My conversation with Finn O’Brien came about because he’s had enough of people making assumptions about him.

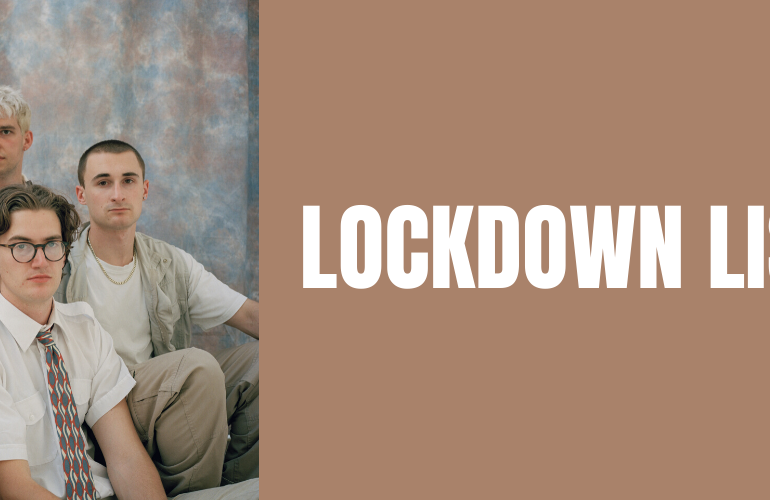

He’s the frontman of It Man, a band previously known as The Jacques, and they’ve just released their first single in two years: White Heat. It’s an indie-punk summer track that makes you feel like you’re reclining on a deckchair cracking open a tinny, and it immediately went onto my hot boy summer playlist.

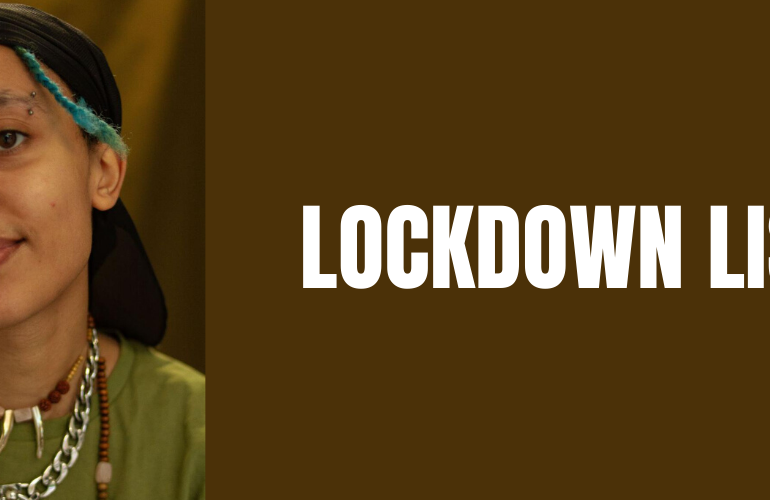

In a meeting about promoting the new song, someone asked Finn if he was worried that his music was “too blokey,” whether it was appropriately “with the times” – the implication being that it was too masculine to be seen as progressive, perhaps because of the swaggering, drawling vocals from Finn himself. He responded by informing them that he was, in fact, a transgender man – someone who had lived experience of misogyny and had to fight hard to own his masculinity.

I am obsessed with this story, and I wish that someone had been there to film the jaw-drop moment for posterity. I think most trans people have that experience at least once if they are regularly assumed to be cisgender. I could picture the expression of shock, the face someone makes when their entire perception of gender is challenged the way only trans people can challenge it. I can’t help but grin when Finn recounts the tale to me, though he is very polite about the whole thing.

“I can understand where the conversation came from, because the music industry is almost all cisgender men, and there’s a lot of talk about getting balance on festival bills and stuff,” he says, “which is very important – but I am in this bubble of being assumed to be just another cis bloke when I’m not.” I wonder, is this why he decided to go public?

“Everyone has different reasons for coming out or not, but for me it feels like a coming of age thing.” He explains that when he was younger, he was terrified of people knowing he was trans, but as he’s gotten older and more comfortable in himself, he doesn’t care as much.

“I’m not ashamed, and I think [speaking out] would be a good thing to do,” he tells me, explaining that in years gone by he’s been able to ignore a lot of problems in the music industry and the trans community, and he doesn’t want to do that anymore – especially given the escalating culture war that’s unfolded in recent years.

There was a golden period after Laverne Cox’s 2014 “transgender tipping point” and before 2018, when the gender critical movement started to gain momentum during the Gender Recognition Act reform debate – a period where both Finn and I were living as transgender men.

Life wasn’t exactly easy, but it felt like there was less pressure on trans people. People were starting to become aware of us, but there wasn’t really any organised effort to turn people against us the way there is now. I can understand why being open feels more important for Finn now than it did when he started performing with The Jacques in 2014.

“I’m one of the lucky ones, but I have friends who are trans women, or non binary, or haven’t transitioned medically, and their lives are so much harder, and getting worse, actually. That scares me,” Finn says, explaining a sense of guilt for “sailing along in [his] male privilege.”

I think it’s an easy trap for trans men, especially white trans men, to fall into, and I tell him so. Because transitioning is such a slow process, you gradually become accustomed to male privilege in a way that makes you think you’ve earned people’s respect because of hard work, tenacity, or any number of positive qualities that trans people typically possess. “I thought I’d passed some initiation,” Finn agrees, “but they didn’t see me as an equal before, and they only do now because I look like them, basically. It’s not quite right.”

While I’m listening to Finn talk about how drastic the differences were between how he was treated as someone assumed a woman to someone assumed a man, I think about how much the experiences of trans people have to offer feminist thinking.

Here is a whole host of people who can talk, at length, with detail, about the difference in attitudes towards men and women and gender non-conforming people – and many feminists seem more interested in debating whether we even exist.

Finn himself says he considers himself a “quieter” trans person, not necessarily keen on getting involved in trans-related activism, but there’s no doubt that he has insights into the music industry that could be transformative if reckoned with – not only for trans people, but for cisgender women as well.

Finn’s days of not talking about his experiences are over, and he wants to be part of the solution to the “macho” culture in the music industry: “I’ve been able to ignore the problem – now I’m treated in such a way that allows me to, I want to be more aware of it.” I hope that the industry is ready to grapple with what Finn has to say now that he has made clear that he isn’t another cisgender heterosexual man who is out of touch with the realities of misogyny.

Indeed, knowing that Finn is trans, I see a new dimension to his music. The latest single, White Heat, and the mostly black and white video that goes alongside it show a trans person carving out space for themselves in nostalgia, in music, in masculine aesthetics. We see clips of Finn dressed in a suit and singing to the camera interspersed with flashes of working-class people going about their business in the 50s and 60s – men waving fond goodbyes to their wives on the way to work, smoking cigarettes, and lingering looks at huge banquets of retro party food.

That context changes the entire project from “four blokes in a band” to something quite subversive. Trans men are very rarely considered in the public imagination due to the heavy dominance of transmisogyny in British culture – indeed, I cannot name you a trans man in the public eye in the UK off the top of my head. It is exciting to see a trans man flourishing and given space to express his gender this way without feeling pressured to make it a gimmick.

Although Finn hasn’t written specifically about being trans, he does think that being trans has had a positive effect on his artistic practise: “it’s made me more sensitive and thoughtful,” he says, “I wondered for years what it would be like after I transitioned, and that escapist world has stuck with me, for better or worse. That informs the lyrics the most.”

I can see exactly what he means: people often half-jokingly say to me that I am like a man in a book written by a woman – my experiences of navigating the world read as a woman reverberate in my behaviour and the work I produce, whether I’m directly addressing my transness or not.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

Transness is a gift to this world, and Finn is a shining example of the rich cultural perspectives that trans people can offer – how our experiences can foster creativity, outside-the-box thinking, and wisdom.

What can you do?

See It Man Live in June 2023:

- 8th June / Newcastle / Cluny 1 w/ BRIX SMITH

- 15th June / Stroud / Subscription Rooms w/ BRIX SMITH

- 16th June / Portsmouth / Wedgewood Rooms w/ BRIX SMITH

- 18th June / London / AMP w/ MENADES

- 19th June / Brighton / Prince Albert w/ MENADES

Read more about trans men’s insights into sexism and misogyny:

- Transgender Men See Sexism From Both Sides

- As A Trans Man I’ve Seen Sexism From Both Sides in the Workplace

Read more about trans people in music: