I first cracked open Invisible Child on the C train, shuttling up and down the West Side between my home and my workplace. There was something about the lulling anonymity, the feeling of being whisked between the different corners of the city in a subway setting, that allowed me to sink into the different side of New York City that Andrea Elliott weaves around the story of Dasani Coates, an 11 year old growing up in the shelter system in New York.

The topic of the subway is where our Zoom conversation starts, and fittingly, where a good portion of Invisible Child was written, in a book Andrea calls her “train notes.”

A reporter for the New York Times, Andrea spent nearly a decade immersed in the lives of Dasani and her family. Travelling from Brooklyn to the Upper West Side after eight-hour stints in Dasani’s world, she would jot down the thoughts and questions that swirled in her mind.

“Being with them was so overwhelming and in every kind of way, I felt every emotion available to me,” she explains. “It was provocative and fascinating and heartbreaking and inspiring – and every other adjective you could imagine.”

The face of an all-American history

Dasani is the eldest of eight siblings and half-siblings, with the entire family of 10 rounded off by her mother Chanel and her stepfather Supreme. The family is one of thousands in New York who are homeless, and the book follows them as they move from shelter to shelter, sketching a path through the welfare systems that surveil and control the lives of poor New Yorkers.

Throughout Andrea’s account, we witness Dasani and her siblings heating up formula in the middle of the night in the Auburn Family Residence shelter’s single microwave, and stealing bleach to scrub the neglected bathrooms. We follow her as she soars through the air performing acrobatics in Harlem with a fitness guru named Giant, and dancing in the subway with her siblings.

In 2014, Dasani holds hands with District Attorney Letitia James at Bill de Blasio’s inauguration as “the face of childhood homelessness”, yet a few years later, her family splinters under the pressures of drug addiction, inept bureaucracy and Child Protective Services. Spanning eight years of joy and tragedy, it is a bildungsroman of the new Gilded Age.

“I think of Dasani’s life as a vehicle for understanding so many aspects of our nation’s current reality and its legacy of slavery, its past,” Andrea muses. She compares the 600-page length of Invisible Child to Robert Caro’s first biography on former US President Lyndon B. Johnson: “Isn’t it almost implicitly saying that her life is worth every bit as much?”

Invisible Child stretches even beyond Dasani’s lifetime to sift through the pasts of her ancestors. With the help of interviews, memories, and tens of thousands of documents, Andrea constructs an unknown family history stretching to 1835, when the first trace of Dasani’s family appears, enslaved by Kedar Sykes.

Andrea uncovers the story of formidable figures like Dasani’s grandfather, who survived three battles in World War Two as part of an all-Black regiment in Italy, or the story of her grandmother Joanie Sykes and how she held together a family through the twin epidemics of HIV/AIDS and crack cocaine in the 1980s and 90s.

Working through a wealth of information from the numerous systems that track the city’s poor, Andrea was also struck by the major lapses in a family’s narrative and history that come from poverty and instability. To be able to find the property deeds that named the enslavers of Dasani’s ancestors, while losing love letters, photographs and traces of humanity, is “evidence of a very vastly unjust system” of memory.

“Every family needs a narrative,” Andrea explains. “I think the book has given Dasani a sense of narrative that she can hold to. I read the book to Dasani over the course of five days, and maybe five years from now she’ll feel differently, but right now she feels proud of it because it pieces together a history in her family that wasn’t known even to them.”

The heir to this invisible American dynasty, Dasani jumps off the page crackling with energy. Andrea remembers the first time meeting her: “Everything that came out of her mouth, I wanted to write down; she was so chatty and funny and electrifying.”

“We Are Sharing the Same Space, Yet We Are So, So Apart.”

The reader experiences New York through Dasani’s own eyes – her precociousness and wry perspective on her situation sticks with you long after you set the book down. One of the most memorable passages for me is when she describes the obstacles she faces in life as a video game, populated with villainous social workers, bullies, and maths teachers hurling numbers at her. Winning the game would mean finding a stable place to stay, while losing the game would mean returning to the Auburn shelter, with its roaches, mould and neglect.

Reading this, I felt like my console had been set to easy mode. One of the things that stunned me was that Dasani and I are the same age – we were born five months apart and grew up in the same vibrant city, yet our experiences are worlds away.

I write this article from a position of immense privilege, in a warm Columbia University apartment, trying to see the city through the eyes of a girl who has lived experiences that would fill lifetimes. I wondered if we had ever crossed paths. The power of Dasani’s story comes from its reminder that “we are sharing the same space, yet we are so, so apart,” forcing the reader to examine the barriers that render her experiences invisible to others.

Andrea first chipped away at these barriers in 2013, when the New York Times ran Dasani’s story on the front page for five straight days. As the news caught and Dasani’s story spread, Andrea remembers the feeling of riding the subway and seeing commuters glued to their phones, to the physical paper, transfixed by this glimpse into a life so foreign to theirs, shaped by the forces of poverty, family and history.

At one point, she couldn’t help herself, and let the man sitting by her know that she was the reporter behind the article. “It turned out to be the worst person I could have said it to,” Andrea laughed. The man worked for the mayor’s office, and was not exactly pleased with the stance expressed in the article. But at the end of the day, a reaction was a reaction.

“People were a lot of things, but none of it was neutral, right?” Andrea says. “You can’t get people engaged with those issues, absent some kind of humanity that is driving it.”

“Window dressing” disguised as homeless policy is part of the problem

In the first week of December 2022, New York has hit a historic high in terms of the census of city shelters—66,000 New Yorkers are in the shelter system, about 20,000 of which are children.

