During the final breaths of July, I found myself seated at a square dinner table on a cobble-stoned terrace of an osteria located in the heel of Italy’s boot. The table was cloaked in a pale, unironed yellow cloth and seated around me – across and to my left and right – were my friends, eager to feast after a rather taxing mission to park a car. The odyssey to find the parking spot resulted in us missing our reservation by an hour but, at last, we made it.

The following day would take us to Paris and, after many languid lounges around the pool, cannonballs into rocky grottos and more tarallis, spritzes and gelato than the World Health Organization would recommend, we were set to conclude our Italy leg with a meal among the locals.

In front of us sat four fresh pastas that we rotated to the right, with only the sounds of our communal knives and forks clicking to accompany us in the first few moments. We recounted our last few days, comparing the sights to the eternal vacation scene in Sally Rooney novels but, in our story, we actually liked each other.

As we skimmed the dessert menu, my friend’s attention was drawn to something below the table, a stirring that was out of my view. It appeared his phone had buzzed and, as he pulled the glow of his screen closer to his face, he exclaimed an all too familiar phrase, “It’s Time To BeReal!”

I scoffed and rolled my eyes as if having an allergic reaction to the mention of the app. “BeReal is for the birds,” I announced as my mind cycled through rationale for how transparently vapid the idea of sharing a selfie that suggested candidness seemed. After all, wasn’t all social media, media and, therefore, performed?

But over the next few days, as we traded our spritzes for Sancerre, I found myself stuck on how often I performed online and how I chose to narrate my travels digitally. I was already saving pictures in my Google Photos album for the inevitable “dump” I’d share on Instagram after my trip. I was set on finding wifi in the airport so I could post my favourite Beyoncé song within the first few hours of RENAISSANCE being released. An essay I had written had been published while abroad and I felt a pressing need to announce it to my followers. All of this sharing and posting, intricately weaving together a fabric of how I wanted to be seen online. An online proof of life. Maybe, I was one of “the birds,” too.

The Bowels of The Internet

We live in a world where our online selves are becoming increasingly difficult to separate from our physical reality. The videos we share online and the photos we “dump” become digital appendages, pixelated limbs, just as dexterous as our real life organs. As such, it is only natural that we feel ownership over the digital selves we author as we wield them to source capital and clout.

Gone are the days of solely relying on a resumé; the online avatar has superseded in becoming the billboard for future opportunity and financial gain. Instagram baddies earn dividends by dropping their CashApp link on IG Live, Twitter users achieve book deals and lucrative writing gigs for their clever online quips, and OnlyFan angels score big through online collabs that keep a steady roster of subscribers engaged. With this momentum, the online self has become cocooned to the risks of the offline world.

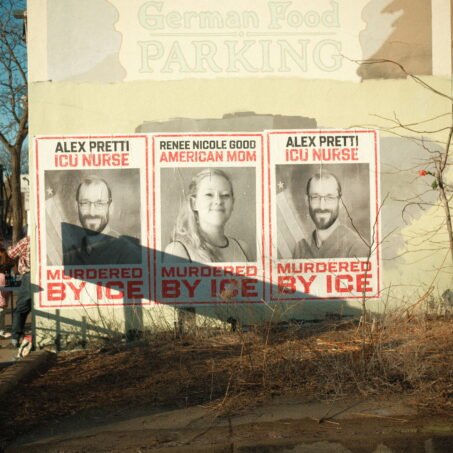

The fear of online cancellation becomes distant, in the rear view, as we motor towards virality, gain and affection. There was a time where what we performed and announced in the digital space could spawn negative repercussions for our “real life” identities. A bad tweet could lead to unemployment, following the wrong politician could require a notes app apology, a nude sent to the incorrect audience might end a career. Perhaps, we are still in this time.

To counter the online wave of performed wokeness and its shallow morality, the idea of “post-cancellation” – being beyond online condemnation – has begun to assume form. “Alt-right” Twitter users joke that they are post-cancellation, fashion brands’ dawn iconography that announce that they’ve been “cancelled twice” and yet are still active.

Artefacts of this theology can be sourced from many scenarios. In one scene, an individual can be “cancelled” so frequently that each new repercussion faced is blunted and less consequential than the previous. This is true for our most polarising Geminis: Kanye, Trump and Azealia. It is progressively harder to “cancel” someone when so much of their body of work – their music, their podcasts, their opinions – live online, detached from their physical being. By cataloguing oneself digitally, your reach is magnified and your values can live on in perpetuity, outlasting your physical form. It shouldn’t be a surprise that the aforementioned Geminis’ largest gripes are when they risk being deplatformed from a social site; it’s the closest thing to exile we have in the modern age.

