For years now, healthcare workers in the UK have been expected to go above and beyond.

The parameters of their job descriptions have become dangerously blurred, and at the peak of the worst global health crisis of the 21st century no healthcare worker was afforded the protections of furlough or working from home. Instead, they continued to work to ensure our health, at the risk of their own.

The vocation myth

This absence of clear workplace boundaries and protections are rooted in healthcare being framed as a vocation. Instead of a job with set working hours, conditions and employee rights, it is an act of benevolence. As a former NHS mental health professional, this idea was something I’d internalised.

I’d accepted what, in any other job, would have been deemed unacceptable.

Being out with friends and receiving a call to cross-check patient notes. Being forced to work a double shift after a colleague realises that their own illness means they can no longer stay on the ward. Having a young patient who is in crisis and needing more attention than their allotted 15 minutes, but leaving you feeling the pressure of knowing that if you stay you’ll fall behind on paperwork.

This is the all too common daily reality for healthcare workers. Too often we accept this as part of the job because we want to do what is right for our patients, even if it comes at a great personal cost.

However, as a collective, we are being pushed to breaking point, and we must confront the extent to which our ethics are being manipulated by a government which has no regard for patient care or our own.

The government has just about milked any efficiency from the NHS and has directly caused a system breakdown with widespread burnout of healthcare workers across the board.

However, the expectation held by our government, and shored up by the media, is that our ability and desire to help others is a resource that is seemingly endless. This upholds the arrogant belief that we will continue to show up despite the working conditions afforded to us.

Burnout

I first became frustrated by this framing of healthcare workers when I was redeployed onto the frontline as a COVID-19 vaccinator in 2020. I knew at the time that what I was part of was much bigger than me, in that it would save millions of lives, but at the end of all my shifts I would come home and cry, yearning for someone to care for me in the same way.

I felt selfish for having these thoughts and feelings because I knew that my work was important. If I did not help my team, or cancelled my shift, there was a real possibility that someone could die. I also had no context to compare this situation against. I had never worked in any other sector.

I did not have the language to describe it then, but I knew right away that this job was taking more from my own life than was normal or should be expected.

An age old tale

Almost two years later, I was confronted with research that gave me the language to express all of what I was feeling. A friend had retweeted the paper, ‘Obstacles to physicians’ emotional health – Lessons from History’ and reading this aptly captured and validated a lot of what I knew my colleagues and I were feeling.

Finally someone got it. I knew then that I had to contact the author, Dr Agnes Arnold-Forster to gain her insights. What Agnes gave me was confirmation and understanding that the reason healthcare workers are expected to work so hard for such little reward is due to the historical framing of care work as vocational.

Agnes explained: “Healthcare professionals, especially nurses, weren’t seen as professionals or even socially useful. Even doctors in the 16 and 17th century were seen as quacks and self-serving.”

Before 1880, receiving medical treatment in a hospital setting was rare. Working class patients would be treated at home, often reliant on the women in their lives or attended to through the altruism of doctors who were volunteering their care. It was not until the introduction of the poor laws in 1834 that any kind of welfare state was implemented. So, it was really only the elite who could afford to be seen by doctors.

Even then, it was not until the mid 19th century when due to the discovery of anaesthetics and antiseptic that surgery moved medical care into hospital settings. Because of this more formal location people began to see that nursing and other forms of healthcare required skill and training, rather than as a practice reliant on the altruism of others.

Despite the overwhelming medical advances which have occurred since this time, many of these legacies concerning our view of healthcare workers have remained ingrained. This colours society’s opinion of the reasons why healthcare workers choose their professions and what they will put up with in their commitment to caring for others.

The government’s manipulation

Modern medical professionals have recently been working to disrupt this selfless vocational narrative through posts across social media, where healthcare professionals including doctors, nurses, ambulance workers, public health workers are challenging this rhetoric by showing their realities, and highlighting the same struggles and weaknesses as any other workers.

Dr Kayode Oki was one of the doctors who was publically vocal about his experiences. I had been following him and his work as a unionist on Twitter. His thoughts were very clear:

