Man Made Disaster, an exhibition hosted by Do The Green Thing, is a powerful response by 30 women and non-binary artists who operate at the intersection of creativity and social change (read more here).

Megan Conery curated the poetry commission for the exhibition, co-ordinating the work of 5 brilliant artists (Shagufta Iqbal, Sabba Khan, jasper avery, Amani Saeed and herself) and their responses to the inherent gender gap in climate action.

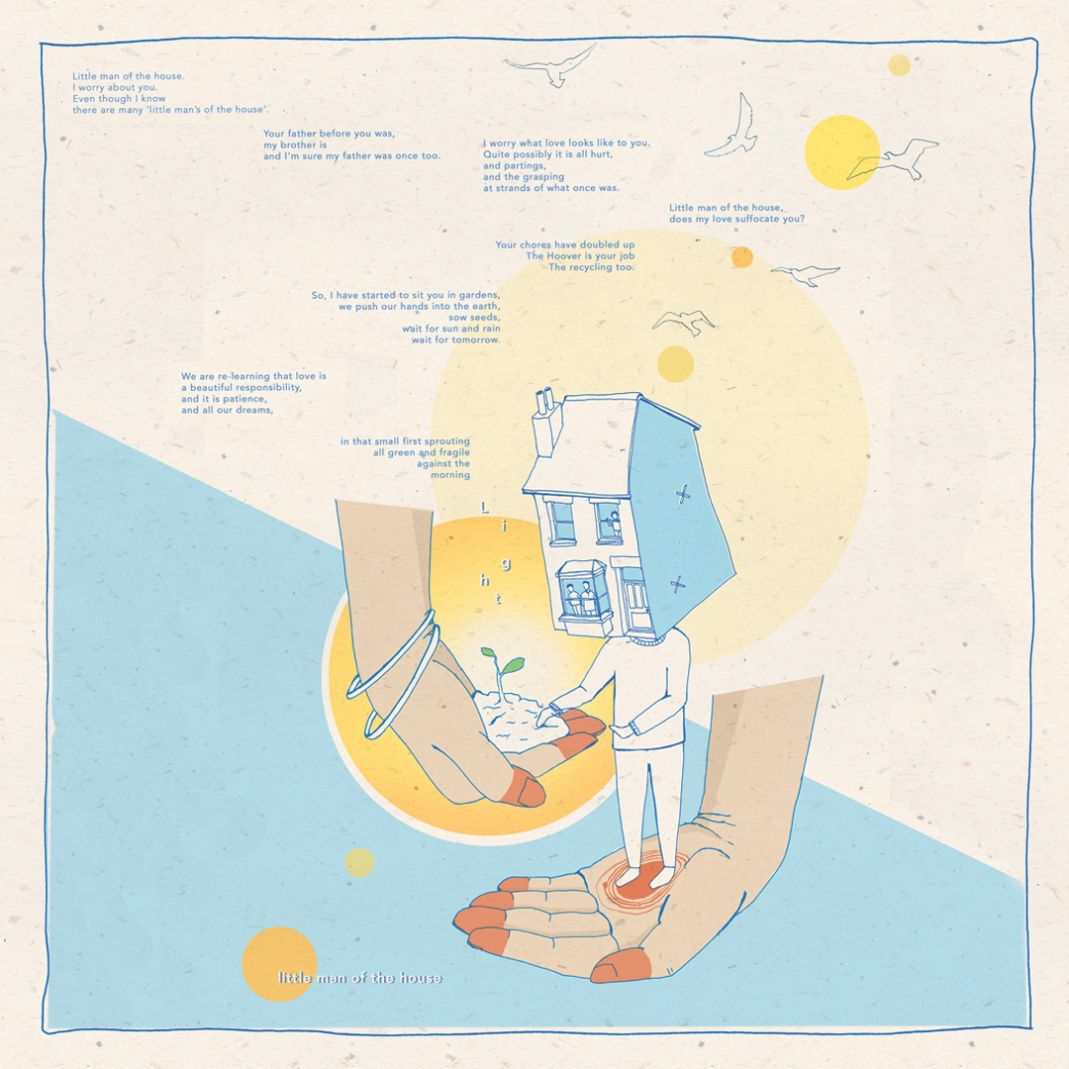

1. Shagufta Iqbal and Sabba Khan: Little Man of the House

Shagufta’s poem looks to break down the cycle of violence and becomes a eulogy to the power of love and healing. We are asked to re-imagine our concepts; Love is redefined as a space to feel free rather than constraint or expectation. Masculinity redefined as a vulnerability and gentleness. And ultimately Motherhood, reshaped as a growth, an expansion of one’s self and one’s offspring, rather than a perpetuation or passing down of fear, hurt and insecurity.

