Seeking asylum in the Age of Offshoring

Shrinking space for human rights protection in London, Copenhagen and Berlin

Only a few years ago, offshore immigration policies – the idea of shifting the responsibility of processing asylum claims to a different country – were considered an idea only palatable among the populist far right.

Now, on the brink of unfolding climate emergency and in the midst of a war at Europe’s border, countries are recanting their obligations under international human rights law and pushing for policies that take people who seek asylum out of sight and over the border. In this context, shado mag and Unbias the News present a collaborative investigative series into how these policies are affecting activists and communities that stand for freedom of movement and the right to refuge.

Across Europe, people whose asylum claim has been rejected are forced underground to avoid being deported. That means living ‘outside the system’ – relying on help from friends and family to get by, as well as EU agreements that grant access to housing assistance and healthcare to all in need.

Through a series of repressive measures aiming to discourage migrants from staying in Denmark, the country bars “underground” asylum seekers from getting help, criminalises aid and deliberately makes their lives more difficult – violating international human rights protocols as a result.

Michael’s story

When 30-year-old Michael had his asylum application rejected, he felt he had no choice but to go underground to avoid being deported. “I was so afraid,” he says. “I thought, what is going to happen when I get sent back?”

Although people go underground all across Europe to avoid deportation once their asylum claims have been rejected, communities face a particular set of hardships across Denmark. Through in-depth investigation, it has become clear that Denmark is deliberately infringing on the human rights of people whose asylum has been rejected.

In 2015, Michael was finishing his business degree at university and leading an LGBTQI+ activist group in Uganda, where homosexuality has been criminalised to varying degrees since the 19th century. Once the authorities discovered the group, he got kicked out of university, and most of his fellow activists were arrested.

Fearing the fate in store for him, Michael decided to flee. After a journey from Uganda through Sudan, Libya and on a dinghy boat across the Mediterranean, he arrived in Greece. The Red Cross accompanied Michael to Germany, and he continued on to Denmark. There, he applied for asylum, learning Danish as he waited for a decision to be made.

The struggle for LGBTQI+ asylum in Denmark

In many ways, Denmark is a pioneer in protecting LGBTQI+ rights. In 1989, it was the first country in the world to legalise gay marriage. In 2014, it became the first European country to allow trans people to affirm their gender – no medical expert approval needed. Today, Denmark is ranked the third most LGBTQI+-friendly country in the EU.

This progressive track record should extend to the asylum system. On paper, LGBTQI+ people seeking asylum in Denmark are legally entitled to protection if they are persecuted because of their sexual orientation. But according to Danish NGO LGBT+ Asylum, obtaining asylum on these grounds is anything but simple.

The NGO found that when Danish immigration officials assess credibility through interviews, they pose questions that are invasive, stereotypical – and often insensitive to cultural barriers that hinder applicants from discussing sexual orientation openly.

However, authorities also assess an asylum claim based on available data about the applicant’s origin country. By 2015 (the year that Michael applied for asylum), the Danish Refugee Appeals Board already had access to credible knowledge showcasing that LGBTQI+ people in Uganda face persecution. But the answer he finally received in 2017 did not reflect this.

“My asylum claim was denied, even though I had told the authorities about my sexual orientation and my activism in Uganda in multiple interviews,” he says. “They said that because other LGBTQI+ people live in Uganda, it’s safe to return to.”

Over the past five years, the number of people seeking asylum who have been granted residence permits has fluctuated, ranging from about a 31-66% approval rate per year. While these numbers are relatively in line with other European countries, the percentage is much lower for newcomers to the country compared to residence permit holders who later applied for asylum.

In 2021, UNHCR urged Denmark to reform its asylum system, stating that it is ‘concerned with the pace and scope of the restrictions introduced over the years to restrict asylum space’.

Meanwhile, the deportation rate is rising: in 2020, 18.5% of rejected asylum seekers meant to be deported were sent out of the country, but by 2022, that percentage climbed to 40.5%.

Life underground in Copenhagen

When Michael’s application for asylum was rejected in 2017, he went underground. Between 2016-2019, 3,593 rejected asylum seekers had disappeared from the system and were wanted by the police as a result.

During the three months he spent underground in Denmark, Michael moved between friends’ apartments. Yet even leaving the house would give him intense anxiety. “That year, I read about new policies which terrified me. I felt like I shouldn’t even risk going outside,” he says.

