Lush has been an eco-conscious stalwart of the British high street since the mid-nineties, pioneering the No Animal Testing movement through boldly-coloured, heavily-scented products – but its impact far exceeds their cruelty-free bath bombs. Lush represents brand eco-activism at its finest, and their closure of all Lush shops (including the online store) in solidarity with the Youth Climate March in September proved they put their money where their mouth is. shado went to Poole to speak to Rowena Bird, one of Lush’s six co-founders, to find out more about the work they are doing. Sat in her lab above the original shop on Poole’s old high street, we talked about the problems of packaging, the importance of supply chain and brand accountability and the interconnectedness of the environment, eco-systems and the products we put on our skin.

What are some of the main problems that you think exist within the beauty and cosmetics industry and what are some of the changes that Lush have always pioneered?

Packaging is the biggest problem that we have. I did a beach clean in Manila, in the Philippines, and we kept all the cosmetic packaging to the side. We lined it all up, and the amount of waste was so shocking. Sachets are my biggest bug bear. I can however see the need for them, though – so the conversation needs to be how we replace them.

But I guess that’s the thing, it’s so important to be coming up with alternatives rather than believing you can simply stop things overnight.

Well, you couldn’t stop it in a lot of countries, where many live below the poverty line. In parts of India, for example, if you’re just taking home a few rupees for your wages and a bottle of shampoo costs you more than that, you simply can’t afford a bottle of shampoo. That’s a luxury. Even though, if you added up how many sachets you’d need to fill a bottle, it would be well worth you buying a bottle – but if you haven’t got the money for that initial down-payment, you can’t do it. But of course you can’t ban sachets outright, because then you’ve priced people out of cleaning their hair. It’s about understanding there’s a need for small and affordable sizes, but thinking how it can be replaced by something that won’t get washed straight into the ocean.

A great example of the importance of an approach which looks to solutions is Avroz Shah, who did the big clean up on Versova beach. It took him 4 and a half years to get that beach back to being a beach. A big part of his process was including and engaging with the people who lived in the areas nearby. They had showers and toilets, but these weren’t in a usable state – so people were preferring to use the beach. So, Avroz started talking to local communities and started with cleaning the toilets and showers, so that people wanted to go in there. Immediately, you’ve removed that waste from the beach.

It’s not about going in and saying ‘don’t do that’ – that’s the Ivory Tower mentality which is so problematic. Instead, you need to find out what is needed on the ground and then try to find a solution .

So, back to sachets – we know that people can’t afford that, so the question needs to be can we make mini shampoo bars and sell it for the same price as a sachet? Is there any way we can make something that’s solid so it doesn’t need packaging? This is what we should be looking at.

Talking more specifically about the beauty industry, I was really determined that, as much as possible, we would reduce the packaging within the Lush makeup range. We’ve got our reusable vintage-look aluminium and brass lipstick holders, which are push-up instead of twist. With all of this, it’s about giving the products enough of a change that it makes an impact, but still leaving it recognisable – because you can’t be too wacky. If i just sold all the lipstick refills without the case, it would be too much. You wouldn’t be able to put it in your makeup bag; it wouldn’t be transportable… and that’s a reason not to buy it. Of course, you also have the choice of putting the refills in some packaging you already have. I’m trying to make it flexible so you can be as environmentally friendly as you want. You have to still give people agency over their decisions.

The Tagua nut is the next phase for our packaging to create eyeshadow palettes. The Tagua is a palm, but you can’t regrow it – so you can’t take one of the nuts off the tree and plant it and then grow another Tagua tree. Once those trees are gone, they are gone – and we’re headed in that direction. But the Tagua flower (on the male palm) hosts 6 or 7 different ecologies, and then insects take these to fertilise the female tree and the nut forms on there. You don’t harvest those until they drop to the floor, by which point they are like a lump of vegetable ivory – and that is what we are using. It was a big thing years ago because the Tagua nut replaced ivory in button making, and then plastic came in and replaced the Tagua nut. So as the industry started to go down, the trees started to get cut away – which is why we’re on the verge of losing the species. But by us making the packaging out of the nut, we hope it will again become a big thing, and eradicate the risk of extinction.

What are some of the stories you are most excited about sharing?

Our Cork Pots. The cork industry is in a bit of turmoil, because the wine industry is reducing its use of cork, moving towards plastic ones and screw tops. The thing about cork trees is that they absorb more carbon then they give out – they’re better than carbon neutral, they are actually in a deficit. So, supporting the cork industry means that the trees continue to grow – and it’s really important to keep those cork forests.

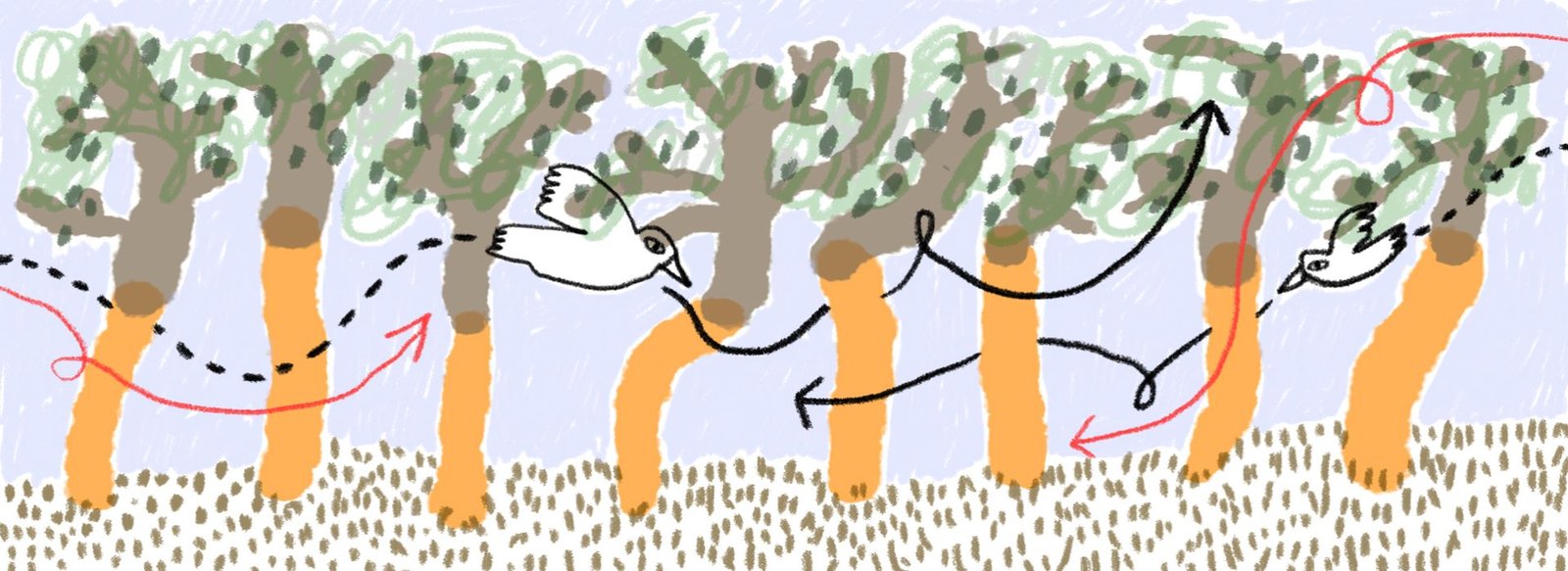

We get the cork from Portugal, which is also where we get our salt. There are salt pans there which are part of the migratory routes for birds. Birds travel in different routes all around the world, but their stopping routes are becoming fewer and further between, where people are devastating the land that they would normally stop and feed on. And of course, if you do that they can’t stop and feed and rest and then they die because they can’t re-energise themselves for the next part of the journey. So, we want to keep the salt pans in use so we maintain this stop on the migratory journey.

The Portugese salt and cork are just two beautiful products. We then found these two guys doing sail-boat deliveries and asked if they wanted to do a delivery to us in Poole from Portugal. And they said yes! They picked up our cork ports and our salt, then they picked up olives for somebody else, and then they sailed in. Seeing them sail into Poole harbour, with these huge red sails at full mast and a Lush flag atop – it’s one of those things that makes you get up and want to come into work everyday. To make something like that happen, it makes you think: what can I make happen next?

See more of Lauren’s work on instagram here and her website here

Interview by Hannah Robathan and Isabella Pearce, co-founders of shado