What we watch plays a massive role in determining our relationship with nature. As the environmental movement has gained traction over the last decade, mainstream film and TV have begun to parrot more progressive sentiments. Yet, they often centre white, corporate and patriarchal narratives that can actually be counter-productive.

This is why we have decided to delve into the wonderful world and works of global womxn and non-binary independent filmmakers who have yet had the opportunity to take the global stage. First, however, we want to demonstrate the issues with mainstream environmental filmmaking over the last decade.

A classic example is Blue Planet II. After streaming in 2017, David Attenborough managed to inspire what seemed like the entire population to take a long look at the effects of plastic pollution. In the year after its release, the UK saw a massive 53 % reduction in single-use plastic usage which became known as the “Attenborough effect”.

Sure, Attenborough’s documentaries spark a deeper emotional investment for our planet, but they continuously fail in acknowledging that humans are part of natural systems. In doing so, it reinforces the European-Christian colonial conception of nature – its value is in it being ‘untouched’ – that was used by Britain to evict Native American people from their lands in the name of “conservation”. Further, his more recent A Life on Our Planet platformed the idea ‘overpopulation’ was the major environmental threat. Arguments such as this deflect responsibility from the major polluting activities of the global 1%, to countries in the Global South where the population is growing fastest. It’s dated, and sets a dangerous precedent for eco-fascist ideas.

A year earlier in 2016, Disney – hoping to capitalise on the growing environmental consciousness – dropped the children’s animation Moana. Making nearly $500 million at the box office, directors John Musker and Ron Clements used imagery which captured elements of Pacific Islanders’ struggle against climate change, through a story where the protagonist struggled against the polluting of her island home.

However, Moana managed to overcome the environmental issues she faced by simply returning a stone to a magical island – and not by tackling the real root of the issues faced by Pacific Islanders: capitalism, exploitation and neo-colonialism. By doing this, global media superpower Disney exempt themselves from responsibility, obscuring human accountability and global inequality as well as reproducing classic gender stereotypes.

In doing so, Disney can maximise profit by ironically partnering with environmentally and socially destructive industries. Notably, they collaborated with Hawaiian airlines for three custom Moana-themed airbus A330s and built a resort in Hawaii criticised for exploiting the water supply of Native farmers.

Despite their successes, they have both reproduced a distinctly unhelpful environmentalism. One which environmental and climate justice movements have fought for decades. They present elements of environmentalism to the public and depoliticise them. It is damaging for marginalised communities, womxn and non-binary peoples, people of colour, and especially those from the Global South. At the same time, it is these people who are creating exciting and rebellious waves in environmental filmmaking.

When studying film and environmentalism, we became frustrated at how damn difficult it is to access independent films about nature that are produced, directed and filmed by womxn and non-binary people, particularly from marginalised communities. There is so much incredible stuff out there, and largely, the mainstream film industry is stagnant, white and male.

Now more than ever, there are inspiring, funny, cinematic, and devastating films that challenge the patriarchal and colonial foundations and aesthetics of environmental filmmaking. Nature is not separate from the human, nor is it ‘one immutable easily defined’ thing. It is so, so important that we all understand the value in platforming a diversity of opinions, experiences and movements and try to extend our viewing beyond what is handed to us on Netflix, Disney and Amazon.

This is why we started Lilith Archive, a platform which champions global womxn and non-binary filmmakers on nature, ecology and the climate crisis. Here are a few exciting films that challenge our thinking:

1) Apiyemiyekî? (2020) – Ana Vaz

Intimate and at times visually dizzying, Apiyemiyekî? documents the experiences of the Waimiri-Atroari, a people native to the Brazilian Amazon. Through uncovering an extraordinary archive of over 3000 drawings by the Waimiri-Atroari, collected by a Brazilian educator and Indigenous rights activist, the film acts as a space of reflection on the brutal Brazilian military dictatorship that spanned 1964-1985.

Illustrations are laid over footage of the Amazonas and the highways that now cut through it as a consequence of the government’s development project. We traverse landscapes from past and present, Ana Vaz unique film-making process explores collective memory and the trauma experienced by the Indigenous population and native lands in the name of development – asking us to question how the very concept of development is presented to us.

Available on Mubi. Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W-YZ82h1tRU

2) Ama San (2016) – Cláudia Varejão

Varejão’s patient study of the Ama, a community of Japanese freediving fisherwomen, is weirdly reminiscent of Wes Anderson’s Life Aquatic of Steve Zissou – except real. All dreamy pinks and blues, Ama-San follows the daily lives of these extraordinary women who fish for ocean products and pearl fishing on the sea bed without using oxygen tanks.

Varejão uses an unfiltered approach, mesmerising yet austere as we observe the women raising their kids, going for dinner, singing karaoke and then freediving to the bottom of the ocean like a daily chore. We hear through disjointed conversations how the ocean has changed for them, become less bountiful over their working lives. These subtle nods to the impacts of an overexploited environment show us how we are all affected in small ways, and why we should all care – a far cry from Hollywood’s fetishisation of climate disaster in films like The Day After Tomorrow (2004).

Available on Vimeo. Trailer: https://vimeo.com/ondemand/amasa

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

3) Grit (2018) – Sasha Friedlander, Cynthia Wade

At 6 years old, Dian and her family find themselves running from a tidal wave of toxic mud. Ten years later and studying to be a lawyer, she is demanding compensation from the drilling company that caused it. Evocatively shot, Grit is the lyrical story of a mother and her daughter mobilising against the corporation who’s exploitive endeavours cost them their home.

Following Dians metamorphosis into a bright, politicised young woman, we are introduced to a community whose homes and livelihoods are buried under sixty-foot of mud. As she takes on the pain of her elders, Dian fights for a better future for herself and her baby sister.

In an ode to their previous life, shots are long and drawn – lingering over a time that no longer exists. Grit is full of visual juxtapositions and demoralizing setbacks that make for difficult viewing at times. Yet, directors Friedlander and Wade manage to capture the spirited and inspirational community, who are refusing to become collateral damage at the hands of environmentally exploitative agencies.

Available on Vimeo. Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K1d6SECjibY

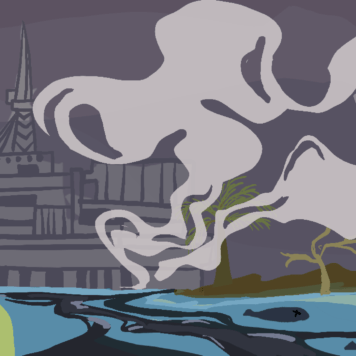

4) ENTROPIA (2019) – Flora Anna Bunda

Three women live in three parallel worlds. One traverses kaleidoscope forest-scapes, free from the constraints of modern society. Another patrols an endless supermarket, stuck in a cycle of consumption. The last is trapped in a simulation of perpetual motion, flanked by flocks of virtual birds. But when a fly causes a glitch in the system, the boundaries between these universes collapse and the women meet for the first time.

There is a lot you could take away from this vibrant, psychedelic, queer celebration of an animated short. Perhaps it is the many faces of one woman – a more primal self, a higher self and one in the plane we live in now, perpetually strolling the metaphorical corridors of a co-op. Aspects of ourselves we must learn to accept to live in peace and transcend the little barriers we make for ourselves. That we live in our world, but worlds live inside of us also.

Bunda’s animated dream-scapes are energising, give it a watch and let us know what you make of it. Not currently released, but catch it at Bitbang film festival, Giraf16 animation festival, La Truca festival and Cinanima festival.

5) Daisies (1966) – Vera Chytilová

A chaotic and savage commentary on nonsensicality of a life conditioned by capitalist excess and patriarchal norms. I swear we are not film snobs, but this piece of Czech surrealist cinema is a super fun watch. It’s one of those films which is super enjoyable, but almost more enjoyable when you google ‘what the hell was this about?’ afterwards.

Věra Chytilova’s iconic 60s masterpiece follows women in rebellion against conservative conventions placed upon them – “Everything is going bad in this world, so we’re going bad as well.” It addresses our relationship with nature in subtle ways, among other more prevalent themes. As the girl’s spiral into a blind carnival of excess they pin dead butterflies in boxes, hang leaf cuttings on walls, litter fruit on the floor – an ode to mindless consumption under capitalism.

Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cPpPpnVwRgY

Zoe Rasbash & Lois Barton of Lilith Archive