In 2017, the Danish government outlawed begging and homeless camps that create ‘insecurity’ in public spaces, punishable by a fine, jail time or deportation. According to the bill itself, these laws are meant to act against ‘foreign visitors’ who camp in public spaces – and in an interview, Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen said that ‘it is completely intolerable that the zoning ban affects Danish homeless people’. Documents accessed for this investigation outline that between 2017 and 2021, foreigners were charged for violating the begging law 98% more often than Danes.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

While the sources I spoke to for this story attest that these laws are primarily enforced against the Roma community, this did not make a difference to Michael. “I knew there were places I should avoid during the day, because every minute and at every corner, I could see the police,” he explains. “Going to bars; train stations; clubs; all of that was out of the question.”

In 2021, the Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights of the United Nations (OHCHR) called on Denmark to repeal its provisions criminalising poverty – especially the begging law. It didn’t.

Aid for all – unless you’re a migrant

Michael sometimes felt guilty staying at his friends’ apartments for too long. But finding a bed at a shelter wasn’t a stable option. “It’s very, very difficult to stay at a shelter if you don’t have papers,” he says.

According to the Danish Social Services Act, state-funded shelters cannot admit people unless they are registered as Danish residents. But Maja Løvbjerg Hansen, a lawyer at Stenbroens Jurister who aids street-based people, says that the rhetoric inside the country is the problem more than the legislation.

“I’ve experienced social workers telling me they don’t know if they can help people without ‘social rights’,” she says. “The term sounds good – but as a lawyer, I don’t know what it means. There are many different legislations, and almost all of them have emergency paragraphs that you can aid anybody by. But Danes have been conditioned to believe that migrants are not to be helped,” she says.

From 1970-2016, Danish media overwhelmingly presented negative views about immigration – often depicting immigrants as threats. In 2019, Danish newspaper Politiken ran an article stating that most underground asylum seekers in Denmark go ‘asylum-shopping’; meaning, they leave the country to wait 18 months before they can come back to Denmark to apply for asylum again, which is possible according to the Dublin Regulation. In response, the Minister of Immigration at the time, Mattias Tesfaye, used the term ‘asylum-shopping’ in parliament, stating that it must be stopped.

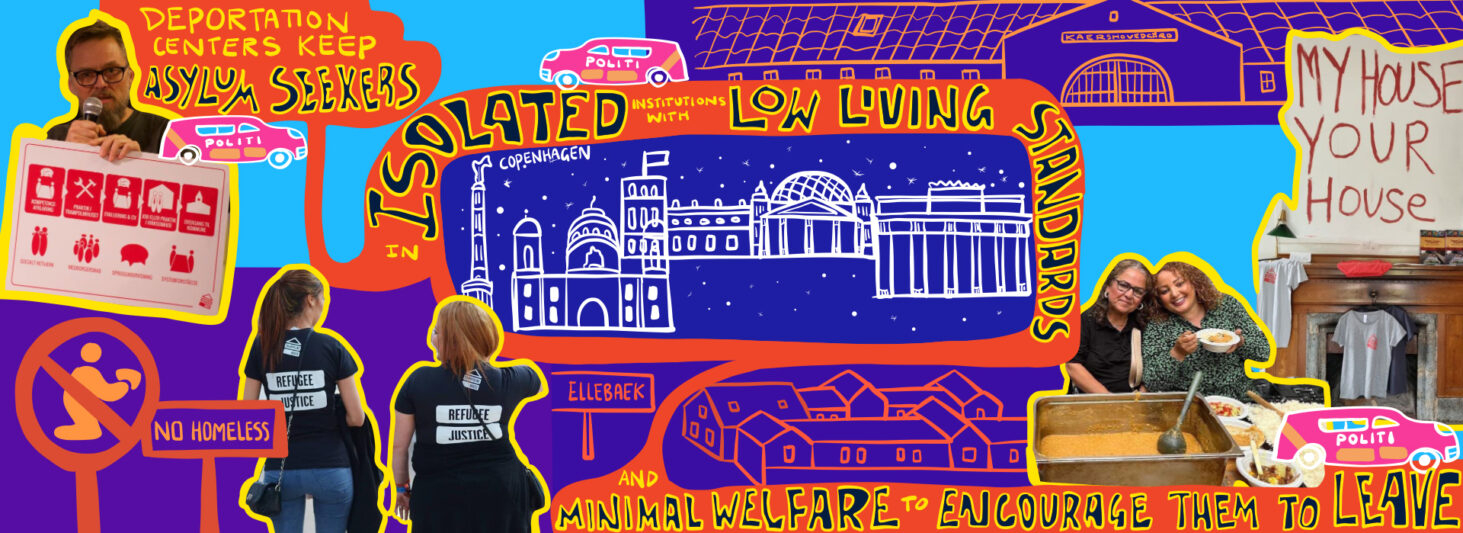

But in contrast to the findings from the Politiken article, 10 people I spoke with for this story say that when people go underground, the intention is not to return to Denmark. One of them is Nabila Saidi, the co-founder of activist NGO Trampoline House. She says that in the NGO and activist community, it’s well known that people whose claims have been rejected have better chances of living decent lives outside of Denmark. ‘People in the community advise them to go to other countries,’ she says.