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

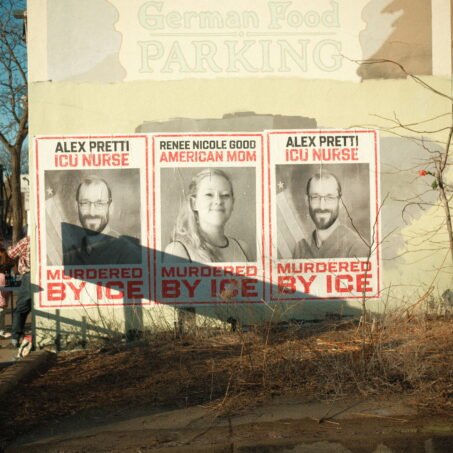

Engagement in the issue of homelessness today is becoming increasingly dehumanised. Under Mayor Eric Adams, new punitive homeless policies have been driven by an increasing perception of fear among New Yorkers.

Controversially, the Adams administration recently announced an anti-homeless strategy that would have the state involuntarily hospitalise unhoused people with “visible mental illness.” This is matched with a plan to reform the shelter and housing services system that advocates warn is not ambitious enough to break the cycles of instability and homelessness.

Over the past three years, the number of respite centres for unhoused New Yorkers to access drop-in services have fallen by about half, leaving a vulnerable population with even fewer resources than before.

To now criminalise mental illness in the visibly unhoused, and exacerbate a sluggish system with scarce resources that cycles through people in order to provide a perception of safety – what Andrea calls “window dressing” – avoids the root of the problem.

“It’s just evident that the administration’s approach has been to police the visible homeless by kind of driving them out of sight. It is surface level and it is about perception,” she says. The visibly unhoused and mentally ill are only a fraction of the New Yorkers currently homeless. The disproportionately carceral response to their particular crisis distracts from the other ways homelessness manifests and goes unaddressed by the city’s broken systems.

Andrea illuminates these issues – what she calls “feeding the reader their spinach” – through the worldview of Dasani and her family.

In a particularly difficult part of the book, Andrea writes about how Supreme, unable to access food stamps in Chanel’s name, cut off from gas in subsidised housing, petitioning for renovations to fix infrastructure issues, and juggling seven children alone with no income, faces accusations of neglect due to the condition of his home.

The book trots the reader through the brutal process of family court, custody battles and foster care, encountering the street-level bureaucrats for whom homeless policy forces them to take an unsympathetic approach on an overwhelmingly human problem. Readers sit with the children in specialised intake centres, with the entire family in offices in the Bronx waiting to be rehoused, and we watch as Chanel and Supreme lose custody of their children in 2015.

“A kid is only as well off as the kid’s parent.”

One of the central lessons of Invisible Child is how needs go unaddressed because interventions aimed to lift families out of poverty refuse to meet families where they are, furthering this cycle of insecurity.

Dasani’s life takes an abrupt turn in 2015 when she secures a place in the Milton Hershey School, a private boarding school in Pennsylvania for impoverished children to study for free. At Hershey, her life becomes stable, scheduled, and she flourishes in school, but far away from New York and her family. It falls into a paradigm of success and social mobility carried out on the terms of an American Dream dictated by a predominantly white middle class.

Andrea contends that leaving your roots should not be the only option to escape poverty, noting that Dasani’s choice to leave Hershey’s “Hollywood hope story” and return to New York was “her story as she wanted to live it, on her own terms,” despite how some of her readers may feel. At the end of the day, meeting families where they are comes in the form of investment in the family structure. By providing a safety net, including stable housing, policymakers can empower families to survive and thrive.

“You do wind up kind of fighting upstream with all these other programs because a kid is only as well off as the kid’s parent,” Andrea tells me. “All these years later, what I’ve come to see is that it’s impossible to separate Dasani’s present childhood from the childhoods that came before. It’s not about just this one child who’s invisible to the city around her, but it’s about the childhoods that formed the adults that are invisible inside them.”

One question I was desperate to ask Andrea on our Zoom call was what to do with the glut of spinach – in the face of such intractable, complex and immovable systems, what can one person leverage their privilege to do?

Like most of life, there is no easy answer. “I’ve always been more comfortable exposing problems than trying to figure out how to fix them,” Andrea admits at first. “It’s a cop-out to say this is too complex and what can I really do? because there are a lot of kids out there who need help and resources and it’s not that hard to provide those things.”

She shares an email she received from a teacher who quoted lyrics from the Scottish indie band Frightened Rabbit, a song called ‘Head Rolls Off’:

When my head rolls off, someone else’s will turn

And while I’m alive, I’ll make tiny changes to earth

At the end of the day, it is a matter of turning heads and of seeing. “To enter the life just for even a brief period of a kid like Dasani in the role of friend, or – I don’t wanna say mentor so much a witness – these are incremental tiny things that, you know, maybe feel hopeless in the grand scheme because you’re only making an impact on one kid’s life. But I think, in the world, change gets created incrementally.”

What can you do?

Find your copy of Invisible Child at your local independent bookstore, or on Indiebound.

Organisations that provide welfare and shelter to unhoused and homeless populations in New York City:

- Coalition for the Homeless

- Goddard Riverside Community Center

- Ali Forney House (focus on LGBTQI+ homeless youth)

- Women in Need NYC

- The Bowery Mission

Read:

- Evicted by Matthew Desmond covers the causal relationship between poor housing policy, evictions and cyclical poverty in Milwaukee, WI during the 2008 Recession.

- There are No Children Here by Alex Kotlowitz, a biography following two boys as they grow up in the public housing projects of Chicago in the 1990s.

- Andrea recommends Tracy Kidd’s book Rough Sleepers, and for individual actions, would direct people to Coalition for the Homeless’ How to Help Page.

If you are interested in issues related to housing read: