When European forces barbarously colonised Africa, enslaved women found a beautiful, bittersweet way to retain connection to their lands and lifeways: they braided seeds into their hair. Today, a new wave of Western invasion is underway. This time, it has come for the seeds.

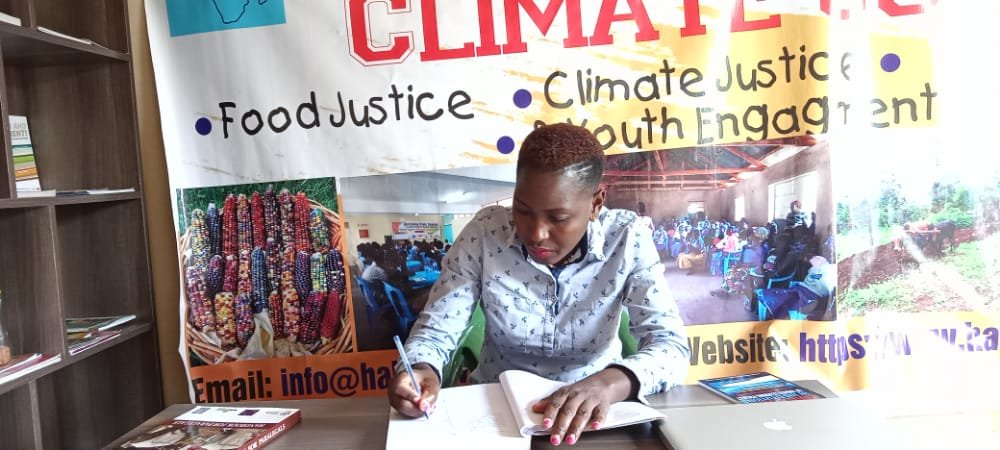

“Africa is being recolonised,” activist Leonida Odongo tells me over Zoom, from her home in Nairobi, Kenya. It’s late in the evening. As she often does, Leonida has returned from a long day in the field. Quite literally: she’s been visiting farms, helping smallholder farmers to reclaim sovereignty over their practices and resources.

A new form of colonisation

“This new type of colonisation,” she continues, “is coming in terms of technology, information and narratives. Our form of agriculture has been demonised, and derided as ‘backward’. We’re told we must adopt technology, use GM crops, and spray chemicals and pesticides – even though our Indigenous practices have worked for 10,000 years.”

Despite this long, successful history of organic farming, the past century has seen seismic shifts in how we grow and distribute food. Whereas farmers around the world used to have ownership over the seeds they used, in the 20th century, control was wrested from the hands of millions of individuals by giant biotech and chemical companies, like Monsanto and Syngenta. Today, as biologist Tyrone Hayes notes, 90% of seeds used to grow food are owned by these international goliaths.

How companies are controlling the narrative

Hand-in-hand with controlling the physical resources, these companies are also controlling the narrative. And they have a vested interest in demonising Indigenous knowledge – with its cyclical, reciprocal, regenerative processes – to promote reliance on single-generation-use hybrid seeds, and chemical pesticides and fertilisers.

In Kenya, chemical companies maintain narrative control by taking advantage of the lack of available information. Leonida explains that this is due to digital inequality (fewer than a quarter of Kenyans have internet access), along with the lack of accessible, affordable agricultural extension services (a result of recent Structural Adjustment Programs-SAPs).

She explains that “anybody who comes with information, that becomes the gospel truth. If I come with information about hybrid seeds, the farmer will believe everything I tell them, because they don’t have a credible alternative source of information.”

It gets worse. “The corporations come to your farm and tell you that they’re going to support you. They give you seeds and they give you chemicals, and they say that you can pay them back when you sell your produce. It’s like a form of a loan. But there are times (often due to the effects of climate change, which these companies are fuelling) that people can’t produce enough crops to pay back the loan. So their land is seized. It’s traumatising.” Mirroring the tragic surge of suicides among Indian farmers, Leonida tells me, “There have been incidents where women have taken their own lives because of these loans.”

The autonomy in Indigenous upskilling

Leonida is returning power to farmers by re-skilling them in how to be independent from chemicals, and to save their own seeds. She’s dedicated years to movement building, advocacy and education, including being part of the Seed Systems & Agroecology Working Group and Climate Action Group at the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA). She also co-founded Haki Nawiri Afrika, a social enterprise that (among other things) provides practical and political training for farmers that centres agroecology, seed sovereignty and Indigenous knowledge.

