The Rio Ucayali is a winding river that forms a part of the Amazon river basin. Its curves snake-like through the heart of the Peruvian Amazon where it is a lifeline – both for the vibrant ecosystem that grows from it and for the Shipibo-Konibo and Xetebo Indigenous communities that live along its edges. But the riches, depth and inaccessibility of the Ucayali region have made it a central point of exploitation, corruption and criminal groups.

Aerial footage has begun to show how deforestation is accelerating in this part of the Amazon – one of the reasons being the invasion of the region by narco trafficking groups that are levelling the forest in order to set up clandestine coca farms. In 2021, according to the Regional Forestry and Wildlife Management (GERFFS), 31,500 hectares of the forest were cut down as a result of the expansion of narcotrafficking in the region.

One member of the community, who wishes to stay anonymous, explains that there are now at least 50 landing strips in the region that narco groups are using to export the coca.

“Not only do they grow coca in the region, but these criminal groups also process it to make cocaine. It brings a lot of danger to the region. In Pucallpa [a city on the River Ucayali] many people – Indigenous peoples and Mestizo peoples – have been assassinated,” he shares.

Stories of threats, bribes, land invasions and recruitment are becoming more common which has forced communities to defend themselves.

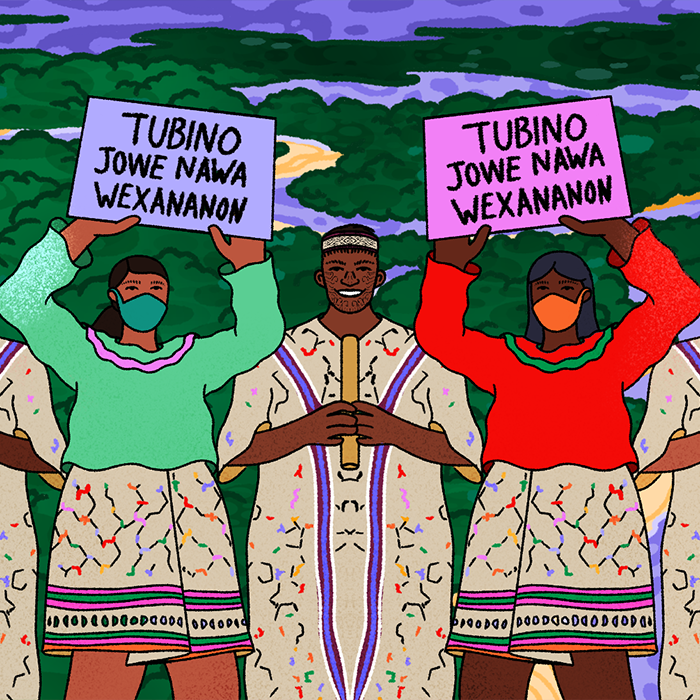

The Shipibo Konibo Xetebo Council (COSHIKOX), a council made up of 176 of the communities that line the river, have been denouncing the entry of these criminal groups for years – but in a familiar story, they have been met with authorities’ silence and inaction.

“The government is scared to intervene. The authorities say that the region is too inaccessible and that confronting these groups will result in too many casualties. This is why we’ve been obliged to organise ourselves,” shares a member of the COSHIKOX.

The COSHIKOX has now established its own Guardia Indigena (Indigenous guard) to confront the situation and defend their territories.

