Khashayar “Khash” Khabushani’s debut novel I Will Greet the Sun Again is an intricate Persian rug. Woven in the traditional storytelling style and language of his roots, ancestry, and homeland, Khash infuses his novel with all the life, identity, and truth of growing up as a queer Iranian-American in America.

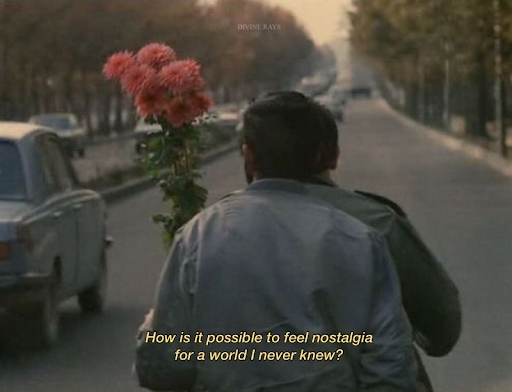

Khash teases the tension between the desire to become All-American as an immigrant and the cultural amnesia of growing up in a country that demonises your homeland. A coming-of-age tale of identity, assimilation, and America, I Will Greet the Sun Again drenches the reader in the budding excitement of the discovery of one’s queerness, surely evoking nostalgia for those who have experienced such.

Khash’s life parallels mine; we are both Iranian-American queer people who grew up between the late 90s and early 2000s in America. While he grew up in California, I grew up in Oklahoma, both of us learning to balance our familial Iranian and assimilated American identities.

Khash’s storytelling is one immediately familiar to me as an Iranian. It’s a tradition that I have known since birth; one that winds emotions, humour, drama, and lengthy asides of explanation, scene, and setting. When we spoke, Khash and I reflected on how we use art and culture to feel at home and in touch with our roots even away from home.

The Iranian diaspora is one of endless personal histories. The circumstances surrounding many of us are fraught with judgement, shame, or xenophobia in the face of Islamophobia due to extreme anti-Middle Eastern sentiment which the US government modelled for its citizens in the aftermath of 9/11.

Khash explains that for many Iranian migrants, “the goal quickly becomes to be unseen and to disappear in this American landscape because of racism and prejudice.” He reflects on his own family as I reflect on mine: “There was so much emphasis on erasure of our own Iranianness.”

Khash’s work is political without speaking about politics. “All art is political, of course,” he tells me. Khash tells me that his politically-artistic style is inspired by the Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami who “made political statements, but in a sort of roundabout way… the way he made his political statements was by showing Iranian life and letting the camera roll, whether it was in Northern Iran or in the city.”

In the novel, Khash embodies the same desire to portray Iranian life realistically with its beauty as well as its flaws, “to show Iran and to show Iranian-American life by letting the camera roll, in a sense.”

“Otherness” and Assimilation in America

Khash and I speak about how we came to understand our Iranian identities in the context of the late 90s and early 2000s. In Oklahoma, I didn’t have Persian peers or community members; I was simply identified as “other.” I knew that I wasn’t the same, but I didn’t know exactly what was different. Thus, I found my identity through being “other” and with the rest of the “other” kids.

Khash tells me about how he came to know his identity growing up, similarly finding his own identity through his community including immigrants, whether or not they themselves were Iranian. “I really wanted to contribute something that would reflect back the experiences that people in my life growing up had,” he says. “I couldn’t stop thinking about the friends and community members that gave me so much love; my peers, some of the older kids living in the apartment complex with me… who although might not be Iranian, whether we found each other because of poverty, or parental abuse, or having a single mom, I really also wrote the book for them.” Within these minoritised spaces, communities can find sameness in their “otherness.”

Diasporic identity finds itself in the “other” spaces of America and often deepens with one’s curiosity about their diasporic homeland and existence outside of the European gaze. Khash and I relate about how we explore identity through these “other” spaces and how “as a young person, you’re just borrowing and trying on different identities.”

Khash explains: “Especially when you’re young, whether it’s music or basketball or crushing on girls or boys, you’re aware of your differences, of course, but when something like 9/11 or ICE detention camps come up, you have no choice to be made aware even as a young person of your identity.”

Creating diasporic identity

In a study on transnational Iranian identity, Cameron Mcauliffe describes the Iranian diaspora communities who left due to the Iranian Revolution in 1979 as inhabiting “a state of exile from contemporary theocratic Iran.”

In his infamous book on assimilation and identity in a colonial world, Black Skin, White Masks, Frantz Fanon describes how assimilation unfolds in the West: “He becomes whiter as he renounces his blackness, his jungle.” Whether it was our language, physical appearance, or placing an American flag in our front yards, the American identity required renouncing any ties to one’s homeland.

While for many of our parents and grandparents, the goal was to disappear outside of their roots, Khash explains that “then over time, for the first generation Americans, the goal is to be seen for their roots.”

He elaborates that this paradox “puts the next generation in a very interesting position because on one hand, they just follow suit like K does… and yet over time, especially when they get to see [their home country] for themselves, they are like ‘Oh, this is actually super dope, I love where my parents come from, and I can see these things in me too.’ Integrating that can be fraught and can take a long time to find one “sweet spot” of who they are and who they wanna be.”

As Khash, Fanon, I, and the rest of the New Americana explore our identities outside of the assimilation we learned in our lives, we together come to realise Fanon’s words:

All this whiteness that burns me… I sit down at the fire and I become aware of my uniform. I had not seen it. It is indeed ugly. I stop there, for who can tell me what beauty is?

Unseen spaces: countering patriarchy in Iran

In the novel, the protagonist K longs to inhabit the unseen spaces where his Mother and Aunt can express themselves without judgement, shame, or the wrenching grip of patriarchy. Similarly, Khash and I reflect on the unseen spaces that inspired him to write this novel.

