Throughout human history, we have witnessed the destruction of natural resources as a means to achieve ‘civilisation’ and ‘progress’.

As a person from so-called Mexico, who currently lives in the United States, from my limited geographies alone I can speak to multitudes of atrocities committed on Indigenous land that have been justified in the name of capitalism. The deforestation of my own territory in the name of avocado production, creating water scarcity in favour of oil production, exploitative mining practices – the list goes on. Which is why, as I begin to write this piece during what the US recognises as ‘Native American Heritage Month’, I can’t help but notice the hypocrisy: countless Indigenous people across the ‘Americas’ or Turtle Island are still having to fight for land sovereignty amidst this ‘memorial month’.

‘Native American Heritage’, or any Indigenous heritage for that matter, can’t be disconnected from the essential issue of land rights. As more Indigenous people across the world recover languages, traditional foods and forms of art, a disconnect will remain if Indigenous people are not allowed to practice these ways of life in their traditional lands.

Self-determination and land sovereignty

Indigenous people taking their ‘Land Back’, aside from being an act of knowledge preservation, is also at its core a call for the dismantling of capitalism. By reclaiming self-determination over natural resources, Indigenous communities are slowing down and reversing the exploitation of the Earth. Which is why regardless of how much ‘green’ embellishment politicians and corporations add to their plans to extract natural resources, or how much potential revenue can be gained, the point remains the same: extraction of natural resources is a threat to Indigenous sovereignty, and therefore a threat to climate justice.

It is this forced extraction of resources on Indigenous lands which is currently taking place in the Amazon rainforest, particularly the region located on the borders of Ecuador.

During the months of July and August 2021, Ecuadorian President Guillermo Lasso issued two environmentally focused orders known as Executive Decrees 95 and 151. Both of these laws aim to promote ‘economic progress’ in Ecuador by transitioning the control and expansion of natural resources to foreign oil and mining companies.

Political greenwashing

To understand the impact this is having on the land and local communities, I decided to speak to two key activists on the ground. Manari, political and spiritual leader, and Indigenous defender of the Amazon, and Luciana Grassi, actress, activist and one of the founders of Emergencia Amazonia, both fight to defend the affected land and advocate for indigenous rights to address the climate crisis.

As we begin our conversation, Luciana attributes political corruption as one of the key drivers of the problem. She explains, “politicians and corporate owners have made the concepts of sustainability and social responsibility into a “marketing game” – so much so that as a society we have had to come up with the term ‘greenwashing’ to define it.

On the surface, both decrees promise ‘socially responsible and sustainable methods of oil production’ and vow to support the local mining industry by stabilising Ecuador’s economy. However, in reality Amazon Watch have revealed that the fineprint in “both decrees enable institutional channels to expand extractivism”, which continues to exploit local communities, the land and will allow for further extraction of fossil fuels from the ground.

Due to the deliberate duplicitous wording of these decrees, the gravity of what they could lead to and enable is left largely hidden. Luciana herself admits that if she was not connected with specific activist spaces, she would not be aware of how capitalist-driven government policy is actively and continuing to contribute to the climate crisis.

Media silencing

According to Luciana, the local media channels make it almost impossible to find out about the impact of these decrees. With next to no local reporting on these issues, it comes as no surprise that there is also a refusal by mainstream media to platform the Indigenous voices critiquing these policies.

When I undertook my own research, the majority of articles I came across were from economic or other academic journals and news outlets from English-speaking countries.There was nothing I could find in Spanish or written by someone on the ground. But, when you dig a little deeper this lack of reporting from within Ecuador is not entirely surprising once you learn who owns the mainstream media outlets and what their relationship is to politicians.

Exploitation under the guise of economic progress

Globally we have seen exploitative and harmful climate policies continue to be passed under the guise of economic progress. In Ecuador, Manari, explains it is no different; “President Lasso is promising that these decrees will increase the job market and economy for Ecuadorians, when in reality the rich individuals in the country will only become richer, while the exploited working class and Indigenous people will see little to no profits.”

News outlets are failing to inform the public on the realities of the situation or hold a platform to discuss such policies. Instead, they are working to convince the general public that further exploitation of natural resources will create economic opportunities for everyone; a message which becomes only more compelling as wealth disparities increase.

In the intentional absence of platforms which amplify Indigenous voices, we are witnessing the continued cover-up of the harms these policies are having. Without access to Indigenous knowledge, the general Ecuadorian public might be left thinking: why should I care about the Amazon rainforest? The truth is, we are all dependent on it.

This is something Manari, and other Indigenous land defenders know well: “When petroleum is extracted from the Earth, part of the energy that holds the Earth together is extracted, creating a ripple effect. When we destabilise the Earth, we destabilise our own energy as we walk on the surface of the Earth.” Simply put, by allowing further deforestation of the Amazon, we are only feeding the climate crisis and the natural hazards that are to come as we create yet another major shift in our planet’s climate patterns.

What you can do?

Those of us who are reading this article in the Global North must think about our role in this situation and the parts we have to play. We must leverage our own positions and hold to account the companies that are primarily benefiting from these laws.

It was very clear through my conversation with Manari and Luciana that the most important thing we can do as allies in this moment is to bring visibility to Indigenous people who are resisting the exploitation of natural resources in Ecuador.

The need for international solidarity

It is crucial that we strengthen our networks of international solidarity, because as Manari says, “we are all impacted by the deforestation of the Amazon.” We must work with the resources we have to ensure that Indigenous people are put back in their rightful place as the original stewards and protectors of their traditional lands, not just in Ecuador but across the world.

Political figures in settler nations like Ecuador will continue to find ways to take land from Indigenous people so that they can enact laws such as No.95 and No.151 without any resistance. But if we ensure that the land is under Indigenous ownership then First Nation communities can be afforded the power and self-determination they need to protect life-giving natural resources from exploitation.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

Most importantly though we must ensure that our dreams are of a different world, of a healed and sovereign world. We are not just at war physically but also spiritually. As Manari explains: “life is fragile, and the land is so fragile. There are so many humans on top of a larger spiritual being, [the Earth is a spiritual being itself] and our bodies are composed of spirits too”.

We must take care of our spirits and of each other in this fight. As much as we show empathy and love for the land, we must hold that love for ourselves and for one another. As Manari makes clear, the future of the Amazon and ourselves are one and the same. We cannot undo the exploitation of the land, without recognising the exploitation on our bodies also.

To find out how to support the work being done by Manari and Luciana and communities on the ground head to Manari’s website, or visit the Sapara nation’s website.

Spanish version available HERE

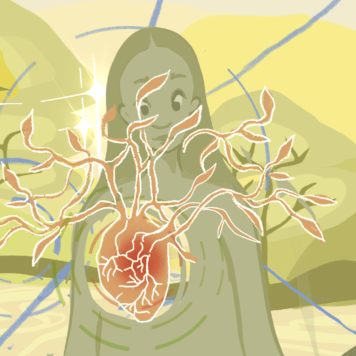

In the image the artist has represented people from the Sapara nation. The image specifically references money/capitalism as the cause of deforestation. The focus is on the people themselves, by having them and nature take up most of the frame. There are also references to spirits and dreams through the mist at the bottom of the image. Manari talks a lot about the spirit of the jungle, the knowledge of the spirit of the jungle, and that everything has a spirit. The possibilities of dreams is very important for the Sapara nation as it provides a clean technology for humans to communicate with others and change our reality.