“All that’s left is pain management, I’m afraid”. I blink back tears as the doctor tells me this, although I’m not surprised.

The story is the same for pretty much anyone who is diagnosed with interstitial cystitis (IC), endometriosis or a whole host of other conditions related to reproductive health. Even though these conditions are so widespread that it’s likely that every womxn in the UK will experience some sort of reproductive health problem in their lifetime, treatments are extremely limited.

Many people find experimenting with diet to have some effect, however, for most, chronic pain management becomes a reality, often for the rest of their lives. This, combined with the fact that the journey to diagnosis is often marked by disbelief, disorganisation and lengthy waiting times, means that dealing with a reproductive health problem can often feel like an insurmountable task.

On October 6, the UK government committed to researching endometriosis, a condition which affects around 1 in 10 womxn in the UK, making it just as common as diabetes.

While this breakthrough should be celebrated, it is not just this condition which needs a reappraisal, but rather the way womxn’s health is dealt with by the whole medical profession.

With the difference in the ‘gender pain gap’ finally getting some much-needed attention, shado decided to sit down with four different women and hear their stories, discussing issues such as diagnosis, treatment and how it’s affected their lives. Each story highlighted a different aspect of the issue: stigma, deterioration of mental health, lack of research and how communities have come together to battle these issues.

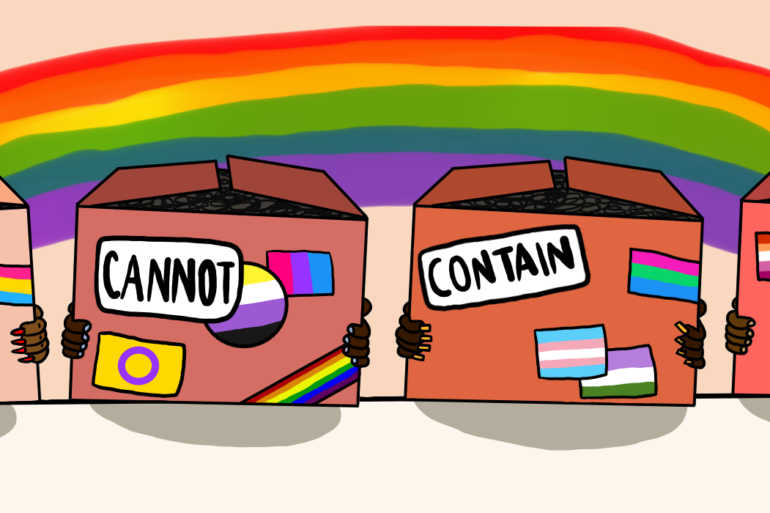

We also asked each of these women to describe their pain, allowing something which is so often side-lined or marginalised to take centre stage, in the form of an artist’s illustration.

-

Ella

“It was like 127 hours, that film where James Franco’s sawing off his arms – that was the level of determination I needed to get out the front door and crawl to a cab and then make light conversation with the Uber driver.”

Ella is a young stand-up comedian. This comes through as we’re talking in her guardianship in London. Despite the sobering content, we spend a lot of the time laughing. Unlike a lot of the other people we spoke to, Ella hasn’t been ill for very long, although the longevity of her illness has done nothing to dull it’s intensity.

Ella first sought out medical attention after experiencing extreme weight fluctuation and chronic pain. However, after being told following numerous visits that her pain was psychosomatic or merely period pain, she started to question if she should return.

“I didn’t want to go back to my GP as I felt ridiculed. I first saw a female doctor and it was with a smug smile she told me it’s just my period … and nothing really alarming”.

After waking up screaming in agony Ella managed to take herself to an NHS Emergency clinic. However, was turned away after the doctor diagnosed her yet again with period pains, despite the fact she wasn’t menstruating.

“So, because my infection went unchecked and because they just ignored my pain and didn’t investigate it – I developed two four cm by four cm abscesses on each of my fallopian tubes from untreated pelvic inflammatory disease, which had infected everywhere.”