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

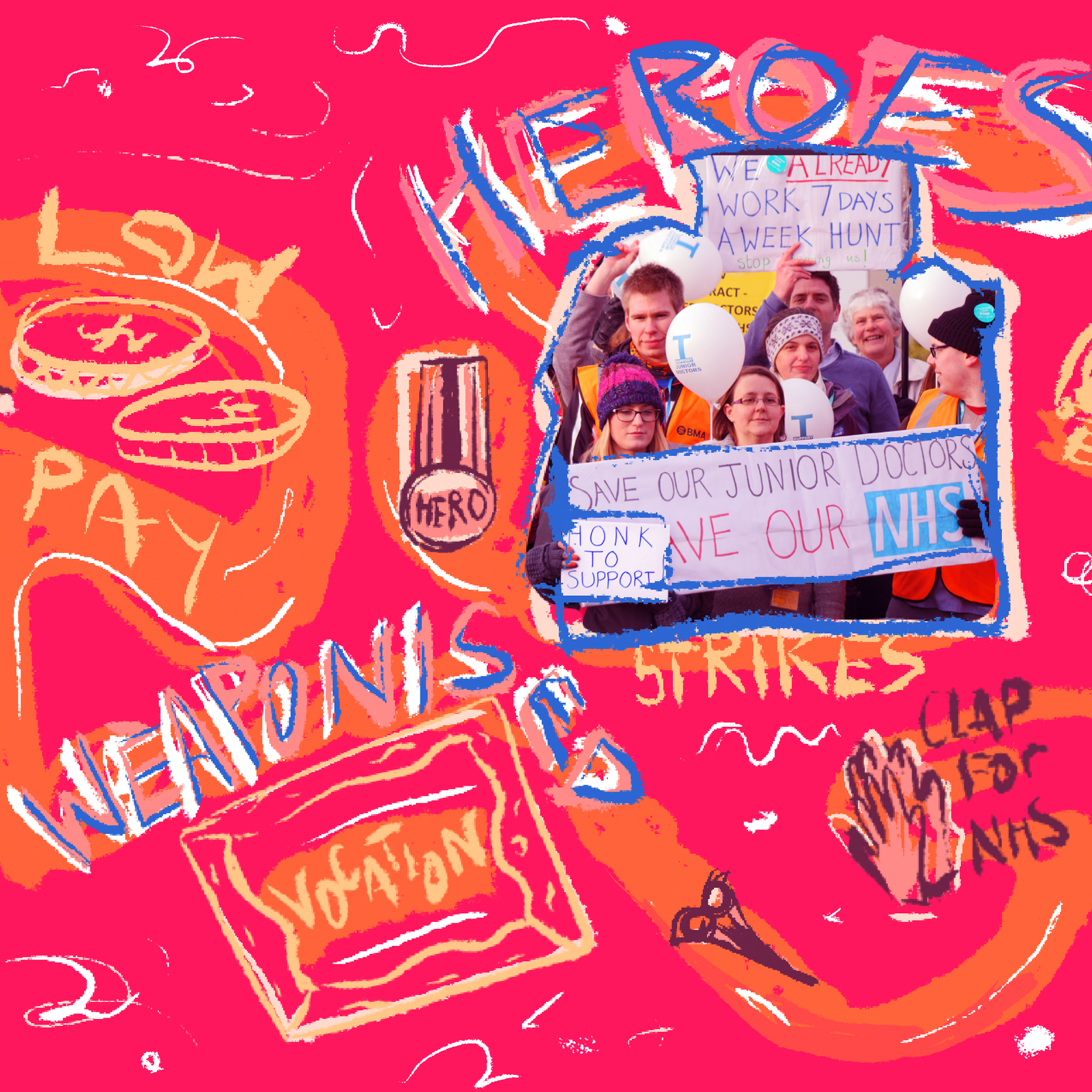

“It all started with the claps during COVID for me. I was still a medical student and I saw the narrative in the media about NHS Heroes and it scared me. There was a lot of rhetoric about NHS workers being on the “frontline” like we were soldiers. I was very uncomfortable with it. It seemed as if we were meant to sacrifice ourselves for the good of society. “

This media weaponisation of heroism among healthcare workers is dangerous because it diverts our attention away from ensuring the reciprocal social obligations to healthcare workers are also being met, including fair pay and working conditions.

Moreover, this framing of healthcare workers becomes a convenient political tool to deflect away from government negligence, and also shifts their responsibility in supporting workers and maintaining the NHS, to an individual level.

It is also seeping into universities and their marketing of courses. Daniel, a healthcare assistant from Liverpool mentions this indoctrination of healthcare at university level:

“Since higher education has been privatised, the marketing of any type of course, even those for ‘vocational’ professions, are very different from their reality. Even people who think it is their calling can realise, sometimes too late, that it really isn’t. That it’s not what they saw on TV or envisioned causes a real dissonance and an identity crisis for them. When we question the framing of any job as being a vocation, it is not just the media or government to blame – universities have a lot to answer for too.”

Breaking point

Chronic underfunding and privatisation has changed the landscape of the NHS into being run as a business where profits guide care choices, and patients and staff suffer. For example, one significant impact of years and years of underfunding and increasing demand is that accessing mental health services is becoming harder, with wait times of over 18 months being commonplace.

Additionally, the threshold for receiving treatment has increased, with people often having to reach crisis point to even be considered for referral for treatment. According to a report published by the Education Policy Institute in early 2020, 26% of referrals to specialist children’s mental health services were rejected in 2018-2019 . Clearly, the NHS has reached breaking point.

At present we are dealing with some of the longest waiting times ever known, huge delays and pressures to urgent and emergency services, dwindling numbers of GPs struggling to match the increased demand and a crisis in bed availability .

Furthermore, It is now becoming clear that due to working through the COVID-19 crisis healthcare workers are now facing long term illnesses such as long-covid, mental health conditions with a 25% increase in the prevalence of anxiety and depression. As the cost of living crisis exacerbates post-pandemic stress levels, NHS workers can now add financial destitution to the list of risks they are facing.

Strike action

These issues have been compounded due to the introduction of new legislation. The Minimum Service Level Bill (also known as the anti-strike law) which gives employers the power to penalise frontline NHS healthcare workers and threaten their unions into bankruptcy if they take strike action.

Whilst the Bill is still making its way through the House of Lords, if it passes without any amendments, the Bill will fulfil its aims of silencing workers and to stop them from fighting back.

Since October 2022, this has resulted in the biggest known wave of strike action from healthcare workers, with thousands of nurses, paramedics, and physiology workers choosing to take action. This action has continued to grow with 98% of junior doctors voting in favour of strike action.

Despite what is being reported by the government and mainstream press however, this crisis is not a byproduct of the pandemic, but is due to 12 years of political policies and choices enacted by a government who has ignored the needs of healthcare workers and the NHS at large.

This is what makes it so morally indefensible that healthcare workers in this position are now being abandoned by the very people – the media and politicians – who had previously clapped for them and hailed them as “heroes”.

The need for an anti-capitalist framework

So, how can we reframe this?

The giving of care is an inherently anti-capitalist act – giving without the profit motive of gaining capital back. However, as Beatrice Adler-Bolton and Artie Vierkant argue in their book Health Communism, the need for distribution of health services and provision of care, cannot be separated from the capitalisation of healthcare.

Fundamentally, what this means is that a socialised health system – which form the principles the NHS has been built on – cannot exist under capitalism. So, unlike many other jobs where patients are treated as clients, whom workers are trying to get to consume their service, it is the norm that healthcare workers will commodify their labour or services – they are expected to go above and beyond to meet the demands needed.

As the healthcare system is constructed like this, there is no alternative in the system’s current manifestation for healthcare workers. This then makes it harder for both workers and patients to understand it as just a job, as it becomes seen and too often enacted as a moral obligation.

Perhaps it works in our favour to remind the public that the jobs of all healthcare professionals are tough and uncompromising – but, in the end, a job where we should be entitled to fair working conditions and pay.

This is essential especially in the face of 12 years of Tory rule, where several anti-trade union legislation have been and continue to be passed. The Minimum Service Levels Bill is the latest attempt, and certainly will not be the last clamp down on the power of workers, threatening our right to strike altogether.

Regardless of how invaluable we are to our roles, it’s up to us to make sure that as the government forges ahead with its draconian laws, we put up a fight greater than they bargained for.

What can you do?

As a health organiser, it is clear to me that people need to support workers in taking back their power and collectively fight for workers’ rights. If you are interested in supporting healthcare workers or just learning more generally on the importance of strikes please engage with the following resources:

Read:

- Health Communism by Beatrice Adler-Bolton and Artie Vierkant which uncovers how health has been linked and exploited under capitalism. It serves as a manifesto and useful organising tool on radical approaches to our health

- Make Bosses Pay: Why We Need Unions by Eve Livingstone is an accessible introductory book on trade unions, and their inner workings for a new generation of workers.

- Lost in Work: Escaping Capitalism by Amelia Horgan is an introductory book which encourages readers to consider why and how work under capitalism is so bad, challenging our thoughts on work in general and organising around it.

- Tribune magazine runs continuous commentary and coverage of the ongoing NHS strikes, with first hand accounts from striking workers.

Other articles related to healthcare on shado:

- As Doctors we need to #Killthebill or we risk becoming a danger to public health – Shado Magazine

- Visa or not, immigrant healthcare workers are taking on as much risk as anyone else

- What is Reproductive Justice? – Shado Magazine

Podcasts:

- Death Panel is a twice weekly podcast about the political economy of health co-hosted by Beatrice Adler-Bolton, Artie Vierkant, Phil Rocco, Jules Gill-Peterson and Abby Cartus.

Donate:

- Donate to strike funds made available to support workers on strike. This includes strike funds for healthcare unions such as the Royal College of Nursing (RCN), UNISON, British Medical Association and Unite.

Twitter:

- Follow @strike_map on twitter which highlights when strikes take place across the country, for all public sector workers including NHS workers. Showing up to picket lines with snacks, words of encouragement and even pets goes a long way for workers striking and keeps momentum going.