An immigration centre ‘not suitable for humans’

Eventually, Michael was intercepted by Danish authorities. They sent him to Ellebaek – an Immigration Center that detains people who have had their asylum claims rejected and who, in the eyes of the state, aren’t cooperating with Denmark’s decision to deport them. There, he spent 13 months.

“Ellebaek is a prison, even if they don’t call it that,” he says. In 2020, the Centre of Europe’s Anti-Torture Committee published a report outlining conclusions from their visit to Ellebaek. The report said that Ellebaek’s detained migrants were subjected to excessive force and racism; restricted access to open air, sometimes even to 30 minutes a day; denied access to mobile phones, punished by 15 days of solitary confinement; and placed naked in observation rooms if found to be at risk of suicide.

Hans Wolff, the Anti-Torture Committee delegation’s leader, described Ellebaek as a place ‘not suitable for humans’. He even threatened to take legal action against Denmark in the European Court of Human Rights unless the country implemented the Committee’s recommendations within three months.

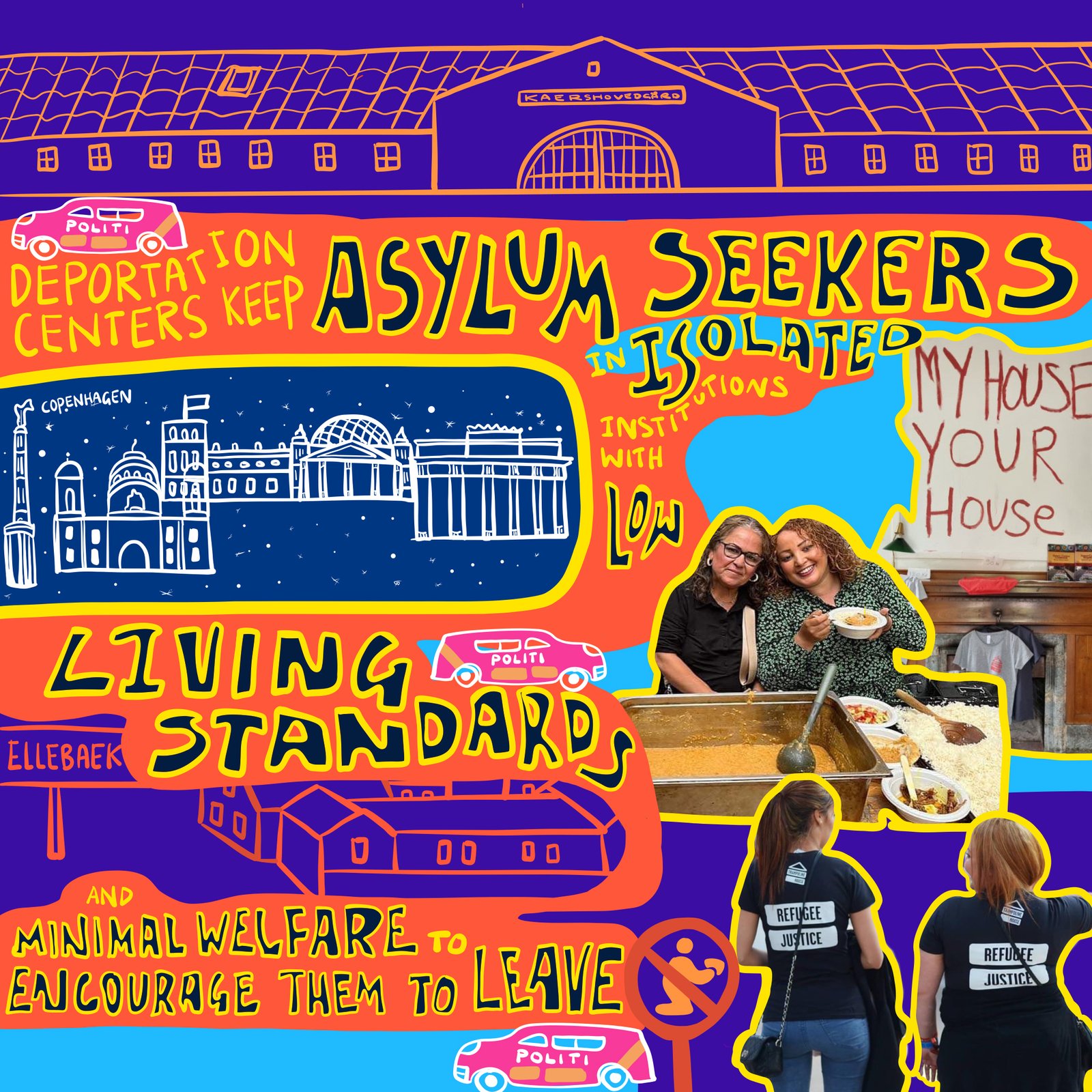

Yet in response to the report, the Justice Minister at the time, Nick Hækkerup, said that Ellebaek is a deliberately hostile place. Since 1997, ‘motivation enhancement measures’ have been enshrined in the Danish Aliens Act – outlining that deportation centres should keep asylum seekers in isolated institutions with low living standards and minimal welfare to encourage them to leave.

In 2019, a man kept in Ellebaek took his own life. Michael knew him. “His name was Tesfai, and he was my neighbour,” Michael says. In between 2012 and 2018, two suicides and six suicide attempts at Ellebaek were recorded.

For Michael, Tesfai’s suicide was the breaking point. “I decided that I needed to leave Denmark, rather than be sent from detention centre to detention centre,” he says. He agreed to deportation and was sent to Kærshovedgård departure centre while waiting for the authorities to process his papers. But shortly after arriving there, he fled to Copenhagen’s streets again. It felt safer than being inside this institution.

“The situation at Kærshovedgård is very alarming. People are treated like they’re in prison,” he says. In 2017, multiple human rights organisations assessed that the conditions at Kærshovedgård amounted to an ‘illegal deprivation of liberty’.

In October 2022, Michael was finally deported back to Uganda. Since then, he has lived what he calls a ‘silent life.’

“You can’t open up to people, you need to move around a lot – and you definitely can’t mix with groups of LGBTQI+ people. You can be arrested anytime,” he says. In May 2023, Uganda passed one of the toughest anti-LGBTQI+ bills in the world: now, homosexuality can be punished with life in prison – or even the death penalty.

But if he had to do everything all over again, Michael would never have tried to go to Europe in the first place. “I don’t even want to imagine that I’d have to live through a situation like that again,” he says. “I’ve seen how undocumented people are treated in Europe. It’s bad, and especially bad in Denmark. So, I’d rather see how life goes here. I still have hope for my future.”

‘Zero asylum seekers’ at the cost of human rights

Deporting rejected asylum seekers is complicated. They need to agree to be deported; their home countries may not agree to receive them; and many go underground to avoid deportation and become untraceable. Moreover, EU courts have occasionally ruled that handing a rejected asylum seeker over to the first European country where they had their case processed is not possible if returning there puts them at risk.

However, Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen has said that Denmark’s goal is to have zero asylum seekers. Since Denmark cannot stop people from seeking asylum within its territory due to its international obligations, or deport people as quickly as it would like to, it is turning to other tactics.

The 2017 laws outlawing begging and homeless camps squeeze migrants off the streets – and can lead to deportation. Shelters are barred from offering undocumented migrants places to sleep, and grassroots organisations are left with little means of offering aid. Asylum centres are deliberately awful to motivate people to leave the country. In a climate marked by politicians worrying about ‘asylum-shopping’, these measures systematically infringe on migrants’ human rights to push them out – and send a message to potential asylum seekers that they are not welcome.

Mette Frederiksen says that Denmark is a reliable international partner. Yet the state shrugs off mounting criticism from international human rights watchdogs, and its own partners like the UN. She insists that Denmark fights for human rights. But in reality, Denmark makes life as difficult as possible for people seeking safety inside its borders – overtly violating their human rights in the process.

This article was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe, www.journalismfund.eu

What can you do?

- Donate to Trampoline House

- Donate to LGBT Asylum

- Read more about Denmark’s turn against migration in this article

- Sign Amnesty Denmark’s petition calling to stop Danish police discrimination

- Watch Al Jazeera’s video ‘Why is Denmark Taking a Hard Line on Migrants and Refugees?’

- Donate to Danish advocacy group Refugees Welcome

- Donate to Together We Push, a grassroots organisation supporting people in Denmark’s deportation centres (use their email in a PayPal donation)

- Read: Demonising migrants, fortifying borders: Germany’s downward asylum spiral

- Read: The floating prison and uncharted waters of UK offshore immigration detention