Ella points out that 1 in 10 people with uteruses have PID in their lifetime, so she can’t understand why this diagnosis wasn’t more easily reached. Furthermore, 1 in 10 of those people become infertile due to scarring from the disease.

“So now I’m that statistic, but it was wholly preventable. There’s no there’s no rhyme or reason as to why my pain couldn’t have been pinpointed, believed and investigated. I could have gone on a dose of antibiotics and have it out the way, but now I have to live with the life-long repercussions of these doctor’s doubt.”

Ella’s chances might be slightly better than 1% at conceiving. To determine this, she would need to go through a series of invasive tests, which aren’t available to her due to the fact she’s only 25 and is not actively seeking to become a parent.

She balks at the ridiculousness of this, stating that when she finds a prospective partner, she wants to be able to say “so this is the situation you’re dealing with – are you in? Are you ready?”.

Ella’s issues with misconceptions from medical professionals unfortunately didn’t end with diagnosis. Around ¼ of people get PID due to an untreated STI, which therefore steeps the condition in stigma. “The assumption is that you’ve got yourself here because you’ve been negligent with your sexual health” Ella states. She continues that she was treated as though she was in some part to blame, which despite being incredibly misplaced, also didn’t pertain to her situation.

Ella has found a unique way of dealing with her condition. After turning up to a gig without any material or her guitar, in a large part due to the spacey effects of her pain medication, Ella started talking about her illness and everyone’s reactions to it. This then became her newest show. In it she explains that when most people hear her chances of conceiving, they try to convince her that she might be that 1%, or in her mother’s case, that Ella’s chances are more like 50/50. To which she replied, “you can’t just make up a fact mum, you’re not Donald Trump”.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

Sophie

“It’s really, really difficult. There was a point where I was like, I don’t think I can actually carry on doing this. It’s the darkest, scariest place to be when you feel like no one believes you, especially when you start internalising it and start thinking, maybe this is all something I’ve created …”

Like many of the women I’ve interviewed Sophie radiates strength. She can talk about her conditions (endometriosis, IC and IBS) and symptoms with a level of detachment I assume is a by-product of having to repeat herself to doctors so frequently. But it’s also more than that, Sophie’s strength is a symbol of the silence imposed on womxn by the medical services. People like Sophie shouldn’t have to be strong like that – they should be able to show their pain and have their symptoms listened to.

Sophie is a food business developer for a social enterprise. At 25, she’s been dealing with symptoms of her conditions for about five years. These have presented as chronic pain and weight fluctuation which has intermittently left her unable to work, go out, or even move, for nearly a fifth of her life.

After being bounced from doctor to doctor – many merely prescribing a hot-water bottle – Sophie hit breaking point after she stopped taking her contraceptive pill and her condition accelerated exponentially.

“I went to A&E 20 times because I couldn’t not be sick. I consistently couldn’t eat or drink and was just crippled on the floor. It almost gave me a bit more power because I was like no one can ignore this now. I will go and be sick on a doctor if I have to.”

Due to the lengthy process of Sophie’s diagnosis she has also battled with a codeine addiction, on top of dealing with her many faceted conditions. By the time Sophie finally had an operation to remove the cyst on one of her ovaries and clear her endometriosis she had been taking 14 30 milligram dihydrocodeine a day.

“Enough to kill someone if they took it for the first time” she states. “The doctors were also very happy to prescribe it to me if it meant that I left their surgery.”

While Sophie waited for her operation, the date of which was constantly pushed back, she was oscillating between extreme pain and a near comatose state.

“I remember sitting in the pub with my friends and I was like, I think I might be dribbling but I don’t have the energy to wipe my face”.

The date for Sophie’s surgery finally came around – however upon arrival her doctor told her that something wasn’t quite right. The small cyst she had come in to get removed was in fact a fast-growing tumour. He had no idea why no one had told her this, why they hadn’t operated and no idea whether it was cancerous or not.

Her surgery, which took place after receiving negative cancer results, was meant to take 45 minutes. This ended up taking three and a half hours due to the extensive nature of her endometriosis.

It wasn’t until six months after surgery that she finally had her diagnosis. All three of her conditions affect each other, and the codeine due to its dehydrating effects had been making them worse.

Despite the length of Sophie’s diagnosis and relative extremity of her condition she constantly tells me how privileged she is, concerning her understanding job and partner, but also due to her race and level of education.

“I genuinely threatened to kill a doctor and punch the shit out of a door and the police weren’t called. I literally like lost it completely and they’re like, she’s angry – poor thing she’s probably premenstrual.”

“I think women have a really shit time in hospitals, but then I think not as hard as anyone that’s not white or English isn’t their first language.”

She also touches on the debilitating mental health affects having a chronic pain condition can have.

“I think I would kill myself if I had to go through it for much longer. I felt like there was no way out and you can’t live with chronic pain without a solution”.

The condition also forced her to change as a person, going from someone who was very active and socially outgoing, she transformed into someone who needs to spend a lot of time in bed.

This in turn dominated her conversation, as recounting her week meant describing one so marked by pain.

She recalls getting into a destructive mind-loop, often thinking: “This is all I talk about. This is the only thing that defines me, this is who I am”.

However, since the surgery Sophie has stopped taking the codeine, changed her diet and started taking amitriptyline, a drug initially designed to battle depression but is now used to manage pain.

This treatment has allowed Sophie to once again take an active role in her recovery, to schedule it so her periods and meetings don’t coincide with her flare ups. She’s still in a lot of pain, but at least this way she can plan beyond it.

-

Hazel

“It’s because it’s a woman thing – if you got that pain in your willy – you wouldn’t like it.”

Hazel is 74 and has lived in Kennington since 1981. She suffered with debilitating pain for most of her life, but it wasn’t until she became so ill that she had to have a hysterectomy at 37, that she first heard the word endometriosis.

Despite going for years without diagnosis, Hazel was aware that her pain was abnormal. The conviction and openness with which she described it to me was admirable. She tells me about the further intensified culture of silence and misunderstanding around reproductive health she endured while growing up, calling it: “all very hush-hush”. I was aware of this deepened stigma; however, it was Hazel’s own candour that surprised and impressed me. She spoke so openly about her reproductive health, despite this being one of the first conversations she had ever had about it.

Talking to Hazel did demonstrate the ways in which we have developed as a society concerning attitudes around reproductive health. For example, Hazel described calling girls father’s while working as a TA to inform them of their daughter’s first period and their response being “’Oh, I’ve got some old shirts’ or ‘I’ve got some old sheets’.”

Or, devastatingly, when Hazel told me about her experience when she miscarried.

“He [the doctor] was so unsympathetic, you know, he said ‘just keep it in a bucket and we’ll come and look at it later’. My Roy had him up against the wall.”

However, it became abundantly clear during our conversation that attitudes have not developed far enough; that the dismissive culture around womxn’s pain hasn’t changed, and even more shockingly, neither has the treatment.

Growing up, Hazel often had to miss school and then later in life days of work due to the intense pain she experienced during her period. “I don’t think I ever got used to it” she explains, “every month I used to dread it”.

While her mother did take her to the doctor’s she eventually stopped going, becoming disillusioned after being continuously prescribed paracetamol. Codeine was available when Hazel was seeking treatment, but she explains “Yeah, and they were a little bit better, but I’ll still be in bed for a day with a hot water bottle on my front and on my back. Still being sick and still keep wanting to go to the toilet.”

She states that everyone’s attitude was “get on with it. They didn’t care”. Even her hysterectomy treatment was abnormal. Hazel explains that normally “they’d let you suffer. Basically, until you’d reach the age when you went into your change.”

“Obviously after that you’re alright. That was heaven!”

Leading up to this however it was just pain medication and hot water bottles.

“Try and get yourself comfortable and put a pillow under your bum – anything that would like alleviate it a little bit. Not much did.”

-

Saschan

“Yeah, so I wasn’t best pleased, but I also was very vulnerable and didn’t really feel like I was in a position to argue because when you’re in pain, you just want someone to take the pain away. That’s the thing that you’re primarily concerned with and at this point I’d been in pain for months and months.”

