The recent global newscycle has seen police violence spotlighted once again. The death toll of protestors rises in Colombia. Palestinians continue to suffer at the hands of Israeli police. Czech police are under scrutiny over the death of a Romany man following restraint. More generally, heavy-handed law enforcement has formed a core pillar of what has been a securitised pandemic response.

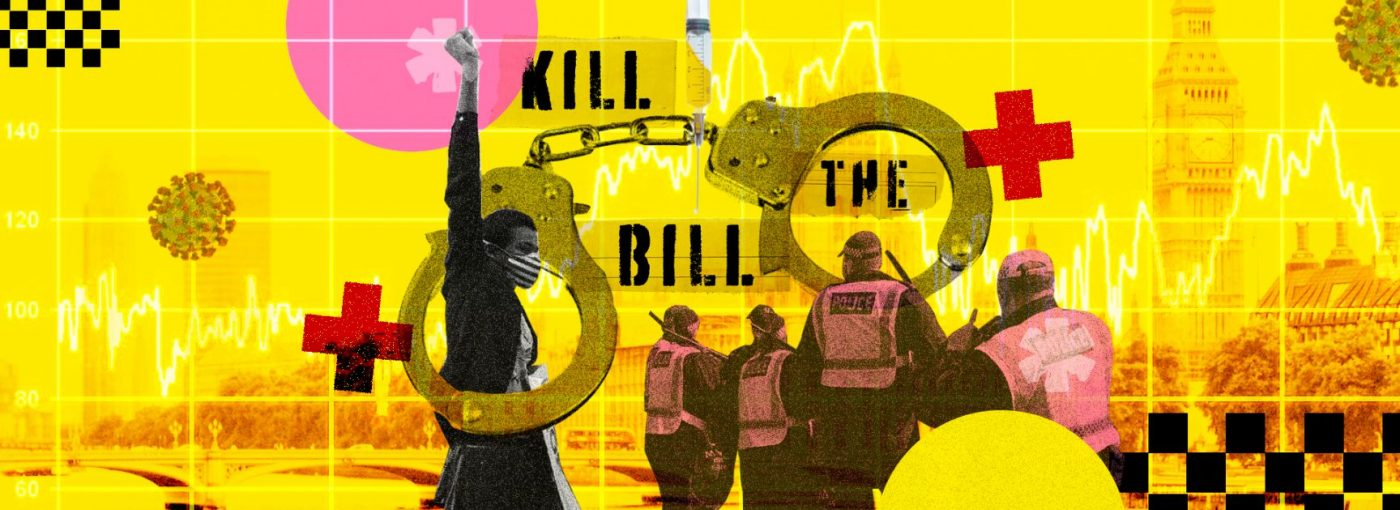

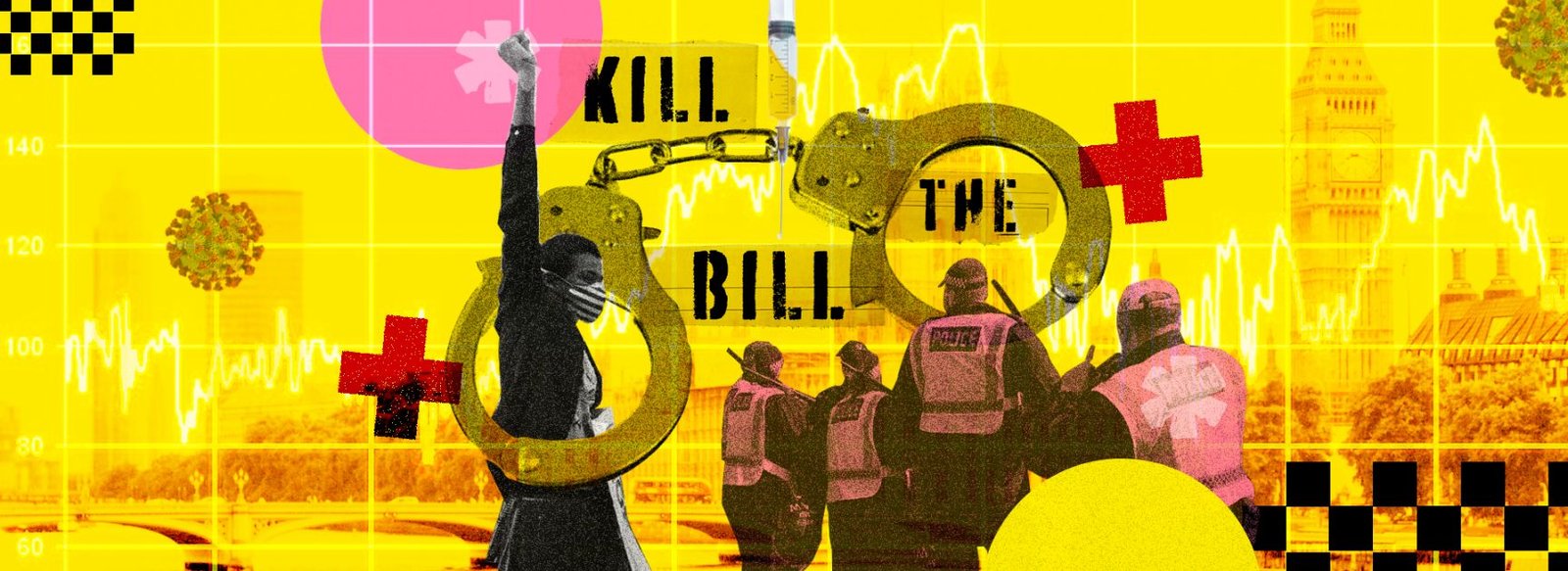

Closer to home, the Policing, Crime, Sentencing, and Courts (PCSC) Bill is now going through the House of Lords, due for its second reading. We have seen the emergence of a huge social movement against the bill, most notably led by grassroots groups such as Sisters Uncut. In particular, the bill’s threats against the right to protest has made it a nexus for solidarity across causes.

However, this is only one part of a wide-reaching bill, over 300 pages long, that sanctions more pervasive police presence and powers into all walks of life. As a healthcare professional, there are several reasons I think this bill will be harmful to people’s health.

First, policing itself is harmful to public health – and this bill’s strengthening of police powers will only lead to even worse outcomes for people from already over-policed and criminalised communities. It is no coincidence that those most criminalised and those with the worst health outcomes are one and the same – the most minoritised. The root causes of poor health – poverty, poor housing, education and employment, underwritten by successive austerity budgets – are the very same ones associated with crime, as highlighted in Institute of Health Equity’s ‘The Marmot Review 10 years on’.

And, the bill specifically introduces so-called ‘Serious Violence Partnerships’, which poses a duty on public service workers including health workers to hand over information on patients to the police, threatening patient confidentiality. This proposal typifies one of the ways in which policing harms public health, especially for marginalised communities, through the imposition of surveillance that blocks access to healthcare and widens criminalisation.

Impact of Serious Violence Partnerships (SVPs)

Serious Violence Partnerships (SVPs), proposed in the PCSC bill, impose a statutory duty on specific health bodies such as Clinical Commissioning Groups and Welsh Health Boards to disclose relevant data to police and other bodies.

They build on the legacy of the ‘multi-agency approach’ in Blair’s ‘tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime’ law and order platform, including Safer School Partnerships (SSP), which introduced the idea that public services needed to work with the police to reduce violent crime, but which, as the Institute of Race Relations shows, led to increased criminalisation and exclusion of Black working-class youth from the school system.

Confidentiality of medical information is the basis of a patient’s trust in a healthcare practitioner. On more than one occasion, I’ve looked after a patient escorted into the Emergency Department under police custody in handcuffs, and asked officers to step away during my interaction with the patient. Despite the remonstrations I have heard from officers that they cannot allow this or that they require information from the assessment, healthcare professionals are duty bound to respect confidentiality of patients, unless it is absolutely felt that not doing so “may expose others to a risk of death or serious harm”. Respecting confidentiality in these cases has enabled me to provide care that centred the needs of the patient, disproportionately often vulnerable and from a minoritised background.

SVPs severely undermine this patient trust. The PCSC Bill proposes wide-ranging powers for the Secretary of State to authorise disclosure of information at far lower thresholds than health professionals currently would. It would mandate information sharing into police databases without mechanisms to challenge requests, even going as far as criminalising health professionals who do not comply.

The progressive infiltration of law enforcement into the healthcare and public health space is deeply disturbing, but is not new, and the disproportionate harm to marginalised communities is well-documented. Medact have written about the damaging and racist Prevent duty, particularly in mental health care, whilst Docs Not Cops have reported the devastating impact of Hostile Environment within the NHS. Health professionals are not trained as de facto agents of law enforcement as part of their job – nor do we want to be. The mandated identification of ‘at-risk’ individuals according to ‘risk factors’ identified by the Serious Violence Strategy – local deprivation, truancy, low self-esteem – is likely to flag a racialised and materially-deprived population as ‘at-risk’. The potential result is increased surveillance of minoritised populations, the expansion of intelligence databases and more racial profiling.

Yet, we do not only oppose the duties listed in the Serious Violence Partnerships. We opposed the bill in its entirety.

Policing is a threat to public health

The police force is an instrument of state control. Structural violence is not an unfortunate side-effect of policing, but its core modus operandi. It perpetuates a cycle of community harm by criminalising the conditions it reproduces to target minoritised people, those with mental health conditions, of no-fixed-abode, or facing drug and alcohol addiction. Prosecutions are disproportionately for low-level charges, such as drug possession.

Moreover, racism is endemic in policing and the prison system in the UK, despite the claims of the Sewell report. Amnesty found that 72% of those on Metropolitan Police Service Gangs Violence Matrix – a database of suspected gang members in London – were Black, despite the police’s own figures which claim that 27% of those responsible for serious youth violence are Black. Black people were nine times more likely to be stopped and searched compared to white counterparts, rising to 18 times more likely to be stopped with no reasonable suspicion (‘under a section 60’). Black individuals were more likely to face direct police violence: in a mental health context they were four times more likely to be sectioned, detained against their will, and twice as likely to be arrested under the 136 police provision. The schools to prison pipeline tells a similar story. The treatment of the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller community, explicitly targeted by the ‘unauthorised encampments’ clauses of the PCSC bill, must also come under scrutiny.

For these reasons, policing itself is a threat to public health.

As Guppi Bola, ex-interim director of Medact, puts forward, public health involves “…the development of the social machinery to insure everyone a standard of living adequate for maintenance of health, so organising these benefits as to enable every citizen to realise their birth right of health and longevity.” Policing and the carceral state are not compatible with this description. Instead, we must look towards more transformative forms of justice that foster safety and centre community-driven models of care. We argue that stripping back police powers, and reallocating funding to community services that target the core political, social and economic determinants of poor health and crime would constitute a truly public health approach to violence.

The PCSC bill is a public health concern because it allocates more power to policing and the wider prison system, which we know are fundamental determinants of poor health. We stress that a public health approach to policing is nothing other than abolition. The bill is incompatible with the principles of freedom, compassion and collective wellbeing of communities, all of which are important tenets of public health. Thus, we call for it to be terminated with immediate effect.

More about Race & Health

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

Race & Health is a multidisciplinary collective of academics, artists, activists, policy makers and grassroots organisations. Our goal is the reduce the adverse effects of racism and discrimination on health. Race & Health have previously written in an academic journal on the intersection between police abolition and health, the problematic nature of racial categories, and held an event exploring related themes titled ‘Defund Dismantle Decolonise’. We have a quarterly newsletter that can be accessed here.