.”

Access to clean water has also become a huge problem, as Emmanuel tells me. In Cameroon – like in many countries in the Global South – most people are living without connection to a potable water network. “The only water we have access to is water from the rivers, but this water is polluted,” he explains. “This creates a threat to us and our health conditions.”

And alongside these problems, locals do not seem to receive any type of compensation. “We have no more land, we have no health centre, no school. Today, the children have to travel 5 kilometres to go to primary school! This company has been there on our land for years, and we don’t benefit from it at all,” Emmanuel laments.

Poor working conditions for plantation workers

Many villagers were forced to work in the industrial plantations to make a living, but suffer under poor working conditions. “The majority of employees work on renewable contracts, they are not permanent employees,” says Emmanuel. “They work without any protection. In case of an accident, the company does not cover health costs. Workers have no social protection either for themselves or for their families, they have no retirement plans. And the wages are too low.”

The company not only takes advantage of the lack of opportunities in the village, but also preys on vulnerable communities to recruit them to work in the plantations. “Many workers are from the north of the country and other coastal regions,” Emmanuel explains. “The majority are internally displaced people from regions that are in conflict, and who have had to flee their villages.”

Militarisation and increasing violence against women

During the past decades, SOCAPALM have been hiring security guards with the “official” mission to “protect the crops” from the villagers who’ve been accused of stealing the palm tree nuts.

But what the local population has actually witnessed is the multiplication of security groups who police and criminalise the village population. “The presence of soldiers in the village, who come into our homes and watch us – it’s as if we were at war!” Emmanuel complains.

This policing impacts the community in a big way. “SOCAPALM has also managed to divide us in the village, to pit us against each other,” Emmanuel continues. “The company employs young people from the village to monitor the other inhabitants, and encourages the village chiefs to agree to give subcontracts and to put down the other inhabitants.”

The impact of the militarisation is particularly dangerous for the women in the village.

“The inhabitants are abused, the women intimidated and assaulted, because now, to access the lowlands and be able to continue practising family farming, you have to cross the palm plantations. When the women cross the plantations, they are harassed by security guards,” Emmanuel tells me.

He specifies that this violence also happens within the plantations: local women that work for the SOCAPALM are often assaulted by the SOCAPALM’S employees. “The men who are team leaders in the plantations threaten the women not to pay them if they do not accept their advances,” he says.

According to GRAIN, a small international non-profit organisation that works to support small farmers and social movements, this situation is not only true in Mbonjo. A report published in 2019 reads: “when these industrial plantations encroach onto community land, sexual violence, rape and abuse against women and girls increase dramatically. This happens wherever industrial plantations are established and irrespective of whether the plantation crop is palm oil or rubber.”

What locals are experiencing in Mbonjo is a crystal clear reflection of the lies of “green” and “sustainable” capitalism. Companies are invading communities by force and making huge profits all around the world – and especially in the Global South – promising jobs, and so-called “development.” However, what local populations really get are a few crumbs of benefit, counteracted by a huge amount of violence and destruction.

Greenwashing

Despite all the atrocities that Mbonjo’s people have been facing, SOCAPALM claims to be producing “sustainable” palm oil and to be a “socially responsible” company. SOCAPALM was even certified by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO).

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

According to the RSPO’s criteria, this certification guarantees that the company operates in a way that respects and protects wildlife, the environment and local communities, treats workers fairly, and halts deforestation. After Emmanuel’s testimony, the certification of the SOCAPALM just sounds like a really bad joke.

“When we learned the principles of the RSPO, as human rights and community defenders, we thought that we had found the answers to many of our problems. In reality however, this certification only exists to launder companies. During the visits for certification, RSPO representatives only interviewed people who work for and support the SOCAPALM.”

Emmanuel continues: “They even arrived in SOCAPALM’s cars! SOCAPALM has all the officials in its pocket: the elected officials, the police and the military, the company manages all of them.”

The RSPO has been criticised by local communities and organisations around the world for failing to deliver on its promises, not only in Mbonjo. In a report called Burning Questions: Credibility of sustainable palm oil still illusive, the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) highlighted generalised fraudulent assessments by the RSPO, and documented that abusive labour practices, forest clearing, territorial conflicts, and even human trafficking had been permitted on plantations belonging to RSPO members.

This isn’t really surprising. The RSPO certification began in Switzerland in 2004 under the leadership of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and was funded by organisations like the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group, and multinational companies that buy palm oil, such as Cargill, Nestlé, Unilever, PepsiCo, and Procter & Gamble.

RSPO and its little green palm tree logo appear to be much more like a greenwashing operation than a real guarantee of any sort. Given that consumers all over the world – and particularly in the Global North – are getting more and more information about the negative impacts of palm oil production, industries and multinationals that depend on palm have developed marketing strategies to reassure their clients and continue selling their products – without making any significant changes.

The constant expansion of a colonial and capitalist market

The problem is that palm oil is known to be the most versatile oil in the world. It is used in the manufacture of so many household goods including food, cosmetics or candles. It provides the foaming agent in almost all shampoos, liquid soaps or detergents, raises the melting point of ice cream and is increasingly used as a cheap feedstock for agro-fuels suitable for cars, ships and planes, especially in the European Union. The palm kernel is also used as animal feed.

Furthermore, it is a highly productive crop that is capable of producing more oil with less land than any other existing vegetable oil: a palm oil plantation produces 10 times more oil than a soybean field and six times more than a rapeseed field, according to the French Alliance for Sustainable Palm Oil.

In Africa, and particularly in West Africa, it has been traditionally used for thousands of years. Before colonisation, palm trees were not cultivated in plantations, but were present at a low density in plots intended mainly for food production. The industrial cultivation of palm oil in plantations started with the colonisation of the continent by European countries. At the same time, other plantations were installed in South East Asia, particularly in Indonesia and Malaysia.

In Cameroon, in the aftermath of the Second World War, the regions of Edéa and Moungo had vast colonial plantations within veritable agro-industries intended for export. After Cameroon’s “independence” from French domination on 1st January 1960, most plantations started to be managed by the State, but were privatised again under the influence of the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), as part of so-called “structural adjustment programs” at the end of the 20th century.

“The former white settlers used these international institutions to come back and make huge profits while forcing Africa back into poverty. It’s nothing more than neocolonialism,” Emmanuel tells me.

Over the last five decades, the world’s production of palm oil has steadily increased. According to research published by The Guardian, between 1995 and 2015, annual production quadrupled, from 15.2 million to 62.6 million tons, and the plantations which produce it represent 10% of global farmland. By the year 2050, its production is expected to quadruple again, reaching 240 million tons.

The actual expansion of industrial palm oil plantations in Africa has all the characteristics of a new colonial occupation: lands are taken without consent and frequently with the use of violence, destroying communities’ ways of living as well as the local biodiversity, polluting the waters, and exploiting locals as workers in undignified working conditions.

According to information from the organisation GRAIN, only five companies control three quarters of the planted area of industrial oil palm plantations on the continent. Two of them, SOCFIN and SIAT, are former European colonial agribusiness companies.

And it turns out that, since 2000, the SOCAPALM that operates in Mbonjo is nothing more than one of the many local subsidiaries owned by the SOCFIN group. In fact, the nationally owned company was privatised and sold to SOCFIN, an agri-food multinational now controlled by the Belgian Fabri family (50.2% of the shares) and the French Bolloré group (39% of the shares). Today, the company owns some 58,000 hectares of oil palm and rubber plantations in the region.

Resistance

Fortunately, palm oil industrial plantations are facing resistance. Communities all over the continent are organising to defend their rights.

Emmanuel is an important part of this movement. When, in 2012, SOCAPALM announced that it would expand its plantations to Mbonjo’s wetlands, threatening the villagers’ access to cultivable land, Emmanuel decided to contact Vincent Bolloré – France’s most influential businessman, CEO of the French multinational Bolloré, a key shareholder of SOCFIN, owner of SOCAPALM – to complain about the situation.

A year later, in April 2013, together with hundreds of villagers living in and around the plantations, Emmanuel gathered to protest at the SOCAPALM factory and blocked the company’s heavy equipment and the entrance to the plant. Then, through the recently created Synaparcam, a local NGO dedicated to defending communities’ rights against industrial plantations, they started to build alliances with other residents living near Bolloré Group’s plantations in Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Cambodia. In 2015, they launched a global campaign against land grabbing. They have been active on an international level since then, sharing experiences with other affected communities in Africa and Asia, and defending their rights.

On a local level, Emmanuel and the Synaparcam continue to work tirelessly. “We coordinate on a national level through branches in different villages. This makes it easy to identify irregularities at the local level and report them to the company. If we don’t get an answer, we denounce it in the media, on social networks… Thanks to this, for the moment we have succeeded in preventing the company from accessing the lowlands”, he tells me.

Another huge activity has been to denounce and raise awareness about the terrible effects of the chemicals that are used in the plantations, as well as defending the traditional seeds and techniques.“Industrial plantations use large quantities of chemicals in their seeds and locals have started to buy them. “We raised public awareness about the health implications of these products and reiterated the importance of using traditional agriculture.”

In the industrial plantations, the palm trees that are cultivated are mainly modified trees that produce a bad quality oil. ”Here we have spontaneous palms – they grow by themselves. We use the whole plant for everything, from medicine to construction materials, to alcohol. Here in Cameroon and everywhere in Africa, the palm tree is an essential plant.”

Fighting against agro-industrial plantations is not only a struggle against destruction, but also a struggle for life: defending lands, forests, biodiversity as well as food sovereignty, culture, identity and traditional knowledge that communities have inherited from their ancestors.

Spread the word

When I asked Emmanuel what can be done to support his struggle and the global resistance of the hundreds of communities that are directly affected by industrial plantations, he had one clear and quick answer: don’t trust the small green palm tree logo and spread the word so real change happens.

“If our fight is beginning to be known today it is thanks to the journalists of international media who have been talking about us, the communities who live where these multinationals are established. Advocate for the communities, mainly against the banks that finance these companies, their customers and their suppliers so that things change. Here in Africa, the Bolloré group is so powerful that it managed to buy all the media that try to talk about it. Locally, there is no information, but at the international level it is possible, and we must talk about it and put pressure on the industry!”

What can you do?

To know more about Synaparcam’s actions in Cameroon and give some support you can visit this website.

To learn more about palm oil industry and communities’ resistance:

- Read this report on sexual violence in and around industrial rubber and palm oil plantations

- Check this call for international solidarity with women that live around the plantations You can have a look at this report to get more information on the lies about “sustainable” palm oil

- You can read about resistance in Africa with the report from GRAIN: “Communities In Africa Fight Back Against The Land Grab For Palm Oil”

- Finally, you can have a look at this investigation of palm oil plantations in South Mexico, to have a quick look at the palm’s expansion in Latin America

- Read more articles in shado’s Land defender series HERE

The Cameroon woman is feeling unsafe as she is being monitored by security guards, who assault women for crossing plantations.”