This summer, huddled in the basement of the Palestine Museum of Natural History, eating za’atar popcorn with my colleagues after a hot day of farmwork, I watched Sameer Qumsiyeh’s documentary Walled Citizen.

Sameer is a local Palestinian filmaker, and we met over dinner at a mutual friend’s house. After learning about his film, which follows young travellers navigating the border system and exemplifies violations of freedom of movement for Palestinians, I knew I had to watch it. But I had no idea how impactful this film would be for me personally.

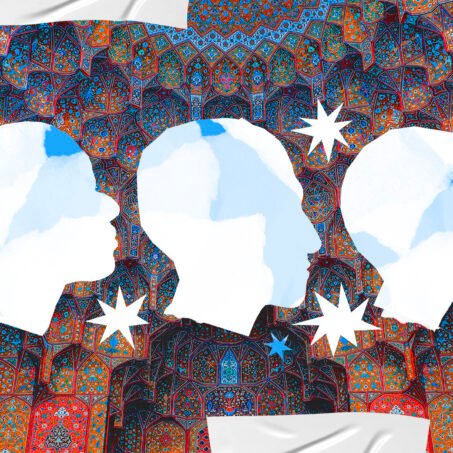

As an American Jew studying at the Jewish Theological Seminary and raised in a largely Zionist community, it has taken courage and a deep commitment to ethics for me to unlearn the political narratives I was born into. I study Middle Eastern Politics; I study Human Rights; I study Jewish Ethics. All of that leads me to nowhere other than Palestine. Growing up, I could have defaulted into anti-Palestinian sentiment. But my ethics and critical thinking allowed me to believe the victims and to understand that my historical education is not always correct.

As I watched the events unfold on screen, I realised how eloquently this film encapsulated my feelings about the theoretical and humanistic consequences of the modern border system in Palestine.

Through personal testimonies, Sameer’s film allows the viewer to build relationships with those who bear the brunt of the border crisis in Palestine. In addition to this people-first approach, he also cites international human rights law. Together these elements make a compelling argument for the abolition of the current border system.

Issues like human rights need to be understood through a personal lens. To fight for these rights is to understand that people are not political issues. Following the latest Israeli aggression on Gaza– commonly known as the “Largest Open Air Prison on Earth”– in August 2022, resulting in the murder of 49 people including 17 children, it’s more important than ever to acknowledge the humanity of Palestine.

Storytelling and human rights

To learn more about the power of storytelling as a vehicle to advocate for human rights, I spoke with Sameer earlier this month.

“I try to focus on the human stories,” he tells me. “The political situation comes in the background of the story, but is not the story itself. If you tell a story in an ‘academic way,’ through statistics and data, not everyone is interested. You need to tell the big problems in a relatable way.”

He relays an anecdote about being at a friend’s house while living in Europe.

“We were sitting in the living room and my friend’s mother called to me: ‘Hey, Sameer, they are talking about your country on TV!’ And on the screen, I saw images of masked men with guns amongst the rubble of destroyed homes. It was so offensive.”

He continues: “I was like, ‘Ah so this is how they see my country. Seeing Palestine only through the frame of the war makes people detach from Palestinians as human beings. They think, ‘That part of the world is at war so if people die that is their job to do, yaani [meaning], that’s a thing they do, so why would we care?’

Films that come from Palestine are important because they redirect the viewers to see us as normal people! Complex humans, who have dreams, aspirations and ambitions. But the political situation is making having a normal life impossible.”

Sameer tells me about other experiences he had while outside Palestine. “When I met people and told them where I was from, I started to feel like I wasn’t seen as a person, they only wanted to debate politics with me.”

Creative processes and creating empathy

By following young travellers and tracing freedom of movement between Palestinians and Westerners, Sameer’s film quickly explains how Western hegemony causes a crisis of borders resulting in violations of the human right of freedom of movement.

I ask Sameer about his creative process and how he had come to such striking and important conclusions in what seemed to the viewer like a matter of minutes.

He assures me that this process was actually not so straightforward. “It took making this whole film, the three years of production and a year of reflecting on it to come to these realisations. It was an overwhelming experience and I needed to get to the root of it… that is why it ended up as something that was kind of simple for people to understand. ”

Sameer tells me he took a similar approach when dealing with the subject of borders. “I decided not to look at borders in a political way, but rather in a personal one. I questioned how they are hindering my own personal growth and my ability to connect with other people,” he says. “That’s where I started to understand just how oppressive and comlex this situation is, as it’s not just political. It’s emotional.”

In Walled Citizen, we meet couples who are divided by state border restrictions and literally walled in due to lack of freedom of movement. In viewing the intimate emotions of those affected by occupation through film, the viewer can connect to common humanity and empathise with those who were born into political crisis. In watching Sameer’s film, Western viewers learn that human rights are not complicated at all, but simply rooted in a system of hegemony and white supremacy which values certain peoples as more deserving of basic rights.

Creativity as community healing

I ask Sameer about the intersection of his filmmaking experience and his identity as a Palestinian. “Filming is a kind of therapy for me,” he says. “I found the process of making the film, and drawing these conclusions, really helpful.” He continues; “Before Walled Citizen, I was really struggling. But I decided not to despair and instead to make a film in order to actually understand how to find freedom. The film helped me a lot, yaani, it changed my life.”

Join our mailing list

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Sign up for shado's picks of the week! Dropping in your inbox every Friday, we share news from inside shado + out, plus job listings, event recommendations and actions ✊

Walled Citizen is not the first film Sameer has made as a form of therapy. He tells me about a film he made during quarantine using family home video footage from his grandfather during the Second Intifada when he was a child. “I took advantage of the time in isolation to go back to that past in an attempt to reconcile how I felt about it. I made a film to heal from that trauma.”

The concept of trauma reconciliation through creativity resonated with me. I am a member of an immigrant family, belong to the Jewish community, and come from Tulsa, Oklahoma – a place devastated by the Tulsa Race Massacre and the final destination of the Native American Trail of Tears.

To reconcile trauma through art is to heal. Whether it be Sameer’s filmmaking, my writing as an Iranian American Jew in Palestine, or the growing music scene in Black Wall Street [the site of the Race Massacre], people connect and collaborate through art to heal. To create art is to be productive, and to be productive while healing with one’s community is to be fulfilled.

Sameer is currently working on a ten part web video series called ‘Beingless’, set to come out in mid-2023. In a similar vein to Walled Citizen, it will focus on the people of Palestine rather than the politics. “It will feature artists, dancers, entrepreneurs – people sharing their personal stories and hopes.” he explains. “It will look at what they are trying to accomplish in this life – regardless of the situation they’re in. Through relatable storytelling, I hope people can see us differently. Not as figures of war and death, but instead as people, full of beauty and hope.”

He concludes: “The more content we make that is relatable, the more we can draw attention to the world that we know… We are just like you. We are not born to die.”

What can you do?

- See: Walled Citizen by Sameer Qumsiyeh, Belonging by Sameer Qumsiyeh (upcoming)

- Hear: Fire in Little Africa, a hip hop album reconciling the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 from my hometown, Tulsa

- Read: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 13 on Freedom of Movement and Right of Return

- Act: Support your local arts and social justice movements

- Do: Call for humanity in Palestine!

- Find out more about movements for social justice in Palestine in the following articles