It’s been over a year since Sarah Everard’s murder by a serving police officer and the police force that employed him launched a violent crackdown on the Clapham Common vigil held in her name.

In the wake of this growing political crisis for British policing, more people are arguing against carceral feminist responses to gendered violence, instead favouring abolitionist feminist alternatives.

But what are the differences between carceral feminism and abolition feminism?

What is Carceral Feminism?

The term ‘carceral feminism’ was coined by sociologist Elizabeth Bernstein and refers to a branch of feminism that seeks to address gendered violence by investing in police and prisons.

Whilst prisons and policing are currently the dominant, mainstream response to gendered violence, this was not always the case. The modern feminist anti-violence movement that rose up to confront domestic and sexual violence came about in the context of revolutionary movements in the 1970s.

Feminists squatted empty buildings to establish refuges for abuse survivors and resisted patriarchal power relations by running them collectively on the principles on consensus decision making and mutual aid.

Many feminist groups saw the police and state as being the foundation for patriarchal violence in the home and therefore invested in other remedies such as campaigns for benefits and housing for survivors as well as education to prevent abusive relationships.

However, the fallout from the global financial crisis hit many radical movements hard and many refuges sought state funding to sustain themselves.

This usually involved compromising on their radical values by implementing clear management structures with hierarchical distinctions between survivors on the one hand and workers and managers on the other.

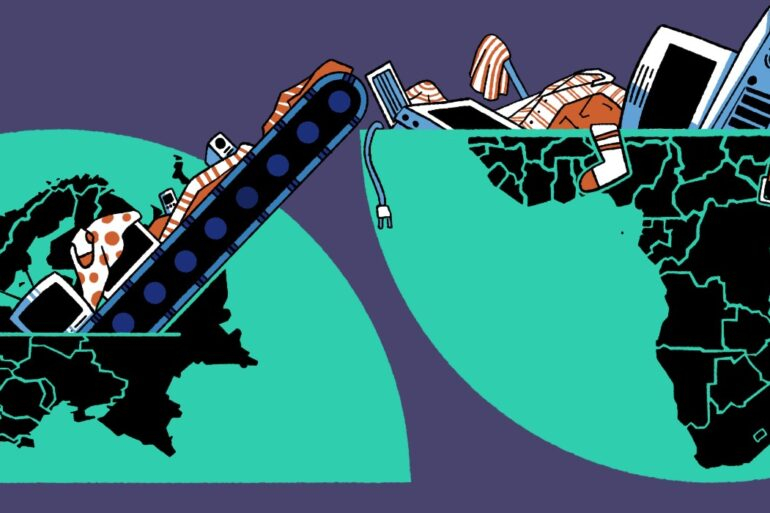

Since the 1980s, the state has gradually withdrawn funding from community-based responses to gendered violence, instead favouring a law-and-order approach.

The services advocating for police and prison-based responses were more likely to be funded, and the more critical organisations were incentivised to follow suit or risk closure.

Why further policing can cause more harm

Carceral feminist policies on gendered violence tend to focus on increasing the number of arrests and prosecutions as well as longer prison sentences for those convicted. Carceral feminists argue that removing the perpetrator from the situation and locking them up will protect survivors and end the abuse.

However, measures that were brought in to protect women from violence saw more women arrested than ever.

Survivors are often arrested instead of or alongside their perpetrator for physically defending themselves. Further, survivors of abuse often do not behave like the ‘ideal victims’ expected of the criminal justice system. In reality, the distinction between ‘survivor’ and ‘perpetrator’ is often not clear cut.

Additionally, increasing the presence of police in the lives of survivors has led to many being criminalised for other matters such as sex work, involvement in the drug trade or immigration enforcement.

Disproportionate impacts on communities of colour

Over half of police forces in England and Wales have a policy of arresting those reporting domestic or sexual violence where they are suspected of having insecure immigration.

Gendered violence occurs across all classes and races. However, some are far more likely to face a carceral response to harm perpetrated in their community. Indeed, police departments have cynically used the additional powers associated with domestic and sexual violence policies to further criminalise poor communities of colour.

In the 1980s Black communities responded to extreme levels of police harassment and violence with uprisings or ‘riots’.

In 1985, Brixton and Tottenham saw some of the biggest disturbances and not long after, the first domestic violence units were established in these areas. Some interpreted this as a cynical attempt to criminalise Black communities as revenge for resisting police repression.

Police misogyny

Since Sarah Everard’s murder, a string of media reports have shone a light on the long standing – though little acknowledged – problem of police misogyny. Research has found that police officers who abuse their partners are a third less likely to face conviction than the general public.

Recent reports also found that the most common form of police corruption is the use of position for sexual gain.

Since 2010, 750 Metropolitan police officers have been accused of sexual misconduct with only 83 being sacked. The groups that police officers are most likely to target for sexual abuse were domestic and sexual violence victims, sex workers and drug users.

The police use coercive and controlling behaviour as part of their job. They have the power to stop, detain and strip search people with a vast array of arsenal to ensure compliance, from batons and tasers to pepper spray and guns. Police officers use both authorised and unauthorised violence as part of their day job, and this includes gendered violence.

What is Abolition Feminism?

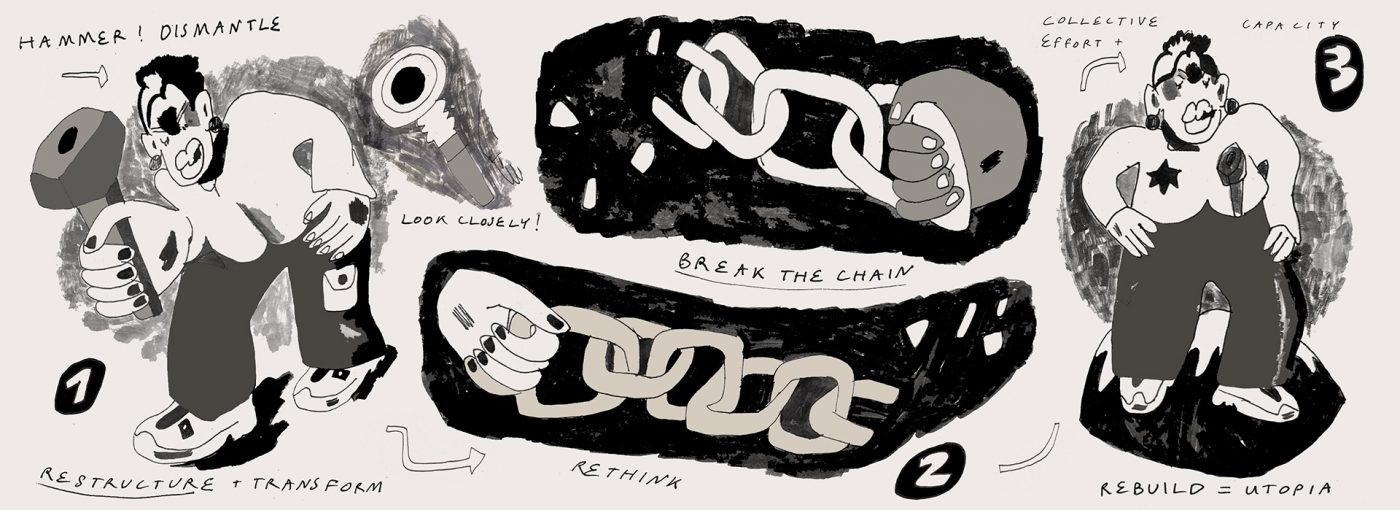

Abolition feminism argues that police and prisons should be dismantled whilst also seeking alternative ways to address gendered harm in our communities.

Recognising that relying on state coercion to address harm in our communities only perpetuates violence, abolition feminism instead invests in community-based responses and transformative justice.

Transformative justice

Transformative justice is both reactive in the sense of developing tools to respond to harm when it has happened, but it is also preventative in that it identifies and addresses the causes of harm so that it is not repeated.

When harm has occurred, transformative justice approaches seek to identify the conditions that make harm more likely such as homelessness, poverty and the cultural normalisation of unequal power in relationships. One way of preventing harm would be to invest in education that focuses on how to engage in healthy sex and relationships, emphasising mutual respect and consent.

Further, communities can create their own emergency responses that both support survivors whilst recognising that it is our collective responsibility to support our friends, family members and neighbours to change when they have perpetrated harm. The Bay Transformative Justice Collective uses pod mapping exercises as the starting point for reorganising communities in a way that responds effectively to abuse without calling the police.

One year after Sarah Everard and British policing remains in crisis. We are faced with the opportunity to reimagine a world without police and prisons and instead increase our collective capacity to rebuild our communities to respond to our needs and address harm at the root.

What can you do?

- Pre-order Abolition Revolution by Aviah Day and Shanice McBean

- Read Me, Not You The Trouble with Mainstream Feminism by Alison Phipps

- You can also find a range of blog posts, reading groups and videos on abolition and carceral feminism on the Abolitionist Futures website

- Donate to Sisters Uncut HERE

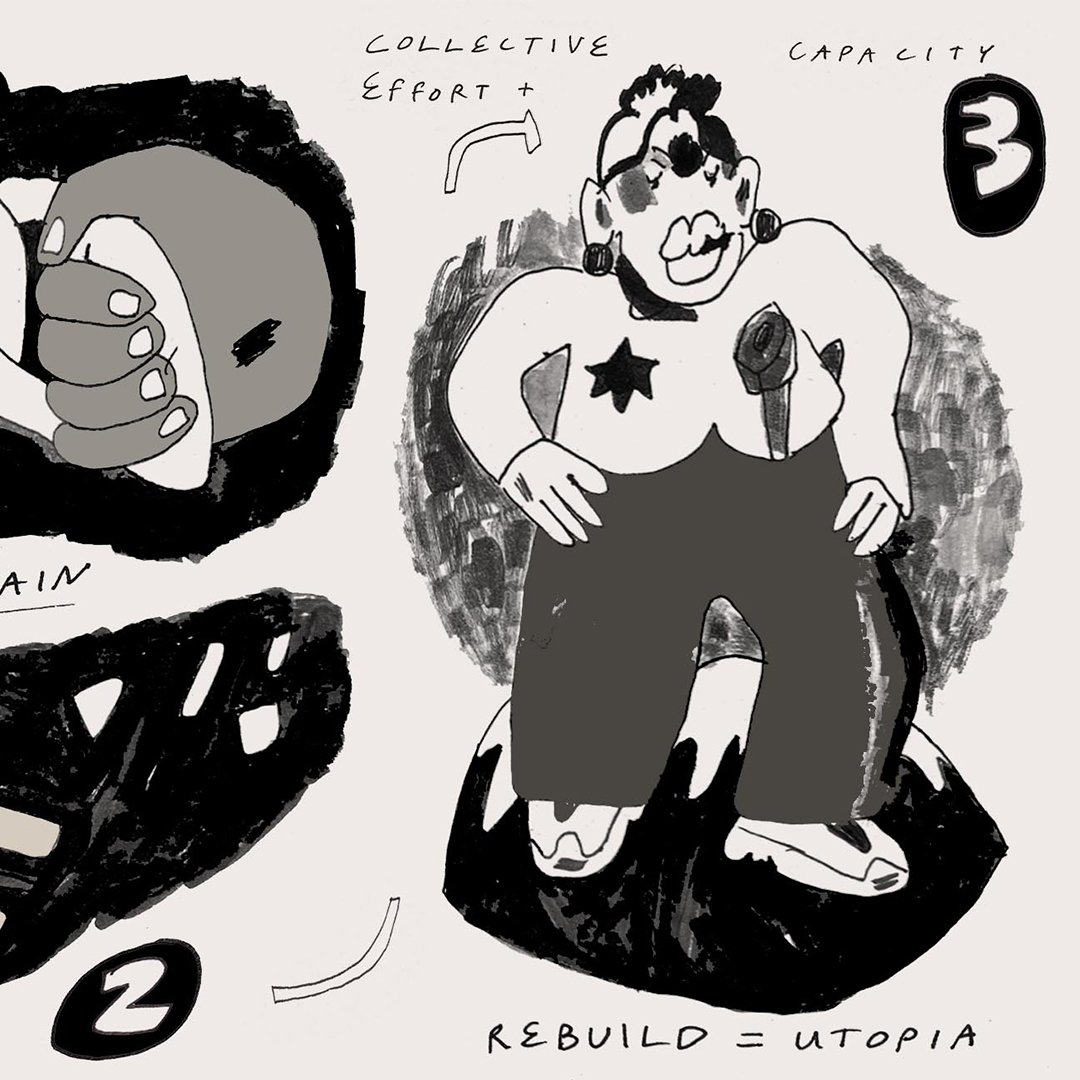

Luci says, “For this piece I was thinking of ways of simplifying what abolition means visually and the things that cropped up were the idea of breaking, looking and thinking. I was thinking about this sequentially, envisioning (in a silly and naive way) what the steps would look like towards abolition if you were to put it in an instruction manual that could be read and understood by anyone.”