Alternatively, the concept of “post-cancellation” may refer to the lack of materiality of the consequences faced from an online dispute, positing that we, as a society, are fatigued by the idea of cancellation. We fail to respond with repercussions that have real teeth. Perhaps, the fangs of justice are dulled in the interweb. Or, maybe, we are just lazy.

Regardless, it appears as though people are more comfortable bringing their full selves – bodies, feelings and beliefs – online without a fear of substantial retaliation. Shit posters post, risky photos are shared on Instagram Close Friends, controversial political opinions are Patreoned. In a way, the online self is more liberated than the in-person, furnishing a metaverse where our online avatars may be authentic, perhaps even more powerful, than our offline. An online orchestra of truth.

A Body Online

R&B crooner Ari Lennox captures the fearlessness of baring it all online, quite literally, on her sophmore album age/sex/location. On the project’s standout track ‘Leak It,’ with the help from singer-songwriter Chlöe, she boldly proclaims that she will leak her own sex tape because she’s “not ashamed.” There’s power and rebellion in this declaration as it’s in opposition the antiquated narrative of a straight woman’s sex tape being leaked by their male partners without consent, whether fabricated or not.

There is something freezing about Lennox’s desire to platform her own intimacy as it counters the prevailing woman-as-victim narrative we’ve consumed for years. On this song, Lennox is not the victim; she’s the commander, the orchestrator.

Through her towering vocal ability and her lyrics that focus on her body, she has complete agency. Her online sex tape becomes another appendage that she is in full control of. ‘Leak It’ has quickly ascended to being regarded as one of the album’s strongest songs and serves as an effective symbol of the shift in perception around our digital selves. It’s hard to imagine that a song of this material would have attained such positive praise in the previous internet era of Paris and Perez Hilton.

Both Hiltons, victim and perpetrator, act as symbols for an internet that’s in direct opposition to the one Lennox operates in. In Lennox’s internet, the sharing of her body online affirmed and empowered while in the digital sphere of the Hiltons, where an online body was more commonly shared without the subject’s consent, the internet aroused feelings of humiliation and powerlessness.

In Lennox’s world, the one we live in today, the internet has shifted to provide greater controls that bring agency back to the user. Users can now send expiring content that cannot be saved by recipients on applications like Instagram Vanish Mode, WhatsApp Disappearing Messages and, of course, Snapchat. An audience of trusted admirers can be curated to receive content through features like Instagram Close Friends and Twitter Circles, offering more control to the user. Finally, this audience can be monetised through subscription services like OnlyFans, unlocking a new level of financial prosperity that only a body online can garner. Through this advancement, the new internet not only allows for online identities to generate social capital but financial capital too through mediums that are more controlled and scaled than real life.

The Internet’s Face Card

Lennox boasts that her image within the tape has “no filter, no backdrop, no sparkles” but the decision to forgo these embellishments is more of an artistic choice than a virtuous one. Through the internet, its filters and editing tools, one has the ability to make adjustments to their image when constructing their online self, redesigning themselves and applying their own gaze for amplified clout.

In Tolentino’s essay “The Age of Instagram Face,” the writer details how the visages of online filters have found their way into cutting rooms of present-day plastic surgeons. Clients bring in the faces of celebrities whose surgically enhanced visage mirror that of an Instagram filter, a full-fleshed example of life imitating art. As the online self becomes more realised, more influential, one must explore the rationale in mirroring the offline image to match the digital. What’s the use in reupholstering a physical body that will soon be rendered obsolete in favour of a glitzier, digital model?

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

The Liberated Body

I most likely won’t use BeReal because I think it’s lame and “for the birds”, but I was wrong to think of myself as unique for rejecting it. The innocuous migration to an online identity points towards an awakened liberation, a liberation that only a body online can give birth to. I think of the online avatars I have created – Brendon as Instagram account, Brendon as published writer, Brendon as group chat jester – and recognise the innate power in recreating yourself in your own image.

A body online can generate capital through means that are more controlled, scaled and without consequence than reality. Through this, our online selves develop an imperviousness, a resilience that’s challenging to match offline. Our organs will fail, our bodies will be buried but our online identities will outlive us all. And so, while we are here, it seems logical that we build ourselves into omnipresent, indestructible digital deities, freer from the constraints of mortality until we muster the gall to hit delete.

What can you do?

- Read the article Love in the age of platform capitalism

- Read the article The I in the Internet by Jia Tolentino

- Read No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

- Metaverse – Real Life Magazine

- Check out groupchats by Brendon Holder