The earth below looks a deep terracotta from the window of our tiny two propeller plane, and only gets redder as we descend into Yida refugee camp in South Sudan. As we get lower, termite mounds are revealed to us, dotted around what otherwise looks like a sparsely wooded area. The air is surprisingly clear after seeing the burning landscape during the flight – the result of hunters chasing animals out of hiding by setting fire to the brush.

It was last December 2018, and my colleague Sonja and I were travelling to meet refugees from the Nuba Mountains, an area just over the border with Sudan.

The Nuba Mountains played unfortunate host to Sudan’s civil war with the south. This was a conflict underpinned by a racist ideology which painted Black Africans as interlopers on land dominated by an Arab elite based in the far-away capital, Khartoum.

When the countries split in 2011 and South Sudan was formed, the people of the Nuba Mountains were supposed to be given a free vote on which side to join, but instead were met with war, famine, and targeted by aerial bombardment from Sudan’s government. The population either stayed to face the bombs, were forced to live in caves for basic safety, or fled south.

Sonja and I are co-directors of Waging Peace, an NGO that has campaigned on behalf of the people of the Nuba Mountains since conflict broke out in 2011. We have also worked in other regions of Sudan, like Darfur, which Waging Peace first travelled to in 2007. For this trip we brought pencils and paper with us and asked the children there to draw their strongest memory. We returned with 500 images of the children’s experience of the genocide.

We wanted to see if something similar would result in Yida, over 11 years later. While Waging Peace normally offers support to refugees once they have survived the journey to the UK, this would not be possible for those either trapped in the Nuba Mountains or in the Yida camp. Therefore, we travelled to them – to ensure their voices would be heard internationally even though they themselves could never make the journey.

We spent five days with the children of the camp engaged in a sports programme run remotely by Raga, a Nuba refugee we knew from Britain, named Green Kordofan, which gives children the chance to engage in football and volleyball tournaments. It was in this environment that we asked the children for their drawings – wanting to better understand what was on their minds.

We received quite a worrying precursor to the images when a child, in front of a group of his laughing peers, threaded his hands through his flip flops, so that these lay flat against his forearms, and mimicked the act of running. Through laughter, we were told that this was the boy explaining how you would have to do this, so you did not get tripped up as you ran away from the bombs.

The 60 or so images we received often showed children running from bombs dropped from aircrafts labelled ‘Sudanese Government’. They showed someone’s mother being shot at as she collected water from a well. They showed conditions in the camp, where food distribution was often delayed by weeks. Political expediency forced the United Nations continually to downgrade the support offered to these forgotten people. Such support has since been removed entirely.

But they also showed the life these children lived before they were forced to flee.

In one picture ‘grandfather’s house’ is identified, in another the famous Nuba wrestler is celebrated, and in a third a family simply gathers under a tree to eat. A good deal of the images also showed the children’s favourite football stars, mostly Lionel Messi from FC Barcelona, likely connected with the sports project we were there to visit. We see this as testament to the fact that life continues, that this is a resilient people who refuse to be defined by the horrors of war.

The images bore a striking and devastating resemblance to those we had gathered in Chad from victims of Darfur’s genocide 11 years previously. Those had shown the way the government paramilitary force, the Janjaweed, would first enter camps, burning all that could be set alight, poisoning wells and driving out livestock, shooting at and killing any who did not run away.

Importantly, the images also showed the Sudanese government’s direct involvement. This was at a time when the Government was denying that this latest conflict was anything more than a skirmish between rival tribes. The children knew different, they drew artillery likes jets and helicopters, and armies clad in fatigues. They also drew the faces of attackers and victims differently – the villagers were rendered with blacker crayons, and the faces of the Janjaweed and army in lighter colours. The children could depict the racist ideology which made Darfur a genocide, even if they could not have articulated it directly.

The value of these images was immediately apparent to us, and to anyone who saw them. The International Criminal Court accepted them as contextual evidence of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. They were then able to contribute to the indictment against (now former) President Omar Al-Bashir, and the still outstanding warrant for his arrest. They toured schools, universities, and parliament buildings globally. But for years conflict in Darfur continued, and gradually international attention moved on to other crises.

The drawings from the Nuba children will signify something different for Sudan. Just after Sonja and I landed back in London protests broke out in Darfur. This time pressure built and the protests did not stop. They did not stop when Al-Bashir tried to scapegoat Darfuris for the violent crackdown on demonstrators involving the deaths of dozens – protesters just took to the streets chanting: “We are all Darfur!”. They did not stop when Omar Al-Bashir was forced from power on 11 April, 2019. They did not stop in June when the site protesters used as a base was stormed by the Rapid Support Forces, a rebranded paramilitary group who had incorporated the Janjaweed forces. And they have still not stopped today, as military forces caved to pressure to share government with civilian leaders. Sudan now has three years in which to establish a functioning democracy that is entirely civilian-led.

The drawings are, like the children who drew them, going to grow old in a very different Sudan. One in which hopefully the human rights and dignity of all citizens are respected. As we have for the past 15 years, Waging Peace will be supporting the British-Sudanese community to help their countrymen achieve this vision.

We will continue to use these drawings as a tool allowing the Sudanese community to heal past trauma. Already they have joined their Darfuri counterparts in permanent collection at The Wiener Library, the UK’s foremost Holocaust archive. There they are kept for posterity. We like to imagine that one day they will be returned to Sudan, where they will be a permanent record of the horrors wrought when people view whole groups as different, dangerous, or simply ‘less than’.

The revolution of this year has achieved much, but it is just a starting point – divisions between the urban elite and rural poor, and between ethnicities, remain. Unless Sudanese of all descriptions grapple with questions of identity and belonging, the political process in the capital will feel far removed from the lived reality of camps in South Sudan and Chad. By displaying these images, we are forcing this difficult conversation. These things happened, and they happened when we turned our eyes away. As we left the camp a woman living there said: “tell the world about us”. We will start by telling you and hope you will tell others too.

By Maddy Crowther, Co-Executive Director of Waging Peace, an NGO that campaigns against human rights abuses in Sudan and supports Sudanese asylum-seekers and refugees to build meaningful lives in the UK. If you are interested in displaying the children’s drawings, or images of whitewashed art from the sit-in site in Khartoum, please contact her on maddy.crowther@wagingpeace.info.

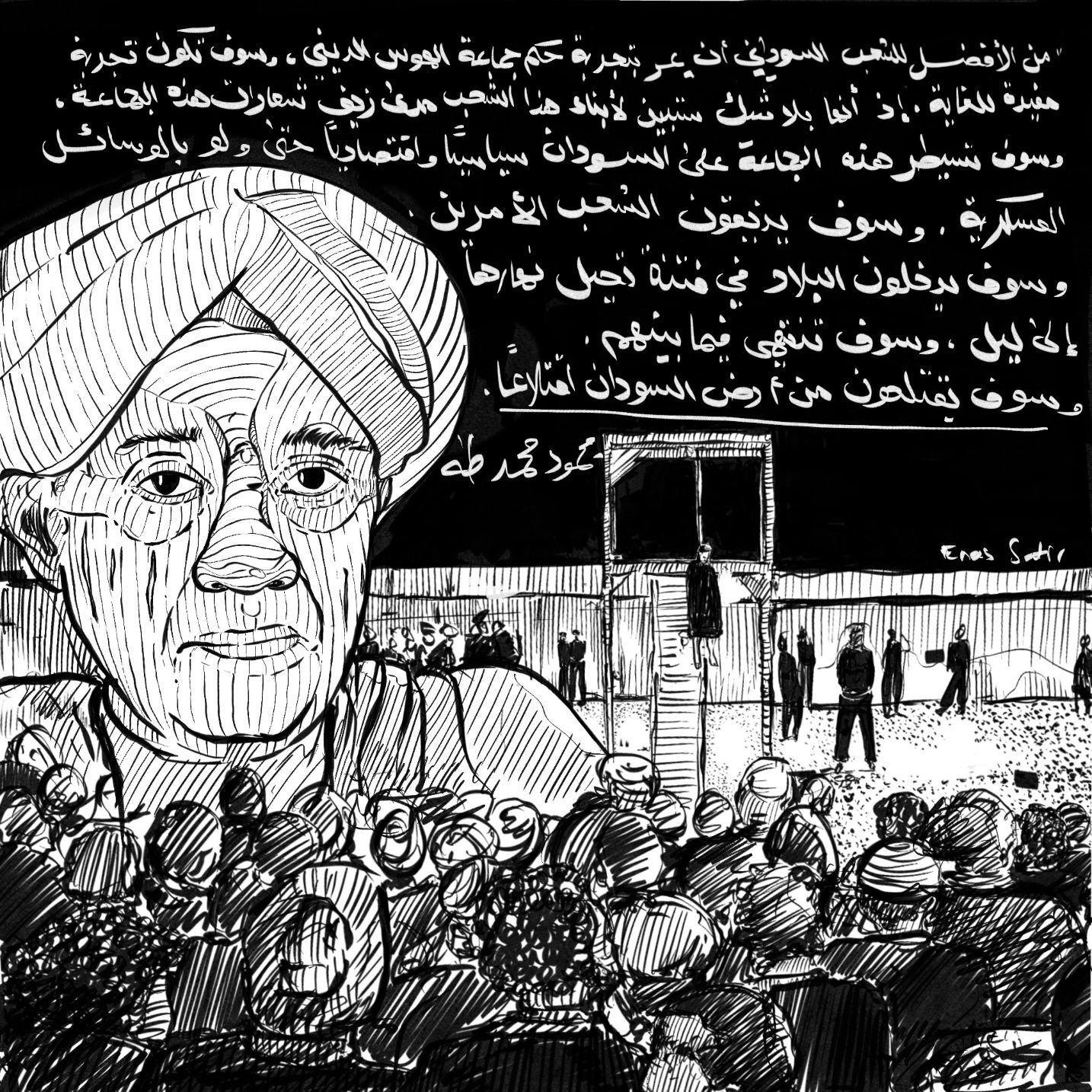

See more of Enas’s work on her instagram here

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.