Khash explains that “even admitting to yourself any kind of element of queerness felt so dangerous… and it didn’t even exist within the realm of possibility. Honestly, I think a lot of it is rage that I didn’t have the chance to do it as a younger person.” In these spaces of patriarchal and homophonic violence, even speaking these stories aloud and living one’s truth is a grave risk.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

Despite the patriarchal violence of the contemporary Iranian state, matriarchy and women’s power is a dominant and misunderstood part of Persian culture. Khash’s book reflects this dynamic gorgeously, each woman in the story carving out a dense character of justice, ethics, and the power of the unseen space. Khash tells me that while Maman and Khaleh (mother’s sister) “don’t take up much space in the book,” he considers those spaces as “some of the most important parts of the book.”

Khash reflects on his mother’s perspective of her son’s liberation and empowerment as an Iranian who proudly espouses his queer identity; Maman thinks, “I would have been killed or harassed or violated, and yet here is my child, seeking the very things that I tried to disappear within.”

Women are the doers, the powerhouses, the protectors, and the guardians of Iran, as evidenced clearly by the unwavering power of the Iranian Women’s Revolution almost a year after the killing of Mahsa Jina Amini. Since the killing of Mahsa Jina Amini in September of 2022 by the Iranian “morality police,” Iranians have taken to the streets with courage, empowerment, and rage against the patriarchal and oppressive state which uses violence against women, queer people, their allies, and those expressing distrust in the Regime.

Khash’s mother represents the power of Iranian women and their unbreakable sense of justice. Khash told me that after the publishing of this novel, his mother “couldn’t be more proud that this book is out…I think that gets to her, recognising that we are allowed to have Iranianness in America.”

Khash’s decision to publish I Will Greet the Sun Again makes a promise to readers that we of minoritised identities can heal together through vulnerable reflection of assimilation, power, patriarchy, and state violence.

Breaking the American Dream: The new Americana

Khash and I spoke about the power of our generation, now, and our unwavering commitment to our identity even if we didn’t grow up physically in our home country.

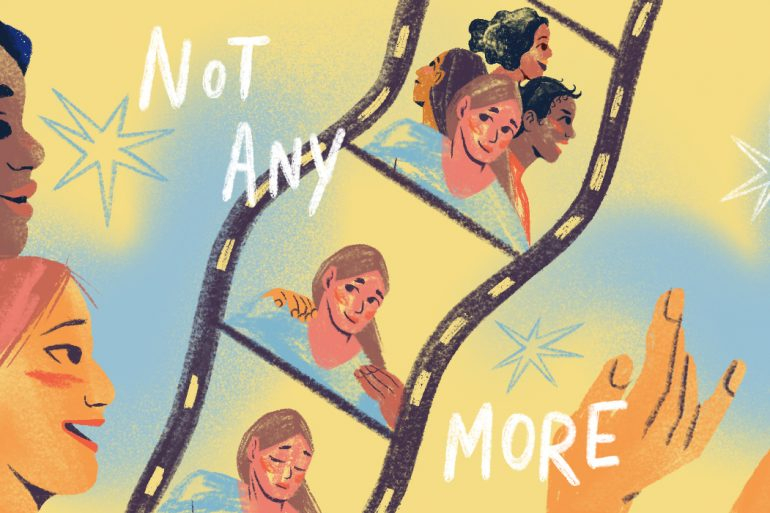

We spoke about the rising artistic genre of the contemporary diaspora including Ocean Vaughn’s works and how “in contemporary literature, there are voices… Chinese-American or Mexican-American or African-American, writing about contemporary America while also including those parts of their identities.”

This “New Americana” genre is being invented by the best of America and for the most important reason. Momo Boyd’s “American Love Song” captures the New Americana moment with curiosity of identity and nostalgia for a homeland, asking what it truly means to be American today. Her music is part of the collection “Music for the Revolution” which reinvigorates revolution with the joy of liberation, empowerment, and cooperation, reminding activists and advocates that liberation is a joyous occasion.

Today, the whole of us immigrant-American young people can come together to create a new identity of pride and strength in our diversity, bringing together the authenticity of our own cultures to our contemporary American world today. Through this, we can create our new American Dream.

Khash’s book is also for the Revolution. His book is for the Revolution in Iran, for the Revolution in America, and for the global Revolution of denouncing anti-immigrant violence and xenophobia in diasporic spaces everywhere in a world where our diversity is our strength. His book is for the Revolution of young people today, fed up with state violence against those who make up essential parts of our communities across many of our states.

Khash’s book welcomes everyone with one foot in their homeland and one foot in America, understanding the hard work our families contributed to our lives in America but also remaining curious about the world they left behind. Even more, this book is for those who seek to repair communities, allowing diversity to transform from difference to power, and embracing our diasporic identities in this necessary rejuvenation of American identity today, the New Americana.

What can you do?

See:

- “Close-Up” by Abbas Kiarostami

- “The Wind Will Carry Us” by Abbas Kiarostami

Hear:

- “American Love Song” by MOMO!

- “Baraye” by Shervin, Iranian Women’s Movement “Anthem”

- “Nails” by Saint Levant featuring Mia Khalifa

- “Ana Lahale” by Elyanna

- “Mystery” by Raveena Aurora

- “Haifa in a Tesla” by Saint Levant

Act:

- Read I Will Greet the Sun Again by Khashayar J. Khabushani

- Read On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vaughn

- Read more articles by Maia:

Do:

- Join local protests to support the Iranian Women’s Revolution for the one-year memorial of the killing of Mahsa Jina Amini

- Promote diverse diasporic identities by denouncing anti-immigrant violence and xenophobia

- Find out more about Khashayar J. Khabushani HERE