I recently spoke to Agri Ismaïl about his debut novel Hyper. It follows the lives of a Kurdish family throughout the Middle East, Europe, and United States.

Agri has creatively and unconventionally woven diverse themes and messages through the story of Rafiq, Xezal, Mohammed, Siver and Laika. What struck me the most is that this is not a dramatic journeys of migration story – he spares us the theatrics and utilises his characters’ inner worlds to tell us about the world of capitalism.

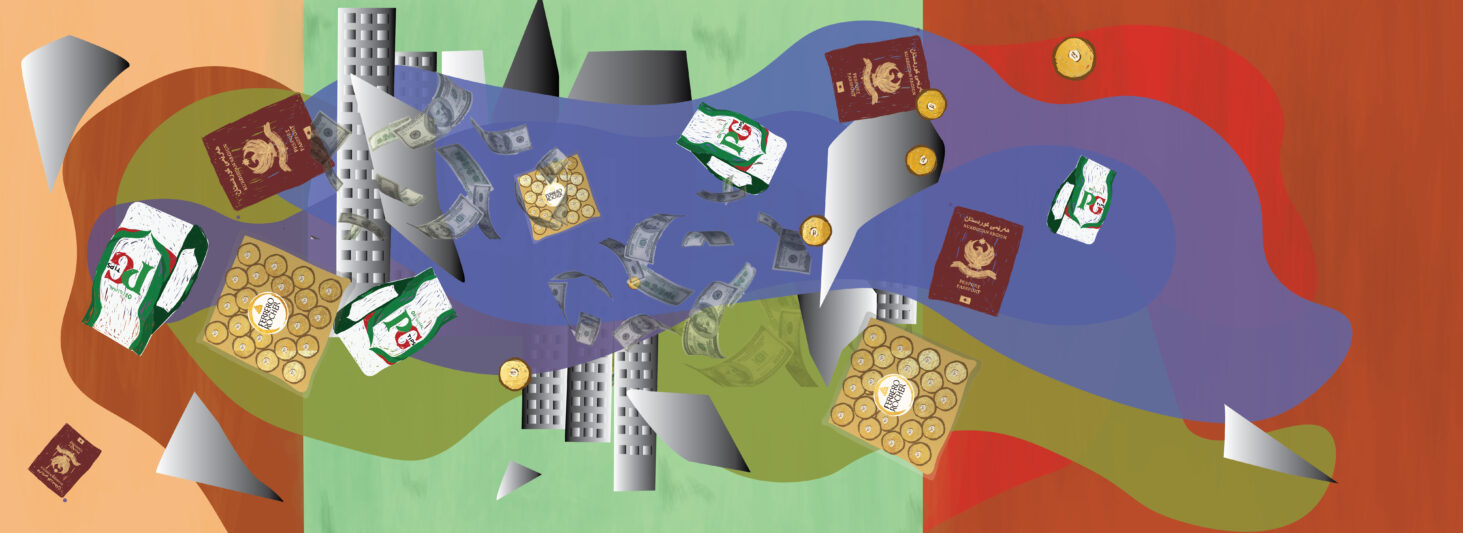

Agri and I, despite being strangers with divergent family backgrounds, find an unexpected connection in the shared anecdotes of Kurdish life in the world. It’s a subtle bond woven through the mundane joys of familiarities like status of a box of Ferrero Rocher, PG Tips, passport photos, unseen and unheard lives and the intricate dance with money – a layered, complicated, and often contradictory relationship we both navigate.

Money

The pages of Hyper serve as a mirror, reflecting not only the nuances of life in the West but also the intricate tapestry of Kurdish existence in our homeland.

In Britain, it’s considered improper to discuss matters of money socially, though money has been a constant factor when considering the legitimacy of asylum seekers, migrants and refugees.

Whether they are ‘really in need’ or ‘here to take our jobs and resources’ has dominated public debate for as long as I can remember – and those who can ‘safely’ go back to their countries are considered charlatans who don’t really need to be here.

Of course, the layered and often hard-arrived at decisions to leave their homes are not considered. Agri nods on the zoom call as I recount the tales my mother shared about her early days in London, fumbling with an unfamiliar currency in a foreign land, in which my mother would open her palms with a collection of coins when buying milk for her children, trusting that the shopkeeper would take the right amount.

I realise that during my travels, despite bouts of feeling out of place, my experience as an English speaker pales in comparison to the foreignness my parents encountered. This revelation resonates in the narratives within Hyper, serving as a poignant reminder of the gap between the generations in diaspora communities.

One of Hyper’s core themes is money. Agri’s perspective on the complex relationship between money, belonging and displacement is a testament to the rich and multifaceted nature of diaspora communities.

In our conversation, he contrasts his upbringings in Sweden and the UK. While summers in the UK provided a glimpse into a different diaspora, they also highlighted the distinctive nature of the Kurdish identity in London, intertwined with the city’s financial history and the challenge of being recognised amidst various minority groups.