Sabba’s art is a response and a visual continuation of the nurturing and loving voice in Shagufta’s poem. In the art, the domestic home (usually representative of feminine space) is inverted to represent the built environment, containment, and masculinity. Her boy, heavy headed with the weight of gendered expectations, with his father, brother, uncle looking out through the windows of the house, is held in a loving embrace by his mother. Mother, with earthly henna adorning her hands, comes to represent the outdoors, nature, the sun, and ultimately divinity.

Both poem and art celebrate Mother Earth, and how she teaches that even after destruction there is healing and growth in the nature around us.

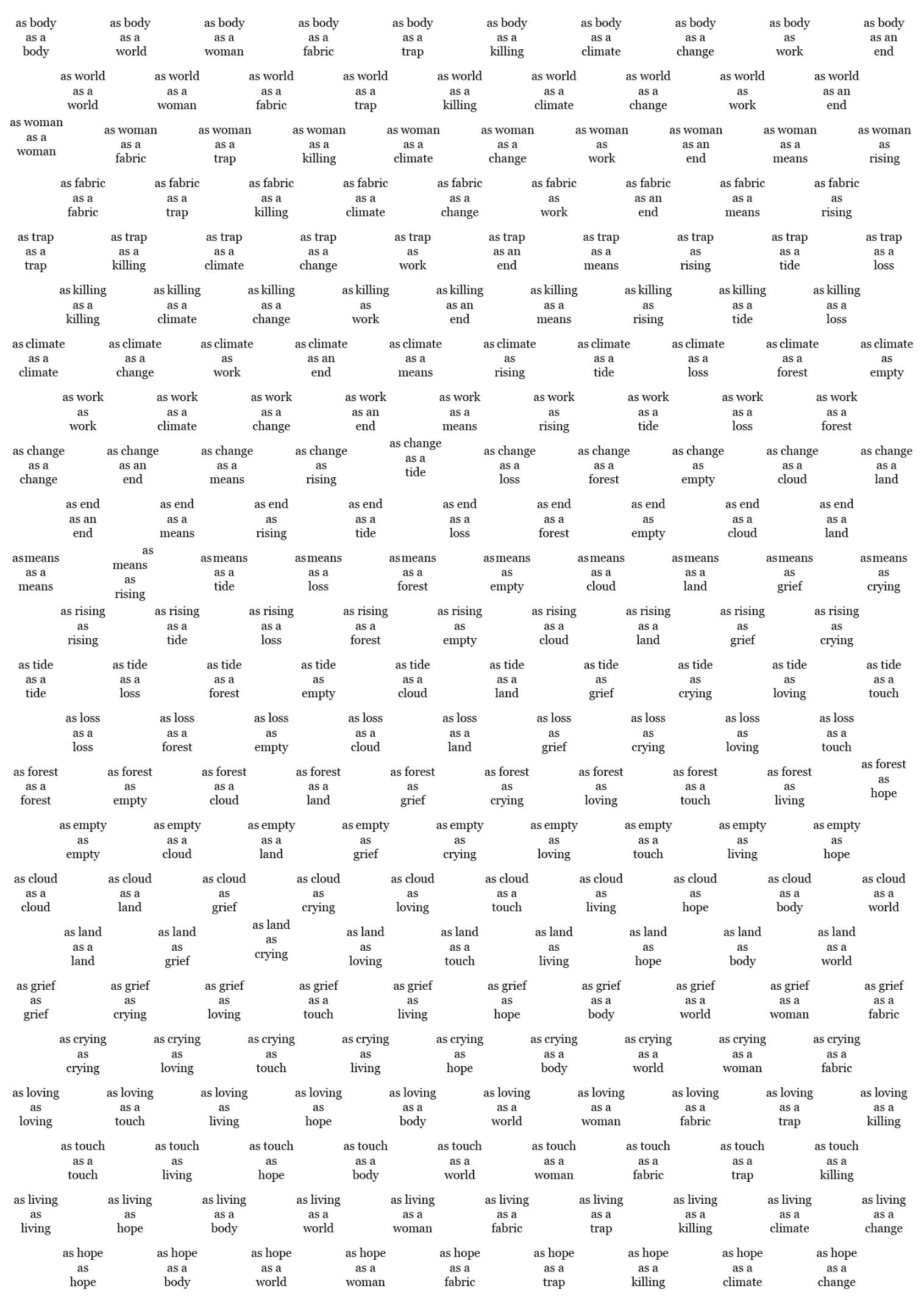

2. jasper avery: quilt

how do we, the women of the anthropocene grieve the histories of violence that have brought us here—in truth, holding things that are too big for one person has always been a woman’s work, sewing together the contradicting quilts of trauma and care that have defined all life as a human animal—there are many such feelings that are too big for one body to hold—grief is one of these feelings and gender is another altogether—by this i mean to say we women pass these feelings from body to body—i hold your grief and you hold mine—i hold your gender and you hold mine—when i say the word “pass,” as in, we pass these things from body to body among one another, you are free to substitute the word “passion,” as in we passion these feelings from body to body—but the question becomes: how do we grieve for a grief that is yet to fully arrive, and that is also already passed—a grief that started with the industrial revolution, or perhaps earlier, and has yet to realize itself fully, and will do so in ways we cannot yet hold, let alone pass—similarly, how do we hold a gender that is elsewhere, a gender that is for me and many others, mediated by the pharmaceutical industrial complex, and travels the oceans many times over— this is the question i am getting at when i say “there are feelings that are too big for one body to hold”—if the future is a kind of quilt, who is doing the sewing. where does the fabric come from—non-european countries, after all, will likely bear the brunt of the impending ecological catastrophe—that is, there is nothing coming to save us but us—this can inspire action as much as it inspires despair, a quilt has always been a patchwork, there are many fabrics that one can make into a whole—that is, can grief coincide with culpability—it must—can hope coincide with defeat—it must—there is as much creation to be done as destruction, as much mending as there is cutting a new cloth altogether—most importantly, caring can a kind of palliative and restorative both—caring must hold us together, the thread in the quilt each of us is sewing from where we each of us stand—if there is to be a future we must care for each other in it as we must care for each other now this can be, must be, enough

this quilt is dedicated of all marginalized women, trans, black and brown, poor, disabled, and mentally ill, displaced, immigrant, the ones who are no longer with us, and especially to those who tenaciously survive and make the world a better place.

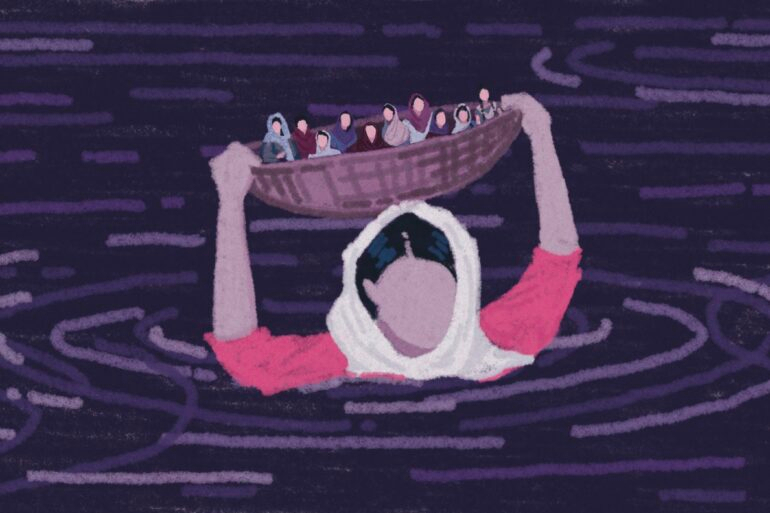

3. Amani Saeed: Failla Para

In part of Bangladesh, women living closer to bodies of water have an increased rate of miscarriage compared to those living further inland. This difference, scientists believe, is to do with the amount of salt in the water the women drink – the increase of which is caused by climate change. When sea levels rise, salty sea water flows into fresh water rivers and streams, and eventually into the soil. Most significantly, it also flows into underground water stores – called aquifers – where it mixes with, and contaminates, the fresh water. It is from this underground water that villages source their water, via tube wells.

4. Megan Conery: Beneath Concrete

I’ve lived next to the Blackwall Approach (southside) for going on 8 years. It’s a fixture in my life to the point that it’s become a fixture in my subconscious too. The traffic overhead is constant, punctuated by occasional blue and red lights. The flow of cars is a regular reminder that the air is laced with engine exhaust.

Some fun facts:

Isn’t it ironic, how phallic tunnel digging is? Don’t you think?

More than 100,000 cars use the Blackwall Tunnel every day

Air quality is being linked to up to 40,000 deaths in the UK each year

The original tunnel (1897) zig zagged to stop horses from bolting to the end

Roads are records of what came before – the streets that were truncated can’t be walked – they exist in memory, maps and deep dives into Internet ephemera

The Blackwall Tunnel is considered to be one of the worst tunnels in Europe by commuters

The 1970s expansion was sold as propaganda to the community with brochures promising utopian walkways and every kind of concrete finish

What would our city look like if its design wasn’t dictated by the patriarchy?

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.