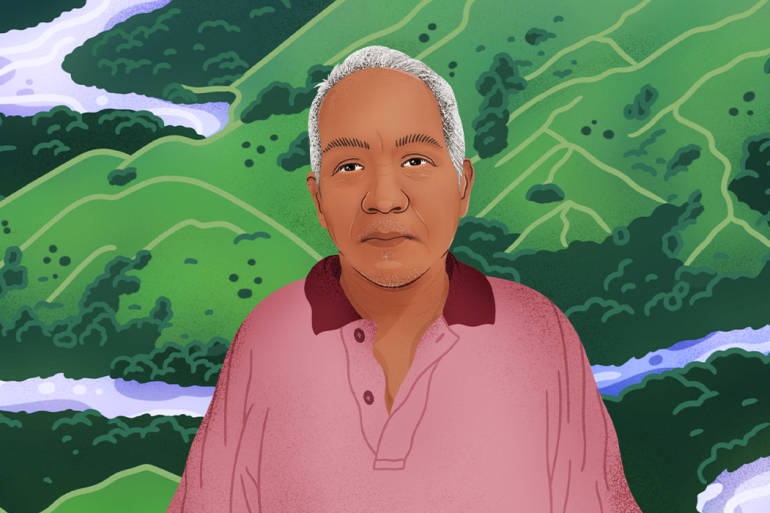

But they know that this comes at a huge risk. Since establishing the Guardia, multiple members of the community have received death threats from narco groups. The current President of the COSHIKOX, the Apo Koshi, Ronald Suarez, was once stopped in the night by a man on a motorbike. The man told him that they were watching him; that they knew where he lived, and how many children he had, threatening to kill him if he didn’t step away from leadership. Suarez didn’t bow to this pressure.

The illegal activities that occur in the forest are not limited to drug trafficking groups. The COSHIKOX also has to confront illegal logging, hunting and fishing that all seem to be part of an interlinked umbrella of organised crime operations.

Earlier this year, local Indigenous expert Bruno Pereira and Guardian journalist Dom Philips were disappeared and killed in the Brazilian Amazon for investigating the interlinking of fishing, logging and drug trafficking rings. And while international attention was rightly given to these murders, the continued assassination of Indigenous leaders receive little to no coverage – and so they continue to fall victim to these dangerous webs. This pattern seems to follow each curve of the river that spans along the heart of the continent.

Threats from religious groups

But it is not only criminal groups that are invading their territories.

Blond haired, blue eyed, straw-hatted Germans have also begun to deforest and take over the land around the Ucayali River. The Mennonites are an ultra-conservative Christian group closely related to the Amish, who believe that God is commanding them to live from the land as a result of Adam and Eve being cast from the Garden of Eden. However, many of them have decided to take up this ‘commandment’ not on their own soil, but by invading the lands of communities on the other side of the world. Flows of Mennonites have been migrating to Abya Yala (so-called Latin America) for the last 100 years.

The Mennonites have begun logging large stretches of Peruvian Amazon land and settling there. A report by the Monitoring the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP) estimates that deforestation linked to Mennonites has reached 4,800 hectares – that’s four fifths the size of Manhattan in New York.

Peruvian officials, lawyers and organisations like COSHIKOX are denouncing this invasion. Across the continent, there are currently over 200 Mennonite settlements – and so they have well-founded fears that there is more intensive deforestation and so-called ‘God-sanctioned’ invasions on the horizon.

Colonialism in action

Aside from the Mennonites and criminal gangs, the Shipibo-Konibo and Xetebo communities face another much more stealthy and violent invader: the western economic development model.

This model can be seen in the regional government’s concessioning of parts of their lands to companies under the guise of regional economic development. New “development” projects have threatened communities’ traditions, spiritualities, knowledges, ecosystems and ways of life, commercialising their peoplehood and cosmovisions – all while also making big money through intensive mono-crop palm oil farming.

The COSHIKOX reports how mono-crops are destroying the biodiverse polyculture of the Amazon, creating an ecological imbalance in the forest. As a result, livelihoods of local communities are diminishing, wildlife is being driven away, and diseases like dengue fever are spreading like never before.

The Amazon — the “world’s lungs”, and home to many Indigenous communities – is nearing a tipping point at which all life within it will rapidly decline.

Commodification of Indigenous traditions

The Shipibo-Konibo and Xetebo peoples are known for their intricate knowledge of ancestral medicine. During the pandemic they began to use a fruit called Genipa, traditionally used for hair dye, to also cure respiratory diseases. In order to safeguard it in their communities, they tried to patent it, but they found that it had already been patented by researchers who did not refer to the Shipibo Konibo communities at all.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

It’s not the only example of their Indigenous knowledge and traditions being commercialised by foreign companies. The patterns of their traditional artwork, Kené, which has ancestrally been used by the communities to communicate and teach their cosmovisions has, on various occasions, been taken by fashion companies and commercialised without the consultation of the community.

Majed, an adviser and member of the COSHIKOX, shares: “The authorities think that the Amazon territory and our cultures are only useful for their money-making capacity. We see development differently. That’s not to say that we do not extract from the land, but where we do, there is a relationship of respect and interdependence. It must be that the river, the trees, the wildlife, can all coexist in the same space, so that in ten years time, or in the next generations,we are all still here.

They say that we are not developed because we do not look like the city, but we don’t want to look like the city. Western development privileges companies, individuals and death. Development in our eyes is different, it is more long term and is not driven by monetary benefits, but rather the benefits to life that it can give the collective and that is inherently tied into our cosmovision and traditions.”

Autonomous governance

It is because of all these threats to their lives, livelihoods, and culture, that the Shipibo-Konibo and Xetebo communities are in the process of building up their own self-governance structure in the region, an Autogobierno.

An Autogobierno would institutionalise the process and right to self-determination, as this self-government would have the authority to determine what is best for communities in terms of implementing their own contextualised versions of development towards the construction of autonomy and a just peace in their territories. Annually they hold an Ani Tsinkiti, an assembly that brings together community leaders from across the territory. The assembly is a participatory decision-making process that is integral to the Autogobierno.

Essential to this process is the strengthening of the economic, socio-cultural and political bases within their communities.

“Whilst we are talking about building autonomy, we can’t still be dependent on outside structures,” says Ronald Suarez, the president of the COSHIKOX.

For this reason they are building up their own economic structures like the KoshiCoop, a cooperative where the community sells its produce like fruits, plantain, and cassava. They also produce their own products like ‘Bio-Camu’, a natural drink with important health benefits made from the Amazonian fruit camu camu. The cooperative supports the sustainable management of the natural resources of the territories, and gives market access at a fair price to the cooperative’s associated producers without the intervention of third parties – which have historically taken advantage of the needs of the community.

They have also built up their own communications services like a community radio and TV network that they use to strengthen their Indigenous cultural identity, deliver updates on the development of the self-government, give rights-based and political education and to organise the community in times of crisis, like during COVID-19.

A seat at the table

Alongside this, the COSHIKOX are strategically building relationships with people in the Peruvian government and are advocating for the participation of Indigenous people in decision-making processes. They support Pedro Castillo’s government for institutionalising the Indigenous Guard, which they say will help bring peace to their territories but also express strongly that they know only small concessions can come from working with the government and true change will take communities building their own institutions, self-determination and self-governing mechanisms.

Until then, these processes require defending and popularising. In October 2022, the Planet Repairs Action Learning Educational Revolution (PRALER) held a Glocal Week of Liberating Education at the SOAS, University of London linked in with communities in Afrika, Asia and Abya Yala. PRALER is a process to practically engage in, and defend, processes of self-determination and sovereignty being waged glocally. Majed from the COSHIKOX participated, giving concrete direction on how we can interlink communities’ processes of defence to provide security and strengthen our collective organisation towards self-determination. The institution-building processes that are taking place along the deep curves of the Amazon river are hidden but are creeping into light.

They are examples of fundamental principles that we must hold true. Our people have the power, ancestral knowledges and wisdom to free themselves and build up their own nations and institutions in a way that is best suited to meet their needs as a people interconnected with the needs of all life in their territories.

What can you do?

- Watch: A lecture from our uncle Majed from COSHIKOX held during the PRALER week

- Check out COSHIKOX’s website

- Watch the documentary When Two Worlds Collide