The ordinary within the extraordinary

Agri draws parallels to Wandering Souls by Cecille Pin about the Vietnamese boat refugees in the ’80s to explain why London as the historic centre of capitalism and imperialism is an important landscape for many stories.

“I wanted to portray what it is to be a Kurdish family in a country that certainly has its own histories of colonialism and the consequences thereof,” he explains. “But even though Kurdistan is very much a consequence of British imperialism, it’s not seen as that: it’s seen as something else.”

Britain, along with the French divided Kurdistan into four nation-states, Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria. And for some reason most do not know this or understand the layers of oppression, suppression and assimilation this has meant for 100 years.

Perhaps statelessness or lack of recognition is what contributes, as Agri says too, to Kurdishness being lumped into larger cultural and religious identities. In addition to being a fantastic piece of fiction to read, Agri’s book is also educational and enlightening in its skillful portrayal of the mundane and the ordinary in the midst of migration stories often expected to be dramatic.

When talking to Agri, I’m struck by his creativity and ability to make connections that perhaps would not occur to most. He tells me that the book took so long to finish as he worked to avoid writing a typical migration novel, and the dehumanising risks of misery porn and self-exotification.

He says, “It’s ordinary people who, after kissing a girl and returning home all excited, find their parents amidst Barbie dolls and maps detailing various war zones. I aimed to capture how real-life suffering and conflicts seep into the ordinary routines of suburban life, blending seamlessly into the mundane.”

Perhaps to many, this isn’t ordinary at all – but to many migrant, and particularly Kurdish communities, this is the human and the ordinary amidst the impacts of capitalism. I couldn’t agree more when Agri explained, “So, I was thinking it had to be a Kurdish family. I mean, when you really want to highlight the harsh realities of capitalism, what better way than portraying a family without a home, no recognised land, and no nationality or passport, right? That sense of being stateless was crucial to what I wanted to convey.”

How to write the unwritable

I appreciate Agri’s decision to avoid turning the roots of the family’s journey to London into a dramatic focal point. Instead, the narrative briefly mentions their journey from Tehran to Baghdad and then to London in one paragraph.

This choice allows for a deeper exploration of the characters and their complexities. For example, it’s interesting to read Xezal’s – the wife of a revolutionary and mother who is burdened with the lifemaking of her family – bitterness and complex emotions. I saw a familiarity in her struggles, especially later in life, and noted the nuance of her relationship with her children, acknowledging both the bitterness and occasional dislike that adds layers to her character. Agri’s ability to capture the mundane, the complex, and the familiar in the characters’ lives stands out as a unique, authentic and quite funny representation of Kurdish experiences.

What I also found impressive is how the parents, representative of political ideologies, navigate their individual paths. The father, Rafiq, steeped in communist ideals, embodies a commitment to big ideas while grappling with personal and inter-personal failings. The mother Xezal, on the other hand, finds these ideas suffocating as she never sees them translated into their own lives. She faces their bitter reality with resilience, showcasing the two archetypes of older generations – those who check out and those who power through with bitterness.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

I can only imagine how many readers of Hyper will relate to this portrayal of communism, echoing the classic era where grand ideas often overshadowed self-reflection and personal application. We see the nuances of Rafiq’s intimate life, with the contradiction between his political ideals and the way he navigates family dynamics.

To me, putting too much emphasis on fighting outside foes without focusing on changing ourselves is a common trait in certain types of political organising. Hyper gracefully goes between the serious and the humorous, painting a rich tapestry of the Kurdish experience in the intricate dance of migration, belonging, and family dynamics. Agri infuses what is in essence a bleak, lonely and collapsed family unit with entertainment and humour – a familiar coping mechanism of communities in struggle. Somehow he does that while detailing subjects like high-frequency trading and migration patterns.

Migrant currency

The book is filled with subtle details, such as obtaining a passport photo in Iraq (a scenario where personal features and passport regulations often take a backseat to the photographer’s artistic expression), and the universal experience of gifting a box of Ferrero Rocher. In a 2018 article, journalist Liana Aghajanian wrote about the cultural status and symbolism attached to the gold-wrapped chocolates, and how it became a unique form of communal currency, passed from one house to the next but never opened.

The dialogue continues as we explore the quirky familiarity of other references in the book, like the reverence for PG Tips in Kurdish households. In the book, when the mother Xezal moves back to Kurdistan she says, “This is it” as she sips on a cup of the pyramid shaped tea bag brew. The act of bringing back English tea to Kurdistan becomes a symbolic gesture, highlighting the arbitrary cultural significance attached to certain products.

It was a pleasure to talk to Agri, as our conversation seamlessly weaves between personal anecdotes, cultural reflections, and the broader diasporic experience. The narrative captures the complexities of identity, humour, and shared customs within the Kurdish community, creating a rich tapestry that invites readers into the unique world Agri has crafted.

Our stories

His decision to frame the story within the context of Kurdish diaspora emerged organically. The dispersed nature of Kurdish communities worldwide provided a fitting backdrop for characters navigating the intricacies of the 2008 financial meltdown. Agri aimed to transcend an individual or familial focus, opting for a broader exploration of the global impact.

I was curious how much of Agri’s own life was written in Hyper. He tells me: “In terms of the biography aspect, it’s a bit challenging. The characters had to be made up because I needed them to do certain things to drive the plot. So they’re not based on real people. However, all the small details are authentic, even though the lives created to illustrate them are not.” The novel thus became a composite of truth and imagination, a reflection of the author’s observations of the minutiae of the Kurdish experience.

Unknown lives

In the book we discover Rafiq’s unfinished memoirs, a poignant symbol of unfulfilled revolutionary aspirations. It reminded me of the abundance of former revolutionaries in London, living anonymous lives, often living unrecognised as a taxi driver. This was demonstrated through the contrast between Rafiq’s popular farewell in Sulaymaniyah and his anonymous existence in London.

Agri agrees and adds that this is also the case in Sweden, where revolutionaries often find themselves caught in the dichotomy of pursuing ideals and the practicalities of earning a living. He explains, “Similarly in Sweden, we observe many individuals who arrive as revolutionaries in their home countries. The reality is that they must secure a living to sustain themselves, often resorting to menial jobs due to the lack of recognition of their qualifications. Language barriers further hinder their acceptance into broader society. This dynamic is a common aspect of migration, not only in Sweden but also in cities like London and other European urban centres. While these people may initially be granted refugee status based on their political circumstances, this recognition often marks the end of their identity as political refugees, as they are expected and sometimes forced to assimilate and conform to their new surroundings.” For so many, this erasure leaves a void, an unspoken loss that complicates the sense of self.

As the conversation deepens, Agri delves into the second generation’s struggle to reconcile their lived reality with our parents’ narrative of displacement. He reminds me that, “Then there’s the second generation, grappling with the question: “How do I find my way in this?” This is the only home we’ve ever known, yet everything, including our parents, suggests otherwise. It’s a struggle between the reality we’ve experienced and the identity we’ve internalised.”

Within the pages of Agri’s novel, two compelling themes intertwine: the persistent yearning for roots and the simultaneous rootlessness that characterises the experiences of its protagonists. This exploration delves into the mosaic of collective identity and the paradoxical collapse of the family unit that often goes unnoticed. As I navigate through the narrative, I find myself both defending and questioning the traditional family unit, a dichotomy that challenges my political beliefs.

A return to the homeland

The novel’s final section evokes a poignant moment as the desert transforms into mountains during their drive to their hometown Sulaymaniyah. This symbolic journey offers the characters a profound connection to their homeland, prompting reflection on the nature of this newfound link to their roots. Is it a genuine reconnection, or does it merely embody the bittersweet beauty often found in the concluding moments of a story?

Agri’s contemplation on the novel’s conclusion sheds light on the delicate balance between sentimentality and cynicism. The risk of embracing sentimentality, after pages steeped in cynicism, leads to a nuanced ending that offers both hope and melancholy. The temporal placement of this moment before the tragic fates of the main characters adds layers to its significance, capturing a fleeting connection amid the prevailing isolation depicted throughout the novel.

The narrative extends beyond the personal, exploring the collapse of family units and the societal expectations that persist despite evident fractures. The paradox of self-isolation as a coping mechanism comes to the forefront, revealing the fundamental loneliness that remains unresolved.

In contemplating the novel’s broader themes, the exploration of our ways of relating to one another emerges as a profound takeaway. While the grand questions of changing the world persist, the narrative invites readers to introspectively examine connections with ourselves, those around us and the world as a whole.

As characters navigate their own paths, the underlying question lingers: does life offer more than simply getting by?

What can you do?

Read

- The Kurdish Women’s Movement by Dilar Dirik

- The Purple Color of Kurdish Politics Women Politicians Write from Prison Edited by Gültan Kışanak

- Hevaltî – Revolutionary friendship as radical care

- An End to the Darkness by Rosa Burc

- More shado coverage of anti-capitalism

- Zan, Zendegee, Āzādee: the women at the sharp end of resistance in Iran

Watch

- The Kurdish Women’s Movement: History, Theory, Practice | Dilar Dirik, Elif Sarican

- Komîna Fîlm a Rojava – The Rojava Film Commune is a collective based in Rojava, West-Kurdistan, in northern Syria.

- David Graeber: Why Rojava Matters

Listen

- Song: Hunergeha Welat – Şervano

- Song: Awazê Çiya- SARA

- Pomegranate Podcast: Pomegranate Podcast (@pomegranatepod) • Instagram photos and videos

Support