Leonida believes that this grassroots approach is the only way forward, because “there’s such a disconnect between farmers and the government, that the necessary change must come from the ground up.”

To say there is a “disconnect” seems a polite understatement. The Kenyan government, Leonida goes on to explain, is more focused on the economic value of the farming industry than farmers’ and citizens’ welfare.

Put simply, “they’re putting profits before people” – and smallholder farmers “sit at the bottom rung in terms of government support. If you look at the Kenyan Crops Act and Seeds Act, farmers’ voices are muted. Legislation is turning farmers into puppets, simply recipients of corporations’ instructions.”

Run-ins with the law

The lack of legal protections for farmers includes outlawing farmer-managed seed systems (FMSS). “There have been instances,” Leonida tells me, “of people being arrested for saving and exchanging seeds.” A practice that – far beyond being an industry process – is “part of the DNA of an African. From birth ceremonies to burial ceremonies, seeds are woven into our culture.”

Leonida explains that the required change at grassroots level must involve consumers as well as farmers. At present, she believes that consumers aren’t valuing organic produce enough to pay extra for it. “So, we need to educate consumers on the value of nutritious, safe, chemical-free food, and the importance of knowing where your food comes from. We’ve had scandals where vegetables have been grown in a sewer, so promoting a solidarity economy is a win-win.”

How Western influence is affecting nutrition

As well as financial considerations, Kenyan consumers are increasingly valuing food based on Western ideals, shunning organic, indigenous vegetables in favour of Americanised diets.

“There are many children under the age of five who are malnourished, but it’s not because there is not enough food. The problem is in people’s eating habits… many prefer to eat KFC.” Leonida regales me with the recent story of when Kenyan KFC ran out of potatoes, and instead offered indigenous alternatives: ugali and maize. There was “uproar”, she says.

That’s not the only way Western influence is affecting the nation’s nutrition. After almost a decade of genetically modified (GM) plants being outlawed in Kenya, in 2021, the country’s biosafety authorities approved the use of GM cassava, in what was reported as a “big win” for its smallholder farmers.

Leonida disagrees. “They’re talking about benefits in terms of scale and productivity, but nobody’s talking about the negative impacts on the environment, nobody’s talking about the chemicals going to water bodies that people, livestock and wild animals drink from. We’re finding a significant increase in cases of cancer – especially amongst children – which can be traced to food.”

The loss of granaries

A further impact of cultural colonisation has been the loss of granaries. “In the African context,” Leonida explains, “a granary symbolised adequacy of food. In African traditional systems, you cannot visit a homestead and leave without being given food. You could go to that store and get food.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

In African traditional systems, you cannot visit a homestead and leave without being given food. Now, if you go around Kenyan villages, granaries are no longer there. If there’s a huge harvest, people have to sell it all, then later go back to the market and buy back the food they would have stored at exorbitant prices. “Additionally, the culture has changed: you can now visit a house and leave without being given anything to eat.”

The newly imposed emphasis on monocultures – the practice of cultivating just one type of crop across a given area – is also creating problems, including a need for middlemen. People within a community are no longer able to trade among themselves, and subsist off their own produce. Instead, “an entire country will be growing maize… it means that there’s not going to be a market for the products until and unless you get them to an external city market.” For most Kenyan farmers, this means selling to money-grabbing middlemen.

Threats posed by modernisation

Modernisation also threatens to make farmers redundant. “If you talk about using sensors, for example, to know the soil moisture, or GPS to find out information about the land, you can cut farmers out.” Moreover, farming in Africa is about connecting with nature: “When a farmer touches the soil, turns the soil, he or she is connecting with nature. Technology-based farming in essence deprives farmers of this important connection.

As in most African countries, the agricultural sector is the backbone of Kenya’s economy: it directly contributes over a quarter of the nation’s GDP, and employs over 80% of its rural workforce. Given this power, why don’t farm workers simply go on strike? Leonida explains: “In Kenya, if I go on strike today, there are 5,000 people, or 10,000, who will come looking for the same job. The possibility of not getting that job tomorrow – of not being able to put food on the table – is very, very high. That makes collective bargaining a huge challenge.”

The problem also loops back to the lack of available information and connectivity. Environment Africa has started running a successful scheme in Zimbabwe, which provides farmers with radios that broadcast information on environmentally-friendly growing practices and ‘Indigenous Knowledge Systems’. This includes avoiding hybrid seeds and chemical fertilisers, and practising intercropping and crop rotation.

The strength of community-building

Leonida has successfully started to build community between farmers, shifting their perspective from a “one family, one man, one wife affair” to a communal mindset.

She does this through hosting seed forums, or “takafari” (a Swahili word for reflection), in which farmers gather for group learning, discussions and problem solving. Everything the farmer learns, they put in place on a section of land, and act as thought-leaders and knowledge-sharers in their village and beyond.

“The response is exciting,” Leonida beams, explaining that many of the farmers she works with have stopped using chemicals, and started storing their own seeds.

Where the movement is going

So, how can we help? For a start, Leonida says, it’s important to open up discussions in which traditional agroecology is not seen as “backward”, but as valuable and valid.

At present, the European mindset doesn’t regard African agriculture or farmers as equals. African farmers are forgotten about, and treated as inferior. For instance, Kenya supplies a third of all cut flowers sold in Britain. British people get the benefit of the beautiful blooms, without any of the associated pollution, land loss or exploitative working conditions.

“Some pesticides have been banned in Europe, but they’re still being exported by the same companies into the African continent. It’s often said that Switzerland makes the best chocolate, but the question is, just how many cocoa bushes does Switzerland have?”

We have much to learn from Indigenous agroecology. Indeed, it was enslaved West African women – with their rich generational knowledge in cultivating the seeds that connected them to their agency and culture – who were responsible for the success of rice farming overseas. It’s time for Europeans and Americans to speak out against this new colonisation, and return seed sovereignty to African hands.

What can you do?

Read:

Find out more about climate justice in shado Issue 03

International Seed Day Versus World Intellectual Property Day

Agroecology in Africa has a Female Face

Fighting for Food Sovereignty in Kenya and Uganda

Building Women Capacity for a More Sustainable Food System

Food Crisis: Weaving a Web of People’s Resistance to Corporate Agriculture

Climate Change and Human Rights: A call for International Solidarity

Changing to Sustainable Farming with Leonida Odongo

Watch:

Who decides what farmers grow?

Other:

- Follow Haki Nawiri on Facebook and Twitter

- Engage in our activities or organise a fundraiser: contact info@hakinawiriafrika.org

- Become a Friend of Haki Nawiri and support their work in rural settings and urban communities

- Link Haki Nawiri with donors and other development partners in your country

- Invite Haki Nawiri project participants to your activities

- Learn directly from Leonida’s organisation, and share information about their work with those who can support it.

- Create and join discussions that amplify information about food sovereignty and agroecology – to bridge the North-South divide and dissolve the narrative that African farming is “backward.”

- Donate to the cause of advancing agroecology and food justice in Africa

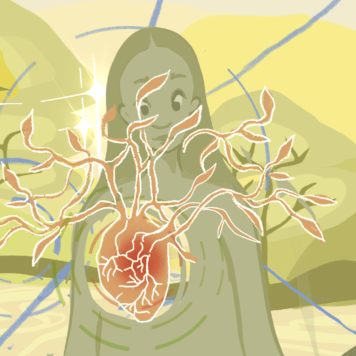

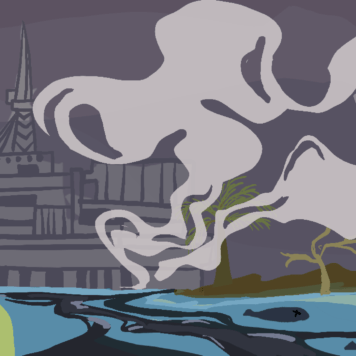

The artist’s goal was to depict an image that reflects what is happening in smallholder farms in kenya, the image details the negative effects of the pesticides and chemicals introduced by big business on the workers and the crops. The farm works no longer have autonomy or ownership over the crops they are trapped operating in a way dictated by the big business and this has detrimental effects on them and the local biodiversity. The artist used a repetitive pattern to represent the repetitive, predatory nature of their practices.