Last year, my mother got very sick, and it was scary. It got me reflecting on what my mother means to me and who she is.

I have often found myself reflecting on motherhood and being a mother. Not because I am a mother or plan on being one, but because I don’t think we afford motherhood the appropriate level of reverence – especially in the Western canon.

Unfortunately, the colonial project and its constant rebranding have hegemonic control over how we conceptualise motherhood, and rendered us unable to articulate its complex and reverential nature.

In my time of pain, anxiety and deep sadness for my mother, I found myself picking up Oyèrónkẹ́ Oyěwùmí’s What Gender is Motherhood (WGIM) again to remind myself of the “otherworldly, pre-earthly, preconception, pregestational, presocial, prenatal, postnatal, lifelong, and posthumous” relationship I have with my mother.

The only thing that could bring me peace was that my mother would remain my mother no matter the outcome.

Who is Ìyá?

Oyěwùmí discusses extensively and convincingly in The Invention of Women how the colonial project introduced gender constructs among Yorubas with their inaccurate translations of how we arrange our societies. We often conceptualise gender/sex as a binary and, sometimes, a spectrum with opposing ends; word and opposite; female and male; mother and father. However, motherhood for Yoruba people transcends the gender/sex category.

Ìyá is often translated as the Yoruba word for mother; however, these are not the same. The institution of motherhood in the English canon is represented as gendered by various dominant conceptualisations, feminist and non-feminist.

To gender the Ìyá, or reduce it to a gendered institution, is not only reductive to who an Ìyá is but, frankly, insulting.

Ìyá embodies what Oyěwùmí refers to as the matripotent principle. This concept reflects the spiritual and material authority of Ìyá that is derived from their procreative role. A particular emphasis is placed on the relationship between Ìyá and their birth children, as this expression of matripotency is considered the most potent.

Furthermore, the matripotent ethos is linked to a seniority system, as Ìyá is revered as being more senior to their children. Since all humans have an Ìyá, no one is greater, older or more senior than them.

The lack of gender pronouns and the presence of age and seniority-based pronouns in the Yoruba language should instantly make it obvious why Ìyá is better conceptualised under the age and seniority-based hierarchal system, not a gender based one. You are not an Ìyá because you are a woman; you become an Ìyá when you have a child.

Ìyá as a spiritual category

At the core, for we Yorubas, Ìyá is a spiritual category that transcends the simplistic understanding ushered in by modernity.

Fatherhood is simply a socially constructed position that could be negotiated through marriage rites and kinship. The social construction is further entrenched through evidence of women being fathers through woman-woman marriages in Yoruba history.

Women had a path to fatherhood through the marriage rites they performed with other (sometimes younger) women. This would involve the latter having intercourse with a relative or friend of the former. However, providing the sperm or a biological connection was not what made the person the father; what determined this was the marriage rites. Therefore, fatherhood was highly negotiable.

We can immediately understand why limiting either fatherhood or motherhood among Yorubas to gender categories is redundant.

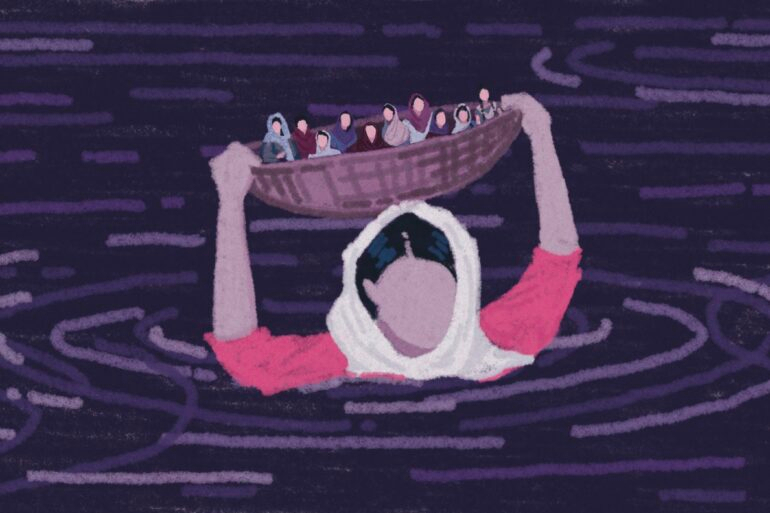

We can begin to imagine the spiritual possibilities and potential of the Ìyá. Ìyá is not simply one that gives birth to a child; Ìyá is a co-creator of the child and gives life with the Ẹlẹ́dàá (creator) because Ìyá is present at creation.

An aboyún (pregnant person) exists in a precarious position between the world of the unborn and the living. Spiritual and medicinal practices enacted during pregnancy and childbirth aid the aboyún in remaining rooted in the realm of the living during this life-altering and community-altering experience.

When a child is born, we congratulate the Ìyá on surviving the dangers of childbirth by saying, “ẹ kú ewu ọmọ.” There is no greater tragedy than an Ìyá losing their life as they create a new one.

When we say “ìkúnlẹ̀ abiyamọ” (the kneeling of an Ìyá in the pains of labour), it’s not a mere saying or figure of speech. This historically preferred position of childbirth is an act of reverence to solicit support from the orisas on the journey of bringing life into the world. It is not a coincidence that the day the Ìyá gives birth is referred to as ọ́jọ́ ìkúnlẹ̀ (literally translated to mean the day of kneeling in labour).

During childbirth, the Ìyá exists at the intersection between the realm of the unborn and the physical world. It is a dangerous position and should not be taken lightly.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

It is, therefore, postulated that Ìyá is the co-creator of humanity, serving as the source from which all humans are derived and thus functioning as an archetypal human being.

For this reason, the Ìyá is blessed with mystical resources to martial on their children’s behalf. No one knows you like your Ìyá because your Ìyá is present at your creation. Your Ìyá is your guide into the world and has the power to proclaim over you how you exist in this world.

The father cannot stand as an opposing institution, gendered or not, because these demands, or opposing but equivalent ones, are not asked of the father.

Essentially, fatherhood does not have the range to stand opposite to Ìyá.

Ìyá in Practice

The spiritual powers of mothers are symbolised by various Yoruba systems that exist today, such as the Gèlèdé festival, which celebrates the power of older women, àwon iyá wa (our mothers). The understanding of Ìyá here goes beyond biological motherhood, but evokes the political power of elderly women through public motherhood.

Public motherhood is where Ìyás no longer function as wives, but are devoted to their children, this often extends beyond the household and into the community. Much of this power is granted from their role as mothers.

Much of this public power is used to influence the decisions on Ọbas (rulers), marshalling on behalf of the community, managing conflict in the town and overseeing public affairs, such as market trade. We see this in the role of the Ìyálóde (mother owns the outside world), an important role in the council of the Ọba.

My Ìyá

I have been blessed to have an Ìyá that embodies this conceptualisation of an Ìyá.

When a child is born, so is an Ìyá. I have older siblings, so my Ìyá became an Ìyá long before I arrived, but my Ìyá became an Ìyá again when I was born.

My Ìyá is the person who taught me that the word “Chairperson” was her title, and not the implicit male burden it carries. Everyone knows who chairperson is for miles in Ipaja, and it’s not always the person with the current title, which is actually currently my Ìyá. Since my Ìyá became chairperson, she was forever the chairperson, whether she held the title or not.

My Ìyá is someone with the confidence to march into Alausa (the seat of the Lagos State Secretariat and offices of the Governor and Deputy-Governor of Lagos State) and successfully make the demands of the community known.

My Ìyá is the first feminist* I knew, who advocates for assault survivors, particularly gender-based violence. The abolitionist* known at Alagolo Police Station for not letting the police officers get away with their senseless and extortionate arrests, and instead focusing on community accountability, care, and rehabilitation.

She is the matron to countless youth groups, and the Yeye Atunwase of Ayobo Land. This is an official chieftaincy title my Ìyá holds as a member of the council of the Ọba of Ayobo. Yeye, another Yoruba word for Ìyá.

My Ìyá embodies the spirit of an Ìyá, not only to my siblings and me but to so many. I very quickly realised that my Ìyá was not simply my Ìyá but an Ìyá to many. Like many Ìyás in our community who evoke public motherhood, she is actively committed to the people in the community’s lives. This was not simply a product of her gender but based on her seniority, experience and impact on the lives of the people in the community.

The prayers of my Ìyá speak words of life into me and the community. As she prays, she reminds me of the day she was the bridge that brought me into this world. She reminds of her tears in pain as she knelt to pray for safe passage. She reminds me of the body that fed me for the first few months before I was ready to face the harsh realities of this world.

My Ìyá’s health is improving, and we believe the worst is behind us. But if this experience taught me anything, it is how much I take what my Ìyá means to me and who my Ìyá is for granted.

It is a shame life (read: the insidious nature of the colonial project and the age of modernity that saw to change, and not preserve the precious conceptualisation of my Ìyá) gets in the way sometimes. But through this, I know that no matter the outcome, by being my Ìyá, she will always be with me, physically and spiritually.

- Read What Gender is Motherhood by by Oyèrónkẹ́ Oyěwùmí

- Read The Invention of Women by Oyèrónkẹ́ Oyěwùmí

- Read Mother Is Gold, Father Is Glass by Lorelle D. Semley

- Watch Journey of an African Colony on Youtube

- Listen to the Reconceptualising Rotimi Fani-Kayode podcast by queer/disrupt