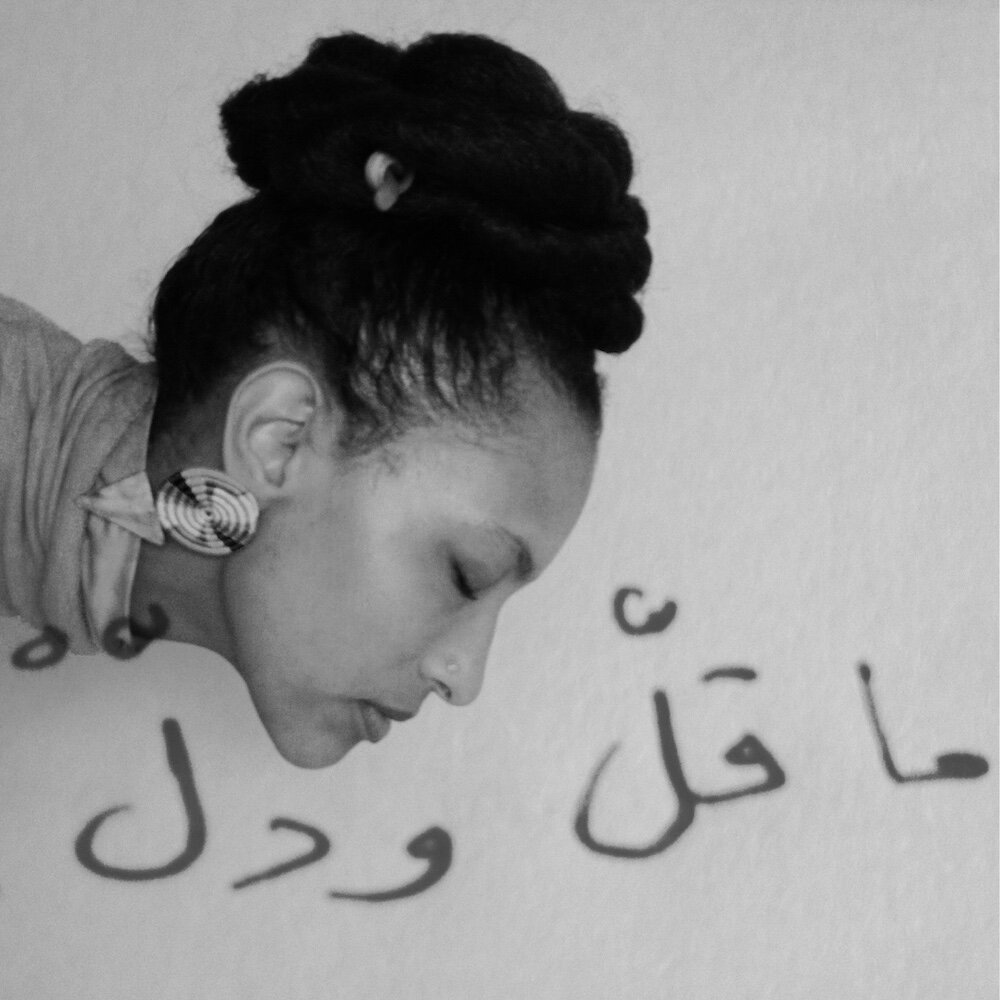

There aren’t very many activists in the world these days who lead with love – but Jessica Horn is one of them.

A feminist practitioner “situated politically in Pan-African feminism,” she works to ensure women’s rights to live “pleasurable embodied lives” free from violence. Jessica says that she’s here to “turn feminist visions into freedoms that are felt in everyday life.”

What she does is perhaps less important than how she does it. As she says herself: “I have always been interested in the process. As a society, we spend a lot of time focusing on the outcome, but the reality is, it’s the process which makes change happen.”

Jessica shares that for much of her life, she’s been “thinking about how we can better structure and better resource the work we do, so that it doesn’t end up breaking us. Instead we need to actually succeed in creating the worlds we want.” These are the principles that guide Jessica’s work.

Regenerative philanthropy

Jessica is currently the East African Regional Director for the philanthropic organisation Ford Foundation. Traditionally a field that gatekeeps wealth and often actively reinforces white-supremacist socioeconomic hierarchies, you might wonder what she is doing there.

Jessica explains it simply: “the need for change exists, and so do the people willing to risk their lives for it. Sometimes they have all the resources required, but often, they need money.

Philanthropy can therefore be useful in allowing other people to connect to the movement.”She’s also been, rethinking the power structures within philanthropy, helping to develop participatory funds and supporting feminist funding in order to support work happening in the East African region.

Her work is aimed at regeneratively revolutionising the philanthropic space – emphasising that i’s the how that matters, not the what.

Jessica’s worldview is critically nuanced and expansive: there is a recognition that nothing (philanthropy included) is as black-and-white as it appears, and that we cannot be stuck in rigid frameworks of thought. How her approach came to be so expansive is evident – from the influence of her ancestral lineages.

East African feminism

Her identity as an East African feminist is integral to her work, both within and outside the Ford Foundation.

Currently, Jessica is working on a book on African feminist praxis and imagination. She’s also involved in documenting, historicising and archiving in the form of a creative documentary project about African women’s tattooing, scarification journeys and histories. On the varied and dynamic nature of her work, she says: “To me, it all makes sense: it all has roots in my passion around making the invisible, visible, and bringing out our stories, our politics and our vantage points, into the world.”

African feminism, where Jessica finds her theoretical, academic and familial roots, is expansive. In a previous interview, Jessica shared that: “African feminism is many things, because both Africa and feminism are many things.” African feminisms offer so much more than mainstream (white) feminism – which is damagingly universalising and uncritical of intersectional systems of oppression. They bring with them structural analyses of power, colonialism, patriarchy, and its various intersections, even before these were named as such.

“Feminism is a word in English,” is how Jessica puts it. If you’re after named instances of feminism and feminist movements, you would be looking but not seeing. “If you look across African history, you can always find and trace, individual, and collectivities of women who are resisting patriarchy in its different forms and its relationship to different dynamics.”

How feminism grew from independence movements

Jessica invites us to look to the Aba Women’s riots in Nigeria for an example of this, where women waged a successful uprising against intersectional discrimination, from a colonial regime, implemented by local men.

African feminism, Jessica says, “grew out of independence movements and liberation movements.” Many African feminists were in the business of pointing out that national liberation and independence movements were incomplete forms of liberation, “as the independent countries largely put in place patriarchal modes of being.”

Hence African feminisms were not only ‘feminist’ as we understand it today, but also “always retained that structural eye of the reality of being African”. They were intersectional feminists – before these terms were even formalised.

However, these histories never made it into the colonial, Anglophone history books that were circulated far and wide, and that necessarily influence how we understand history today. This is, as Jessica points out, “partly a problem of documentation, publishing and storytelling. Who gets to write, and who gets to prioritise what we know.” Her book, a contribution to archiving African feminists’ attempts to live their politics, will be one of many that are now flipping that script.

Expansive feminisms and creating space

But (African) feminism is so expansive not only because of what it defies and opposes, but also because it makes space for more. “Feminisms are always politics of resistance, and a politics of critique,” Jessica says. “But also on the positive, they are also a politics of imagining different ways of being.” It is prefigurative, it is praxis; it is imagining a better world and building it.

Here, we return full circle, to Jessica’s mission: to turn feminist visions into freedoms that are felt in everyday life.

African feminists have always been doing this. As Jessica says in her 2020 paper Decolonising emotional well-being and mental health in development: African feminist innovations: “Through activist praxis, we also build knowledge and insights into how we can contribute to transforming the world in the image of justice, and away from structural and direct violence.”

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

African feminisms are grounded in pleasure. And as author and clinical psychologist Taiwo Afuape says: “in the context of oppression, [pleasure] is interference, interruption and hope.”

Revolutionary love and radical care

African feminisms are also grounded in revolutionary love, and radical care. Jessica has written extensively about movements of HIV positive women on the African continent.

She explains: “People were ill and for a long time, and most people didn’t have easy access to quality antiretrovirals, so people were dealing with quite serious effects of HIV and AIDS. Looking after yourself was like a life or death question.”

“Economically marginalised women started teaching each other affordable, accessible, home-based remedies and healing practices. These were simple, but deeply thoughtful. What a beautiful thing it is, for a community of people to say: we respect this body that you live in, and we want it to be well, and so we’re going to create a space and resources and support to actually make sure that you can sustain this body that you’re in.”

“Symbolically,” she continues, “there’s also a power in affirming that yours is a body that’s worthy of care,” in a society that neglected and stigmatised these very bodies.

As with the work done by these incredible women, radical care and heart is at the centre of what Jessica is doing – as she says herself, “you can’t do this work if you don’t hold revolutionary love fiercely in your heart” – is making space.

The power in the belief of the freedom to

The reason she does this is simple. “It’s always easier to argue and rally people around freedom from, to make a case about abuse and violation and violence and to appeal to people through horror, pity, extreme anger at injustice,” she says. “Freedom to is full of so much potent energy, transgressive energy, that it can sometimes actually be harder.”

African feminist movements, she adds, have been working on freedom to, and not just in the form of lofty ideas and ornate visions, but in experiments with practice. She cites the ways in which African women have been the majority food producers on the continent, and how they’ve always practised permaculture, which now people are looking to re-encounter, through seed libraries and seed knowledge. African women have always been interested in freedom to food sovereignty, to healthy, communally-managed ecosystems.

Jessica wants us all to ask: What else is going on in African feminism? Because African feminisms offer boundless lessons for our movements.

To me, one answer to the question Jessica poses is regenerative activism, which Jessica defines herself as “activism that feeds” – in more ways than one. “It has to be activism that contains the seeds of what we’re trying to sow: the joy, the positivity, imagination, and attempts to actually live egalitarian power.” Her expansive, life-giving, imagination-growing, infrastructure-building African feminism(s) are doing just that. It is a labour of and for (collective) love, and she invites us to liberate ourselves in this way too.

Leading with love, Jessica’s vision for our liberation, grounded in her ancestry, is just as irresistible as it is trailblazing. “We just have to do, because we have no time to wait.”

What can you do?

- Read the full version of this interview with Jessica on Advaya’s website

- Explore Jessica’s work on her website

- Read an article about Nego-Feminism by Tobi Onabolu

- Read more about Global feminist movements in shado Issue 02

- Read more about seed sovereignty HERE

- Find out how seed sovereignty is being used as an act of resistance in Kenya HERE

- Read, and cite, African feminists, who can be found on Feminist Africa journal, africanfeminism.com, The Charter of Feminist Principles for African Feminists, the Know Your African Feminists series produced by the African Feminist Forum, and the Black Women Radicals x African Feminist Forum collaboration documenting our African feminist ancestors

- Engage with and explore African feminist art and cultural expression

- Assume that in any struggle, African feminists are mobilising around it: and build active solidarity with them!

This is a series of articles co-published by Advaya and shado, in advance of Regenerative Activism 2022: a series of live online events, including three panels and one participatory workshop, featuring 11 incredible speakers, including activist and environmental lawyer Farhana Yamin, farmer and land rights activist Jyoti Fernandes, co-executive director of Green New Deal UK Fatima Ibrahim, lifelong activist Satish Kumar, and more. The event series will explore radical imagination and reclaiming the future. All sessions will be recorded and made available upon registration. Find out more and register here.