When I call Leah Penniman on a Friday afternoon, she is walking around her farmland in Grafton, New York. “We use Afro-Indigenous, precolonial, land-based agricultural techniques”, she explains as she walks around her crops. “There are shrubs and berries planted around the apple trees, next to twenty varieties of medicinal herbs, and natural pest repellents.” Leah’s farm couldn’t be farther from a monoculture, and still manages to provide affordable, fresh fruit and vegetables for the community around it.

Leah is the co-director and farm manager of Soul Fire Farm, an organisation that, since 2010, has worked to undo the structural, systematic racism in the agricultural and food systems. She has since been featured in the likes of Vogue and The Counter, written for Yes! Magazine and published a book about being a Black farmer, and even won the James Beard Foundation Leadership Award, an accolade that rewards innovative work in sustainability and food justice. In 2020, both COVID-19 and BLM shone a light on the inequalities and fragilities of the agricultural supply chains, which propelled the work that Leah has been doing for over twenty years into the eyes of the general public.

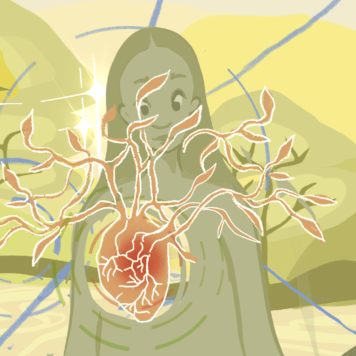

Like many Black and minority-ethnic farms, Soul Fire Farm has become a hotbed for agricultural activism and justice, essentially out of necessity rather than out of choice. The farming methodologies that Leah and her team champion see the ‘land as a relative, not a commodity’. While farming itself is often a practice that is inherited and passed down through generations, so is land as a form of property, and it’s perhaps no surprise that in nations with wide racial disparities, land ownership sits overwhelmingly with a white, upper-class. The UK, USA, South Africa and Zimbabwe are just a few to name, and all have deep-seated histories of land grabbing and classism.

For the team at Soul Fire Farm, their agricultural activism includes well-known practices such as composting, which returns nutrients from natural waste back into the soil. There are also deliberately anti-capitalist techniques, like the use of cover-crops, which are used to improve soil health rather than to be harvested and sold. Conversely, monoculture farming – where crops are produced solely to be sold on the market – focuses on efficiency, productivity and crop yield at the expense of long-term land and community sustainability. When supply chains are disrupted, monocultures prove futile: “Their rigidity and inability to be flexible according to demand is what led to shortages in the supermarkets at the outset of the pandemic,” Leah explains, “whereas localised food systems showed high resilience. We were able to quickly arrange no-contact pick-ups, repackage our online offerings, and focus on community needs and requirements.”

As supermarkets and food retailers have abandoned seasonal buying over the years, consumers – particularly in the West – have grown accustomed to having non-seasonal fruit and veg grace their supermarket shelves all year round. That, in turn, has led to a silent overreliance on agriculture-heavy economies in Africa, Asia and Central and South America, industries that are overwhelmingly reliant on minority farmers. Out of every four farms in the world, three are family-owned and operated. And as demonstrated by the ongoing protests in India, governments are doing little to protect these farmers and their livelihoods. In Western countries, the number of minority farmers has dwindled dramatically over the years – from a million Black farmers in the US in 1920, only 45,000 were left as of 2019. It’s a combination of unequal access to capital, closed-off farming networks, exploitative contracts across supply chains and reduced bargaining power that has routinely shut farmers of colour out, Leah says. “We’ve forgotten that we need to take care of the people feeding us”, she adds.

Plenty of research has been done on food deserts and food apartheid, the intersections between race and a lack of access to nutritious food, and the price gentrification of healthy food. But that is all on the consumption side, and it’s not often that we hear about exclusion on the producers’ side too. For Soul Fire Farm, this has been an imperative topic to cover in their intensive training programmes for Black and Latinx farmers. “We need to educate our farmers about market access and how supplier contracts work. In reality, large institutions are not going to buy from small, regenerative farms, because they are seeking uniformity” Leah explains. “95% of regenerative farms will end up relying on some external income just to get by, whether that is tourism or the provision of additional value-add services.”

The direct-to-consumer (DTC) shopping revolution, which sees producers communicating and shipping directly to their patrons rather than relying on intermediaries, has increasingly been a pillar of market access that Leah and others at Soul Fire Farm have relied on. As consumers look more for the stories of where their products have come from, and begin to scrutinise the global journeys that their food and fresh produce take, localised farming collectives like Soul Fire Farm can find ways to get compensated fairly for their labour and goods.

We’ve known for a long time that the food system is broken, not only from an economic and climate perspective, but also from the simple angle of care and wellbeing for those who tend to the land. When I ask her how she finds rest and peace in between all that she does, Leah answers quickly: she doesn’t. “We’re not getting enough sleep, and that’s a structural problem,” she adds. “In one generation of settler colonialism, 50% of the carbon in soil was released into the atmosphere. It’s our job as farmers, folks who are closest to that world, to put it back again. But we can’t do that if farming isn’t seen as a dignified and well-compensated career.”

See more of Naomi’s work on instagram