An aperture that neither

Offers me a shelter or retreat

And failing that, acknowledge

What at best just dulls the atrophy

‘A Sacred Bore’, Kapil Seshasayee

These lyrics by Scottish-Indian musician Kapil Seshasayee allude to the caste system and “atrophied” lives of individuals impacted by it. Casteism is a hereditary oppressive social hierarchy which places emphasis on ‘purity’: people from higher castes are considered ‘purer’ and granted the most privilege. The lower castes – the lowest of which, Dalits, or “untouchables” – are deprived of opportunities, resources, and often, basic human rights.

Detailed in ancient Hindu texts and practices in various manners across societies in the Indian subcontinent, the caste system as it exists today was cemented and institutionalised in India during British colonial rule. As a result of its prevalence in different South Asian religions, it seeps its way via migration throughout the world. Its insidiousness is amplified by the fact it is routinely and fiercely denied, especially in diaspora communities.

This lack of admission in the UK exists in spite of several government-commissioned and independent reports as well as surveys conducted by Dalit activist groups showing the contrary. This is potentially because some diasporic communities have never had to face it, or they wish to defend their reputation against accusations of ‘negative’ or ‘backward’ socio-religious practices. Leaders of some Hindu groups in the UK, such as the National Council of Hindu Temples and the Hindu Council UK, have in the past stated that efforts to pass anti-casteism legislation are ‘Hinduphobic’, claiming that casteism is not connected to the religion itself. Responding the UK government’s (now abandoned) move to introduce anti-caste legislation under the 2010 Equalities Act, the foreword to a report by the Hindu Council UK (HCUK) stated that: “the HCUK is not aware of caste discrimination here in the UK.”

Yet a recent example of the prevalence of caste structures in the UK – or at least recognition of their existence – happened during the appointment of its new Prime Minister. What is Rishi Sunak’s caste? was one of the most frequent Google searches made in India following Sunak’s promotion to the Prime Ministerial role in October 2022, betraying the persisting influence of the caste system in the South Asian diaspora and its social structures.

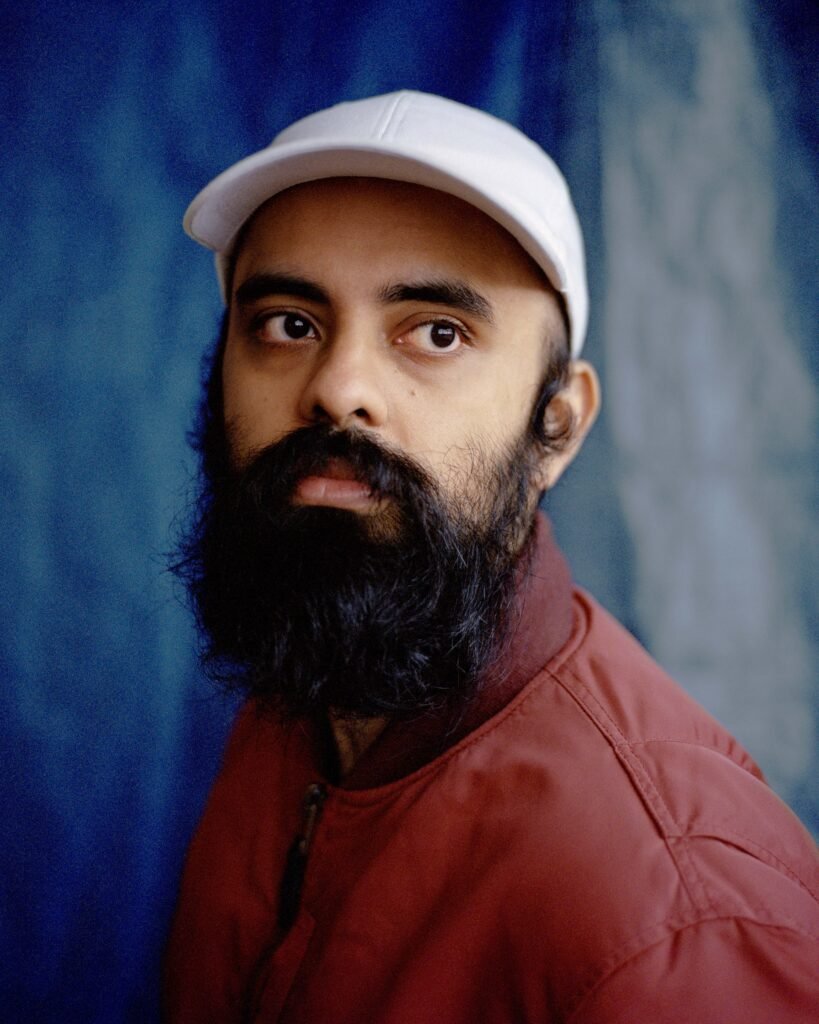

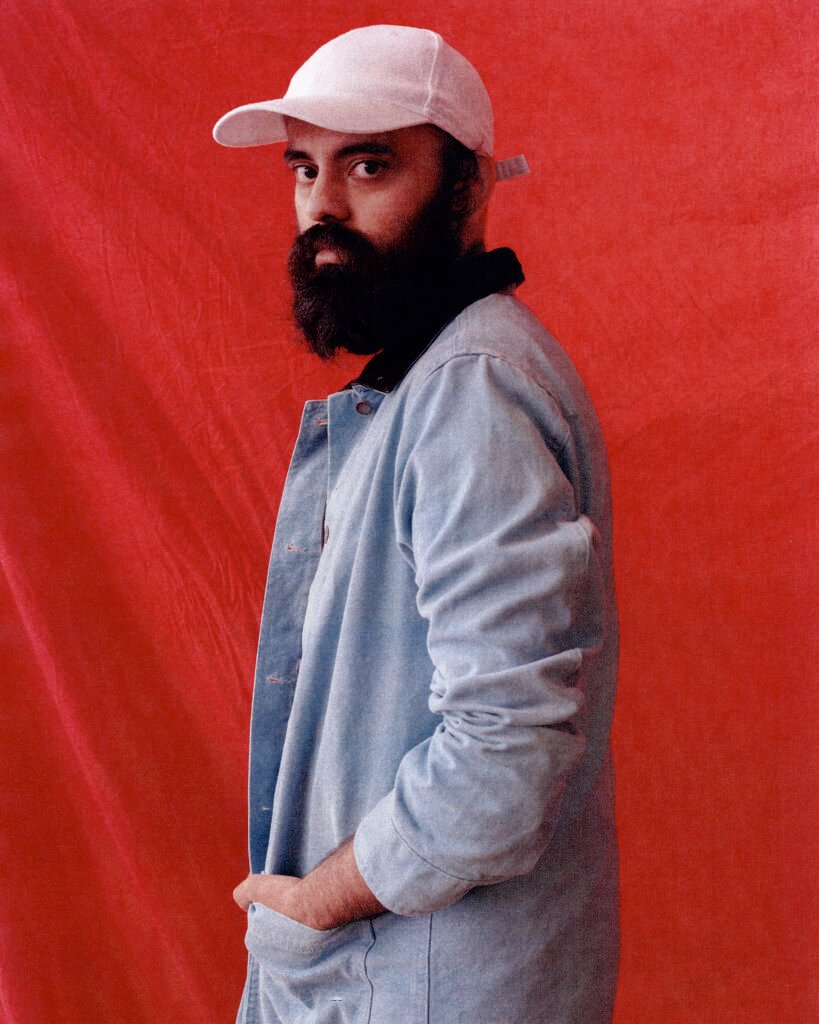

Unperturbed by the denial of caste discrimination, Kapil uses his songs as spaces to confront the oppressive system. I spoke to Kapil over Zoom the day before his newest album, Laal, was set to be released. On call, Kapil’s hands gesticulate beyond the limits of my laptop screen, letting slip his eagerness to talk about his work.

When I ask him what his experience has been trying to sing about largely unacknowledged issues like casteism, Kapil reminds me that, while people don’t necessarily talk about it, everyone has a story. “If you go up to anyone and ask them, as a South Asian or Indian, have you ever seen someone be casteist? Or, have you ever had a cousin in your family who just wasn’t around anymore because their family didn’t like who they fell in love with? Everyone’s got an example, but no one wants to talk about it because it will paint them in a harsh light,” he says. Kapil felt compelled to communicate those stories. “Storytelling is a massive part of what I do,” he tells me. “I think that if I wasn’t doing that then the music wouldn’t achieve the same goals.”

For Kapil, music is the best way to platform conversations on issues like casteism and rising nationalism in India and its diaspora. Evident from the provocative beats and riffs in his songs, Kapil sees music as transcending entertainment: “Music serves a function – not only to get people dancing, but also to get them engaged with a new topic.”

Kapil describes his music as “desi-futurism,” which investigates what it means to be South Asian and looks at, he tells me, “what elements of our own culture can we improve upon from the inside out.” His fascination with the future traces back centuries; he has often thought about people’s disparate projections of the future. Through the lens of desi-futurism, Kapil is able to map his own idea of a more inclusive and dynamic future. His conception of futurism is also heavily influenced by Dr BR Ambedkar, who is known as the father of the Indian constitution and was a trailblazer in fighting for Dalit rights.

According to Kapil, Ambedkar thought about the future in a pragmatic but defiant manner: “A lot of people thought the caste system would be stomped out by now, but Ambedkar was very aware that it would take a lot longer than that, and that it may be a long time still, beyond our lifetimes, before anything gets done,” he says. Kapil’s style of song writing also attempts to strike this balance between forward-thinking and discontent with the present state. His is the work of a storyteller: tying in the past and present into artwork for future generations.

Kapil’s latest album Laal looks at how these discriminatory practices in India seep into the entertainment industry; namely Bollywood. The billion-rupee Indian film industry has found itself mired in controversies, like the use of incendiary stereotypes that fuel communalism and further nationalist propaganda peddled by the Indian government.

The first song in the album, ‘Gharial’, is about Bollywood films like Tanhaji unnecessarily stoking tensions between Hindus and Muslims in an already volatile environment, especially in historical retellings where Muslim characters are often shown as invaders and threats. By telling the stories of minority communities instead, Kapil attempts to subordinate the capitalist chokehold of industries like Bollywood which he believes is “trying to stir up profit and controversy sales.”

We also talk about ‘Rupture of the Wheel,’ arguably my favourite song on the album. Musically ingenious, Kapil tells me that the song’s lyrics are rooted in an unfortunate reality of a man in a wheelchair who was assaulted because he did not stand up for the national anthem. For Kapil, this song and its lyrics are “a visceral image of a lack of seriousness taken when it comes to disability rights in India, and how we can see this reflected in the UK also. The cause is close to his heart, too; he explains: “As someone who has taken care of disabled parents for many years, I wanted my beliefs to come out in my work.”

‘Rupture of the Wheel’ is as complex in its composition as it is in its concept: an Indian classical intro entices listeners, before leading into an explosive hyperpop-avante rock song with an Urdu rap making up the bridge. Just as I’m admiring the evocative title of the song and its chorus, I am reminded of the harsh reality that underpins this artistry: Not a fast tide or custodial / Or a pass time ever parochial / Independently I bide my time / Culminating in the rupture I designed. Dealing with various themes including disability rights, nationalism and corruption, the song serves as a powerful indictment of both Bollywood and the right-wing Modi government’s role in fostering an environment of intolerance, designing its own rupture. The Urdu rap in the song is by the Pakistani Daranti group, and debuts non-English lyrics in Kapil’s music. “I love it,” declares Kapil, admiring the lead rapper Hassan’s punk style. “He’s almost yelling in the way he goes about it, with so much urgency to his flow.” Connecting the violent forces of hyper-nationalism to government propaganda, the rap begins: ‘Azaab ya barbariyat? / Fasaad hai wataniyat’ (Torment or jingoism? / Nationalism is a troublemaker).

Kapil is sceptical about ideas of nationalism, both at home in the UK and in India, where the clarion call of patriotism masks regular instances of caste discrimination and racism. “I think nationalism pretends to be inclusive a lot of the time,” he muses. “There’s a prevailing message that If you’re proud of your country then you can stay – but that’s not true, is it? Not when people who can’t stand for the national anthem are literally assaulted or certain minority groups forever remain ostracised.”

What I admire most during our interview is Kapil’s subtle, yet often urgent, ability to weave between issues across borders which are affecting marginalised communities in both the UK and India. He deconstructs stereotypical attitudes towards countries in the Global South and uses his affinity for storytelling to jump from one continent to another, literally and sonically, telling me about his adventures on tour in Canada, US, and Germany while localising his lyrics and influences in India, Scotland and the UK.

Kapil’s music speaks out against powerful institutions in both India and the UK, and because his reach is global, he’s often been warned against talking about these ‘sensitive’ topics. However, he believes having difficult conversations is the only way to question and challenge what it means to be South Asian: “You have to have difficult conversations if you want to do that, and you sometimes have to keep having those conversations, even if no one else is listening to you and people are angry about what you’re saying.”

“I demand the autonomy to make art about what I want to make art about,” he continues. With an emphasis on nuance and authenticity, he believes that there is hope to fight against divisive and capitalist-driven rhetoric in India and the diaspora. Hisnew album brings a new wave of support, and thought it, Kapil is hopeful for the future of his own music, and the awareness it brings: “It’s nice to think that you can be authentically angry about something and have people rally behind you.”

What can you do?

Follow anti-casteism activists doing invaluable work in the UK:

- Equality Labs

- Dalit Diva

- دلت کیمرہ (@DalitCamera)

- The Dalit Voice (@ambedkariteIND)

- DALIT WOMEN FIGHT! (@dalitwomenfight)

Watch:

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

Read:

- Annihilation of Caste by BR Ambedkar

- The Gypsy Goddess, by Meena Kandasamy

- This news report on caste discrimination in Australia

- Music when words fail – the resurgence of protest music in India – Shado Magazine

Check out: