It was a momentous day to be entering The Houses of Parliament. That afternoon 10,000 people would amass in the streets protesting Britain’s new Prime Minister Boris Johnson, exercising their right to freedom of speech by showing their anger against a government they felt was non-representative.

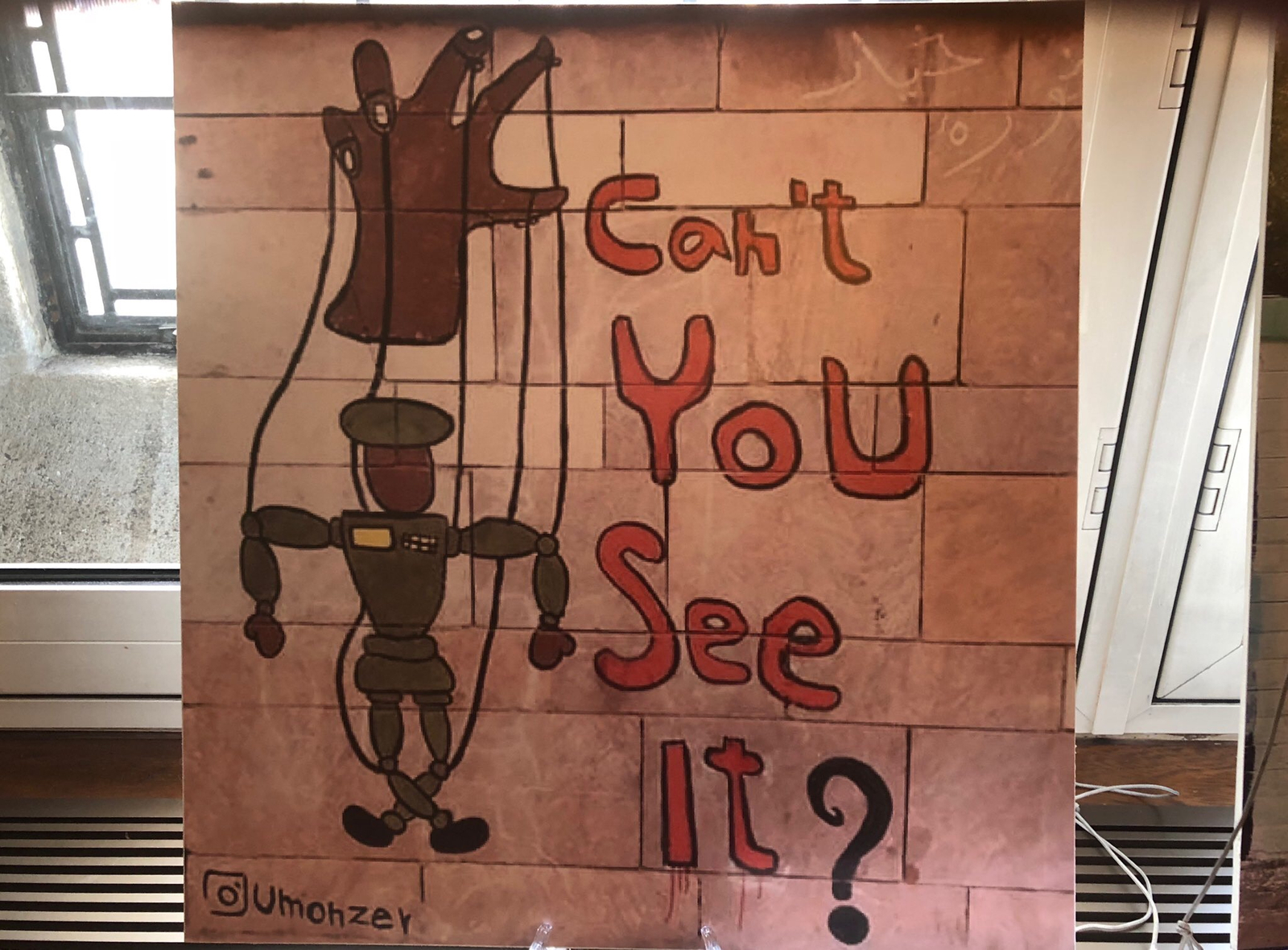

In stark contrast, on display inside the walls of parliament was evidence of how people exercising that same right have been persecuted in other parts of the world. Lining the walls of the IPU room, among busts of government officials, was photographs of now demolished street art protesting the regime enacted by Omar al-Bashir. Alongside these photographs were children’s drawings, evidencing the atrocities committed by the same regime in regions like Darfur.

The exhibition was put together in collaboration with the Sudanese Doctor’s Union UK Branch, members of the Sudanese Diaspora and the NGO Waging Peace, with the aim of forcing government interaction with atrocities committed in Sudan, atrocities that have been easily dismissed in the past. The exhibition had recently been put on at SOAS, with plans to return there in early September. Since it’s first display the exhibition has gained significant attention, with plans to take it to Geneva and Brussels in association with the U.N.

Nada Elhag, from the Sudanese Doctor’s Union, states that the objective of the exhibition, apart from raising awareness in Britain, is also to help the Sudanese diaspora heal. “We’ve been through a lot, with the listening or hearing about what happened back in Sudan and […] seeing all these bad pictures without knowing what’s happening to family and friends.” More important even than this however, she states,

“is to honour our martyrs who died for a dream which we hope will be achieved soon”.

Aside from the photographs and children’s art, was a powerful audio-visual piece entitled ‘58 days in 15 minutes’. Encapsulated by the title, the piece is a recording of people chanting as part of a sit-in in Sudan. This is then interrupted by screams and gunfire. The audio component gave the exhibition a further cause for reflection, recreating the atrocities perpetrated on the streets of Darfur in the halls of British democracy. As Reem, a volunteer from the Sudanese Diaspora, states, “it’s another lens into the Sudanese Revolution that’s missing in mainstream media”.

The children’s drawings were collected as part of a research initiative conducted by Waging Peace. Their subversive quality helps outline the fracturing reality of conflict, as Reem points out, children who should be drawing scenes of animals and houses are instead depicting a massacre.

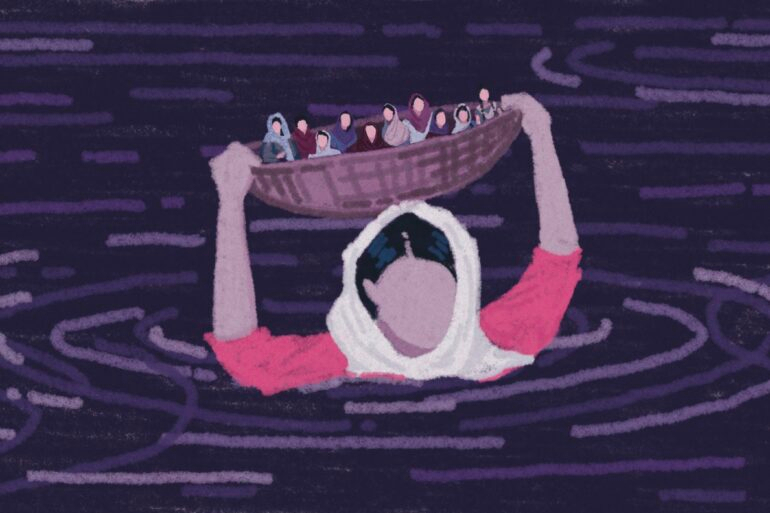

Sonja Miley, Co-Executive Director of the NGO, stated that upon arrival in Sudan Waging Peace had initially wanted to record women’s experiences of the conflict. However, the women merely answered with “ask the children”. The researcher then came back with over 500 illustrations, which quickly came to be known as the ‘Darfur Children’s Drawings’; some of which were on display as part of the exhibition.

Sonja went back to a refugee settlement near the border with Sudan in late 2018 with the idea of replicating the research with refugees from the Nuba Mountains, an area in which civilians have been similarly targeted.Instead of asking the children to draw their experience of state violence they asked them to draw whatever they felt like. Devastatingly, the images returned were largely the same. One of the most remarkable things about the drawings is their explicit detail. Aside from eliciting a powerful emotional reaction from the viewer, this detail, Sonja explained, allowed the drawings to be used as contextual evidence in the ICC tribunal against Omar al Bashir. “The kids drew the lighter coloured skin of the Janjaweed, who are of the Arab tribes, actually persecuting the darker-coloured skin of the civilians, […] they take your breath away.”

Sonja went on to explain that Waging Peace hopes that by displaying children’s art from different communities, ranging from Darfur to Chad to Khartoum, they can remind the viewer that this is not a singular conflict and has, in fact, been going on for decades.

By placing the art within Parliament, the Sudanese Art Refugee collaborative movement hopes to display the magnitude of the crisis and as Sonja states, “ask more questions of our own government and what they’re planning to do about it”.