Saschan’s story, like most womxn’s, is characterised by disbelief, misdiagnosis and overarching pain. However, Saschan managed to channel all of this, and her anger concerning the lack of support she was receiving from her doctors and decided to become that support for other women facing similar situations.

She created the Womb Room after her first surgery when she was just 19. This was to remove a 19 x 22 cm cyst that was growing on one of her ovaries. Reaching this point had been difficult. Saschan had a surgery booked for five months after her diagnosis, however, was living in unbearable pain. She was forced to undergo months of being told she wasn’t anyone’s concern, unnecessary and painful internal exams and multiple interrogations until anyone took her seriously, despite having proof of the cyst in the paperwork she carried to each appointment.

She was eventually forced to see a private consultant who informed her she needed surgery immediately, that in her current state her cyst could rupture, and she would die of septicaemia before she could reach a hospital.

During surgery they drained over five litres of fluid from the cyst and ended up having to remove her right ovary and fallopian tube – an outcome she had been assured was very unlikely. They also stated that due to the weight of the cyst, even if she had lived until her scheduled surgery in July, she would have needed a complete hysterectomy.

After this surgery in 2011 Saschan found out it would be extremely difficult for her to conceive. Despite not considering this option seriously previously, having it ripped away made her question everything.

“Who’s going to love me? If I can’t have kids who’s going to want to be in a relationship with me?”.

This led to independent research, unveiling terrifying statistics such as the relationship between women who have their fallopian tubes removed and then suffer from early on-set Alzheimer’s.

To deal with this overwhelming sense of confusion and dejection, Saschan started to blog, quickly reaching over 20,000 people, some of whom asked for advice and sent in questions.

She was approached after giving a talk at the Royal Society of Arts by a man who made her realise her blog could become a business.

The first thing Saschan wanted to achieve was to educate young womxn in reproductive female health.

“The idea was that to teach young womxn how to understand their bodies, how to self-advocate and recognize the symptoms when something is wrong. If we do that, we can encourage early diagnosis so that they’re not having to suffer for long periods of time”.

She also started to target businesses: “if you consider that womxn make up nearly 52 percent of population in the UK and statistically nearly every single womxn will present with a reproductive health problem at some point during her life, why is our workplace not aware of the issue?”.

She teaches businesses not only how to support their staff but how to encourage an open atmosphere, which in turn supports a better working environment. She also teaches employees how to effectively navigate the NHS system.

“It’s literally just small bits of knowledge that you piece together when you move through the system that you find out are actually really invaluable when you give them to other people”.

The Woom Room now also runs independent events, inviting different medical professionals to speak on a range of topics, from alternative medicines to supporting your pelvic floor.

She states that “it’s been really nice having medical professionals with lived experience of reproductive health problems that are happy to disclose their experiences. It makes you realise that your doctor might have an experience of their own”.

Saschan was also recently appointed to the board of the College of Obstetricians and gynaecologists as a consultant lay person, to ensure that research and practice is inclusive for womxn. She has underlined to them the importance of having connected services to avoid unnecessary surgeries and a delay in diagnosis.

She told them: “you have womxn go through hysterectomies or really big surgeries and then don’t offer counselling. These surgeries can completely change the concept of who you think you are or what you think womxnhood means; you have to relearn that part of yourself from scratch which is a big emotional burden without a support system”.

She advised: “you have to do one of two things. You’ve either got to give people the knowledge to navigate your system or you must change the system to fit their needs.”

“So hopefully, they’re going to start working on that. I’m not going to hold my breath”.

The Pain Project is on-going, with hopes to tour around the UK, speaking to a range of people about their experiences with reproductive health. We aim to be as inclusive as possible, highlighting how different intersectionalities can affect this experience. Please send in your stories, we’d love to hear them.

Illustrations by Sakina Saïdi

Sakina is a French Moroccan illustrator living in London. Her work focuses on the beauty of womanhood. She loves to represent the world around her using a cheerful palette with a positive and motivational message.